“CITES Parties must act before these animals disappear from our oceans entirely.” – Luke Warwick, Director of WCS Shark & Ray Conservation

Anadolu via Getty Images

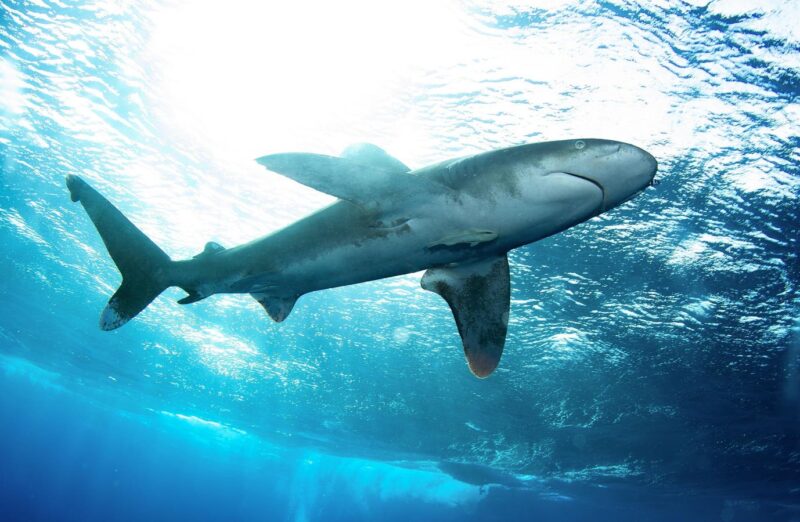

Sharks and rays are disappearing from our oceans faster than most of us realize. Over a third of all species are now threatened with extinction, and for those caught in international trade, the risk nearly doubles. Genetic testing in major shark markets shows a sobering truth: far more shark products are circulating than official records suggest. The illegal and unreported trade is pervasive, hiding in plain sight. Pelagic sharks in the open ocean have lost over 70% of their populations in just the past 50 years. Reef sharks are functionally extinct on one in five coral reefs worldwide.

And while, yes, these are numbers you are reading on a screen, they’re more than just that. They are actually the screams of ecosystems unraveling, but we’re so disconnected from it all they’re merely echos to those outside the conservation industry. The 20th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CITES, or CoP20, opens today in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, and the stakes could not be higher. More than 50 governments are co-sponsoring proposals to offer the strongest global protections for sharks and rays ever presented under the Convention. Among these, the oceanic whitetip shark (Carcharhinus longimanus), manta rays, devil rays, and whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are being considered for Appendix I status, effectively banning international trade. Wedgefish and giant guitarfish could see zero export quotas. Appendix II proposals would bring species like gulper sharks, smoothhound sharks, and tope sharks under closer monitoring and trade regulation. If adopted, nearly all fin trade and a majority of shark meat trade would come under CITES oversight.

Sharks and rays are not just charismatic ocean creatures that grace the Hollywood screen every year with a (bad) summer blockbuster; they are ecosystem engineers. Predatory sharks regulate the populations of other marine species, maintaining balance across reef and open ocean habitats, and rays stir the seafloor, cycling nutrients and supporting benthic communities. Remove either of these predators and the effects ripple outward, altering food webs, reducing biodiversity and even impacting fisheries that humans rely on. When a species like the whale shark disappears from a region, what other subtle changes follow in the ecosystem? How long before those changes affect the food on our own plates? The scientific consensus is, and has been, clear. We need sharks and rays to have healthy oceans. And, as Luke Warwick, Director of WCS Shark & Ray Conservation, says: these animals cannot withstand commercial trade. “The science is unequivocal, and the tools and support to implement CITES already exist for governments once listings pass. CITES Parties must act before these animals disappear from our oceans entirely,” he said in a press release e-mail. The tools to protect them exist! Genetic testing, identification guides, and enforcement resources are all readily available to (most) governments. The question now is whether the global community has the political will to act before these species vanish entirely.

Said Dr. Susan Lieberman, WCS Vice President of International Policy: “Recent science shows that we are quickly approaching a conservation tipping point for sharks and rays. We are running out of time to enact and enforce global measures that will prevent widespread extinctions.”

AFP via Getty Images

The proposed listings are also designed to harmonize with other international agreements. The Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals and several Regional Fisheries Management Organizations already prohibit the retention of many of these species. Bringing CITES into alignment with these frameworks will strengthen enforcement and close loopholes that allow illegal trade to flourish. Ultimately, these protections could mean the difference between survival and extinction. Yet even with protections in place, enforcement is only part of the solution. Trade regulations needs to be backed by monitoring at ports, markets, and borders. Illegal trade often moves faster than policy, slipping through gaps created by lack of funding, inadequate training, or corruption. Because of this, genetic tools (which can identify species from processed fins or meat) are becoming indispensable for enforcement. They can provide undeniable proof, but only if authorities use them consistently; this is where science directly informs action, translating lab results into policy decisions that affect real lives. “We are running out of time to enact and enforce global measures that will prevent widespread extinctions,” said Dr. Susan Lieberman, WCS Vice President of International Policy, who warns that we are approaching a conservation tipping point. “These proposed listings bring CITES in line with other global commitments and send a clear signal that the world intends to protect these amazing sharks and rays before it is too late. This is how we turn the tide.”

It is tempting to marvel at data, charts, and statistics. Yet the story of sharks and rays that is currently unraveling is one of global responsibility and ethical choice. The moment to act is now. Waiting even a few years could mean passing the point where protections can reverse declines. This meeting of the minds is a global opportunity to prevent extinctions that would otherwise be inevitable. What does it mean if we allow these iconic species to vanish while solutions exist? How do we measure the cost of their disappearance beyond economics — through the lens of lost ecological function, cultural significance, and human curiosity about the ocean? These questions should linger in every discussion being had about their conservation, reminding those in charge that science is inseparable from the choices societies make.

Yes, the proposals before CITES this month are ambitious, but ambition is necessary. Sharks and rays have existed for hundreds of millions of years, yet today, they face a threat entirely of our making. The momentum is there: governments co-sponsor listings, science provides guidance, and enforcement tools are ready. What remains is action, a coordinated effort to ensure that the oceans retain their predators and engineers. If CoP20 succeeds, it may mark a turning point in global marine conservation. If it fails… the oceans will be quieter, emptier, and poorer in ways that will ripple far beyond our shorelines.