The ostrich is the tallest bird that inhabits the planet today, but fossil evidence suggests that … More

When you think of birds, your mind immediately goes to the sky.

But not all birds fly.

Consider the emperor penguin. Scientists estimate that emperor penguins lost their ability to fly about 60 million years ago. The reason is straightforward: evolution pushed them in the direction of becoming sleek swimmers instead of aerial maneuverers.

The process of evolution caused many birds to trade flight for a different physique – one that was better optimized to meet the challenges of their environment. The ostrich, for instance, traded its ability to fly for a bigger size (yes, flight becomes more challenging the heavier a species becomes). This evolutionary pathway produced a large, ground-dwelling species well-adapted to the open landscapes of the African plains.

And, what the ostrich gave up in terms of flight speed, it got back by becoming a long-legged, fast runner (ostriches have been known to run at speeds of up to 40 miles per hour).

Often, when birds give up their ability to fly, it is for one of these two reasons – either to become better swimmers, as in the case of emperor penguins, or to increase their size, as with the ostrich. So, when searching for the largest bird of all time, it makes sense to look in the realm of flightless birds.

And that is exactly where we find our winner: the South Island giant moa of New Zealand. Here is its evolutionary story, from genesis to extinction.

South Island Giant Moa – Earth’s Tallest Bird Explained

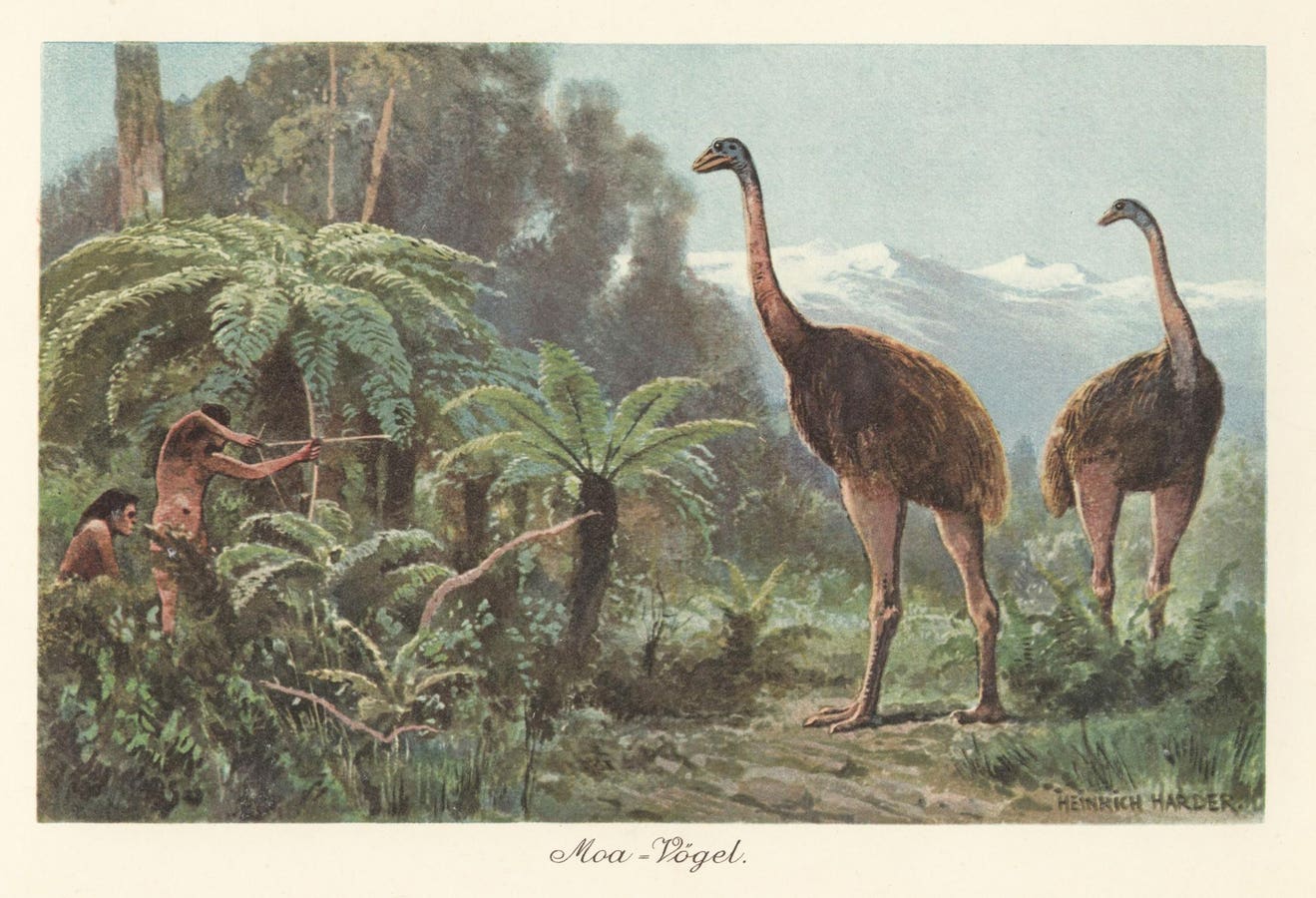

Although many flightless birds have emerged across the globe at different times in our evolutionary past, few rival the South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus) in sheer scale. Towering at up to 12-13 feet tall when stretching its long neck upright, and weighing as much as 600 pounds, this massive, herbivorous bird dominated the forest floors of New Zealand until its extinction around 1450 A.D.

Unlike ostriches or emus, which still have visible wings (albeit useless for flight), the moa was entirely wingless – lacking even the vestigial bones that typically hint at avian ancestors’ flying past. This makes the moa one of the only known birds to have evolved into a truly wingless form.

In the absence of native land mammals, many of New Zealand’s birds — like the moa and kiwi pictured … More

The moa’s evolutionary journey began tens of millions of years ago, when its ancestors arrived in New Zealand, likely by flying or rafting over when the landmass was still closer to other southern continents. Once isolated, the birds faced a unique environment: New Zealand had no native land mammals (except for a few species of bats), which allowed birds to fill ecological roles typically occupied by ground-dwelling mammals in other parts of the world.

In the absence of large predators, size became an advantage, not a liability.

Over time, some moa species evolved into true giants. The South Island giant moa roamed grasslands and forested valleys, grazing on tough plant material such as ferns, shrubs, and leaves from high branches – reaching food sources that few other animals could. Its long legs and flexible neck gave it the ability to browse at multiple heights, not unlike a modern giraffe.

The only known predator of adult moa was the Haast’s eagle, another New Zealand native and the largest eagle species ever known. Even so, adult moas were difficult to bring down.

It was only when humans arrived – specifically, the Māori people around the late 13th century – that the fate of the giant moa was sealed. With no fear of humans and no evolutionary defenses against hunting, moa populations quickly declined under intense pressure from overhunting and habitat destruction. Within just a couple of centuries of human arrival, the South Island giant moa, along with all nine species of moa, was gone.

(Sidebar: As tragic as our role was in driving the giant moa to extinction, perhaps the most lamentable form of human-caused extinction is when species are hunted into oblivion for the sake of fashion — see here to learn how this trend ties into the most valuable package lost aboard the Titanic.)

What makes the moa particularly fascinating is not just its size, but its stark deviation from what we typically think of as “bird-like” traits. It couldn’t fly, it didn’t have wings, and it occupied a role in the ecosystem more akin to a browsing mammal than a feathered flyer. In many ways, the moa was more like a feathered dinosaur than a modern bird – an evolutionary echo of ancient times.

Today, the legacy of the giant moa endures through its fossilized bones and the stories preserved in Māori oral tradition.

Does thinking about the extinction of a species instantly change your mood? Take the Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension.