“The misfortune of others tastes like honey” is a Japanese saying that rings uncomfortably true. But why does it feel so accurate? Here are two reasons behind the experience of Schadenfreude.

getty

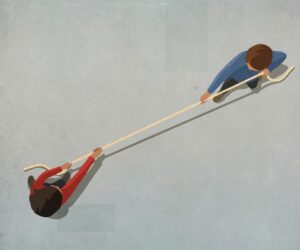

Most of us have a natural tendency to compare ourselves to others. This can be explained by social comparison theory, developed by psychologist Leon Festinger, which suggests that we determine our self-worth by comparing ourselves to others.

When others experience setbacks, we may experience a range of emotions in response, from empathy to pity to even joy at their misfortune. While feeling happy about someone else’s pain may sound strange, it’s not as uncommon as you might think. This stems from our tendency for “downward social comparison.”

When we compare downward — i.e., to someone worse off — we often feel better about our own lives. It’s a subtle, sometimes unconscious coping mechanism, especially in moments of self-doubt.

The emotional experience of pleasure in response to another’s misfortune is called Schadenfreude, a German word that combines Schaden, which means “damage,” and Freude, which means “joy.”

Schadenfreude often occurs in competitive environments. For instance, you may feel happy when an employee who cozies up to your boss performs poorly and gets berated by them.

This is because people have an inherent need to feel better about themselves and often acquire a better self-image by comparing themselves to others who may be less fortunate. Consequently, people who feel their self-worth is threatened are more likely to feel Schadenfreude.

Here are two key reasons why you may be feeling happy about somebody else’s suffering:

1. Schadenfreude May Boost Self-esteem In Competitive Scenarios

Why do we feel a sense of guilty pleasure at someone’s downfall? In a 2017 study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, researchers sought to answer this question.

They tested whether Schadenfreude met any of these four basic psychological needs: the need for self-esteem, control, belongingness and a meaningful existence. Researchers conducted four experiments, all of which pointed to similar outcomes: Schadenfreude does meet our basic need to reaffirm our social standing through comparisons, especially when we compare ourselves to a rival we’re envious of.

In the first study, participants were asked to imagine being in a job interview, which was also being attended by their primary university competitor. They were told that only one would get the position. In the competitive scenario, participants felt more schadenfreude and need satisfaction than in non-competitive circumstances.

Researchers found that they felt more in charge, experienced higher self-esteem and felt a greater sense of belonging. In another situation, they were asked to recall a real-time scenario when their competitor failed. Once again, researchers found that more schadenfreude led to increased feelings of self-esteem, a greater sense of personal control and a stronger perception of meaning in life.

Seeing someone else fail or struggle can shield us from feelings of inadequacy, at least for the time being. When life feels out of control, seeing others in similar or worse positions makes our own experiences feel less like personal failures and more like part of a shared human messiness. This is especially true in more competitive scenarios.

We all want to believe we’re doing “okay” in life. If someone else is doing worse than us, it affirms that we’re not falling behind.

2. Schadenfreude May Reaffirm Your Belief In A Just World

Interestingly, another 2013 study published in the Australian Journal of Psychology found a link between schadenfreude and beliefs in a “just” world. When people’s belief in a just world was threatened, they felt more pleasure when someone else suffered a misfortune. For example, they might laugh more at a story where someone “gets what they deserve.”

This may be because they want to restore their belief that the world is fair. When someone holds such beliefs, they’re more likely to think that good things happen to good people, while misfortune finds those who deserve it. If they can’t help the victim, they might instead blame the victim or believe the person deserved it. This way, they get to justify the misfortune that befell them.

However, this does not always indicate that the victim is deserving of punishment or that they are responsible for the outcome.

Does Schadenfreude Make You A Bad Person?

Schadenfreude doesn’t automatically make you a terrible human being. The practice of downward comparison may feel cruel, but that is not always the intention. These reactions often happen without our conscious awareness, and you may have tried to push these thoughts away, knowing it wasn’t right.

This sense of awareness and moral grounding is what differentiates you from someone that deliberately wants to watch others fail.

However, if you find yourself constantly hoping for someone else’s downfall and actively trying to put them in compromising situations, that may be worrisome.

Instead of trying to eliminate the instinct entirely, try to notice it but avoid giving it too much power. Otherwise, it may make you complacent and feel less motivated to improve because you think “at least, I’m not that bad.”

If you must compare, try to shift your mindset to lateral or upward comparisons that inspire change. Try to put in effort to grow. Look at people doing “better” than you and learn from them.

If seeing others do better than you makes you feel like you’re “not enough” or that you haven’t “achieved enough,” try comparing yourself to those only one or two steps ahead of you. That way, you can realistically map out your progress.

You may also want to mark your progress against your past self. Self-comparison allows you to see how far you’ve come and where you want to go from here, but like any form of comparison, it’s a double-edged sword that can make you spiral about your flaws.

The healthiest approach is to learn to accept yourself right where you are, without any sense of comparison, viewing your journey in this life as strictly your own. When you begin to embrace the feeling of being and having “enough,” you naturally stop engaging in self-destructive behaviors or trying to bring others down.

Do you often take pleasure in others’ misfortune to make yourself feel better? Take this science-backed test to find out: The Schadenfreude Scale