The fictional fear sparked by Jaws triggered decades of real-world harm, but today’s science and … More

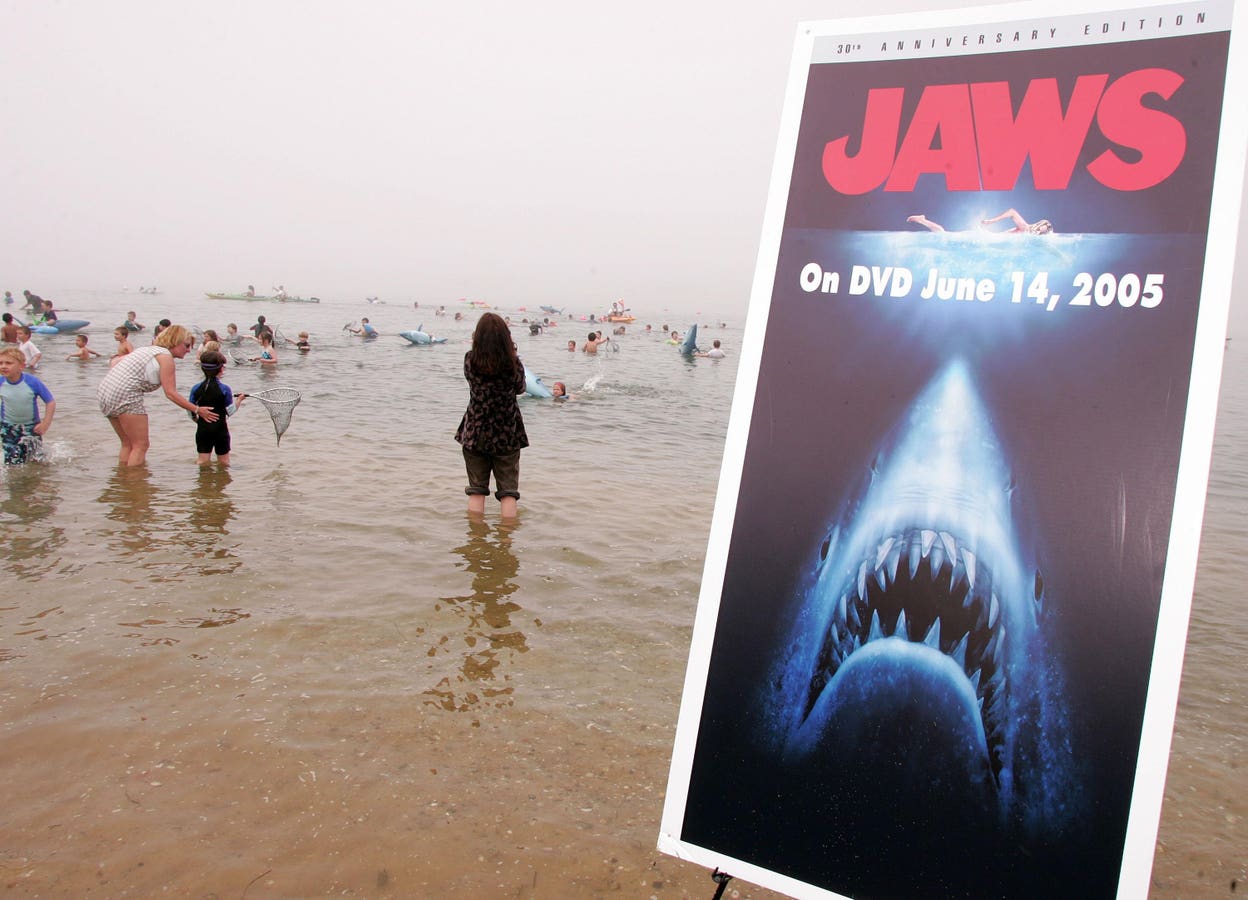

In 1975, a mechanical great white shark terrorized beachgoers on the big screen in Jaws, launching a cultural phenomenon and an ecological crisis. The film raked in what would today equal nearly $2.7 billion and left a legacy of fear that fueled shark culls, trophy hunts, and policies rooted more in panic than science. That legacy is still felt in the water and in the public imagination. But in the decades since, researchers, filmmakers, and conservationists have worked tirelessly to change the story. They’ve had to counteract a narrative etched into pop culture with something far more nuanced and urgent: sharks are not villains. Instead, they are vital ocean predators facing serious threats. And instead of being hunted, they should be protected, because they’re worth more alive than dead.

The damage done by Jaws went beyond the silver screen. It gave sharks a brand problem. The irrational fear it sparked led to government-sanctioned culling programs, beach net installations, and recreational killing. Some species were pushed to the brink, their populations collapsing under the weight of fear-driven policy and overfishing. But as scientific understanding of sharks improved and marine ecosystems were better studied, the narrative began to shift. People started to realize that removing apex predators from the ocean had ripple effects throughout entire ecosystems. Coral reefs suffered, fish populations became unbalanced, and the ocean’s health declined.

Enter science communication and eco-tourism. A new generation of researchers, often appearing on platforms like Shark Fest, Shark Week or in nature documentaries like Blue Planet, began to reframe sharks not as mindless killers but as essential, often misunderstood animals. Tracking programs tagged great whites, hammerheads, and tiger sharks, producing maps that let the public follow their migrations in near real-time. This gave people a new way to connect with the animals and social media accounts connected to these individual sharks amplified the movements of these animals, demystifying the species while humanizing the work one sassy update at a time.

Visitors wear shark-shaped hats, inspired by Steven Spielberg’s film series “Jaws,” at Universal … More

At the same time, a global shark tourism industry began to grow. Today, shark tourism generates around $314 million annually and supports more than 10,000 jobs. In places like Australia, the Bahamas, Fiji, and South Africa, shark diving has become a major draw, bringing in revenue that helps fund local conservation efforts and research. Some communities that once relied on fishing sharks now make more money keeping them alive and inviting tourists to swim alongside them. It’s a powerful economic argument — that a live shark can be worth far more than a dead one — that conservationists have used to shift attitudes. But changing public perception hasn’t been easy, especially when a blockbuster like Jaws has left such a long cultural shadow to get out of. However, it seems like consistent messaging and education, especially when tied to real-world experiences, have begun to work. Conservation groups like The Shark Trust and The Atlantic White Shark Conservancy receive millions of dollars in donations and grants to study and protect sharks. Recent campaigns from non-novernmental grganizations and initiatives have focused on science-backed policy changes (such as creating marine protected areas) and free educational outreach content (as seen here by the Australian Marine Conservation Society). Citizen science efforts have also played a role, with divers around the world logging sightings, tagging programs opening to the public to raise money for science, and apps that let anyone contribute to data collection — all of which have helped foster a sense of shared responsibility for the future of these animals.

Still, the contrast between the economic success of Jaws and the current push for shark conservation is stark. Jaws made about $470 million at the box office back in the 70s, which when adjusted for inflation is a few billion dollars. That single film’s reach is hard to compete with. But what instead of competing to make all people everywhere not afraid of sharks, a replacement narrative was offered. One that says sharks are complex, diverse, and vulnerable. That humans are far more dangerous to sharks than the other way around. And that the health of our oceans depends on their survival.

That’s exactly what conservationists have done, and it seems to be working.

It’s fitting that 50 years after Jaws hit theaters, some of the very beaches that once feared shark sightings now advertise them. Shark festivals celebrate them. Dive operators depend on them. And schoolchildren are taught about their ecological importance, not their supposed bloodthirst. It is not a perfect recovery, as many shark species are still in danger from climate change, habitat destruction, and bycatch, but it’s a striking transformation to what once was. The road to repairing sharks’ reputations has been long and full of obstacles, and in many ways, it’s a blueprint for how we might reframe other misunderstood or maligned species. That’s the real plot twist.