Christopher Columbus and other early European explorers were best known for the “new” lands they discovered and the people they transported. But there’s another side to the story, and it has to do with the flora they brought with them.

getty

When Christopher Columbus traveled to the Americas in the late 1400s, he inaugurated one of the most transformative ecological exchanges in human history. Particularly, his second expedition in 1493, equipped with seventeen ships and roughly a thousand men, was not just exploratory but made for the purpose of colonizing. Alongside the settlers and soldiers came a menagerie of plants and animals that aimed to recreate European life in the tropics.

This transoceanic movement of species — what biologists and historians now call the Columbian Exchange — reshaped the world’s ecosystems and economies alike. Much attention has been paid to the people and animals Columbus brought with him, but his plants were just as consequential. Many of the species he introduced took root, both literally and figuratively, across the Americas.

Here’s a closer look at some of the most important plant species brought by Columbus and his successors, according to records on the Columbian Exchange, and how they changed the ecology of the New World forever.

1. Bananas

A banana worker bicycyles through banana plantations in the early morning hours in Puerto Viejo de Sarapiqui in Costa Rica. The volcanic mountain range of the Cordillera Central provides a beautiful backdrop.

getty

Contrary to popular belief, bananas aren’t native to the Americas. However, by 1493, they had already reached the Canary Islands via Portuguese traders — before Columbus’s era. Columbus reportedly brought banana suckers on his second voyage, and they flourished in the humid Caribbean climate.

Within decades of European settlement, bananas had become a dietary staple across tropical America. They naturalized easily, and they formed dense stands that shaded out native vegetation. Today, their descendants are among the most widely cultivated crops in the Western Hemisphere.

2. Wheat

To the Europeans aboard Columbus’s second voyage, wheat was so much more than a mere crop. If anything, it was symbolic of civilization itself. Bread was one of the most central components of European diets and rituals. In this sense, settlement without wheat was, in their minds, incomplete.

Columbus introduced wheat seed to the Caribbean, but the tropical humidity quickly dashed hopes of a successful harvest. Years later, wheat would find its eventual footing in the Mexican highlands and Peruvian valleys, where the temperate climates favored it. The crop’s eventual establishment marked the beginning of the European-style agricultural grid: cleared forests, plowed fields and monocultures that displaced native vegetation.

3. Sugarcane

Long rows of sugar cane.

getty

If wheat symbolized civilization, sugarcane symbolized empire. It was originally domesticated in Southeast Asia, and, at this point, had already reached the Mediterranean. By the Middle Ages, it was already a profitable export from the Canary Islands when Columbus departed.

Columbus carried sugarcane cuttings on his second voyage and planted them in Hispaniola — known better today as Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Here, the combination of volcanic soils, abundant rainfall and forced labor proved devastatingly effective. By the early 1500s, the Caribbean had become the heart of a plantation system that reshaped global economies, but more so human societies.

Biologically, sugarcane cultivation transformed landscapes. With it, forests were replaced by vast plantations, runoff altered the nature of waterways and soil erosion increased dramatically. Ecologically, sugarcane was perhaps the plant that began the Caribbean plantation ecology that’s still highly visible today.

4. Citrus Fruits

Among the most successful introductions were citrus fruits: oranges, lemons and limes. Although these originated in Southeast Asia, they had long been cultivated around the Mediterranean.

Columbus brought citrus seeds and saplings to the Caribbean in 1493, where they found the tropical sun and well-drained soils ideal. Within just a few decades, modern-day Haiti, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and later Florida and Mexico were covered in various different kinds of citrus groves.

Notably, there were no native citrus species in the Americas; they were a completely foreign arrival. Yet economically, citrus has become a pillar of both tropical and subtropical agriculture.

Other Plants Brought By Early European Settlers

Columbus’s fleet carried seeds for what Europeans considered essential kitchen crops: onions, garlic, cabbages, lettuces and other greens. These were relatively minor players compared to sugarcane or bananas, but they still symbolized something much more pertinent: the colonizers’ need to recreate their home.

The Caribbean climate made their cultivation challenging, but in cooler highlands and coastal settlements, these species did eventually take root. They had no true counterparts in pre-Columbian agriculture, although wild relatives of onions and brassicas did exist. Their ecological footprint was relatively modest, but from a cultural standpoint, this marked the start of the Europeanization of American diets.

Melons, parsley, mint, oregano and basil rounded out the Columbian exchange’s horticultural cargo. Melons thrived in warm, dry areas, which led to indigenous farmers to quickly embrace them. Herbs were mostly confined to mission gardens and monastery plots, where friars cultivated them for food and medicine.

Though many of these seeds and crops failed to naturalize widely, they nevertheless aided in the establishment of small-scale horticultural systems that ultimately combined European and American crops. These are some of the earliest examples of agricultural hybridization in the New World.

However, it’s still worth remembering that, at the same time that Europe was exporting its agricultural staples westward, the Americas were also exporting their own. Maize, potatoes, tomatoes, cacao, chili peppers, tobacco and beans from the New World would return across the Atlantic to revolutionize Old World cuisines.

Still, in the context of Columbus’s voyages, it was the imported wheat, sugarcane, bananas and citrus that laid the foundation for the colonial economy. This, in turn, permanently altered the very ecology of both North and South America.

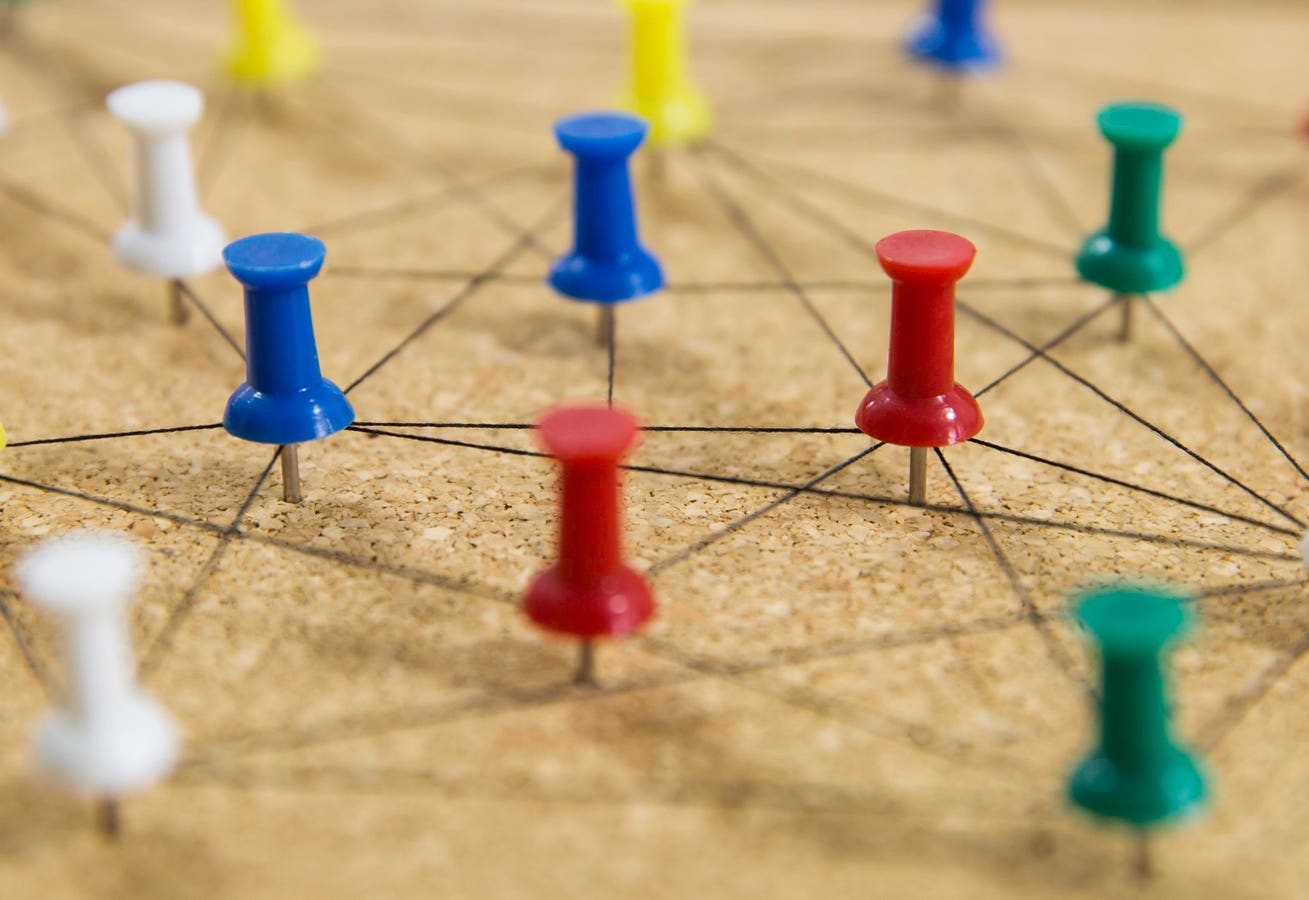

The Americas, long isolated since the breakup of Pangaea and the last Ice Age, were suddenly seeded with Eurasian species that were specifically adapted to entirely different climates and interactions. Some were lucky enough to flourish, while many others failed. But together, they initiated a biological homogenization: the blending of once-separate ecosystems into a single global web of species and commerce.

Does the idea of an “invasive species” instantly change your mood? Take the Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension.