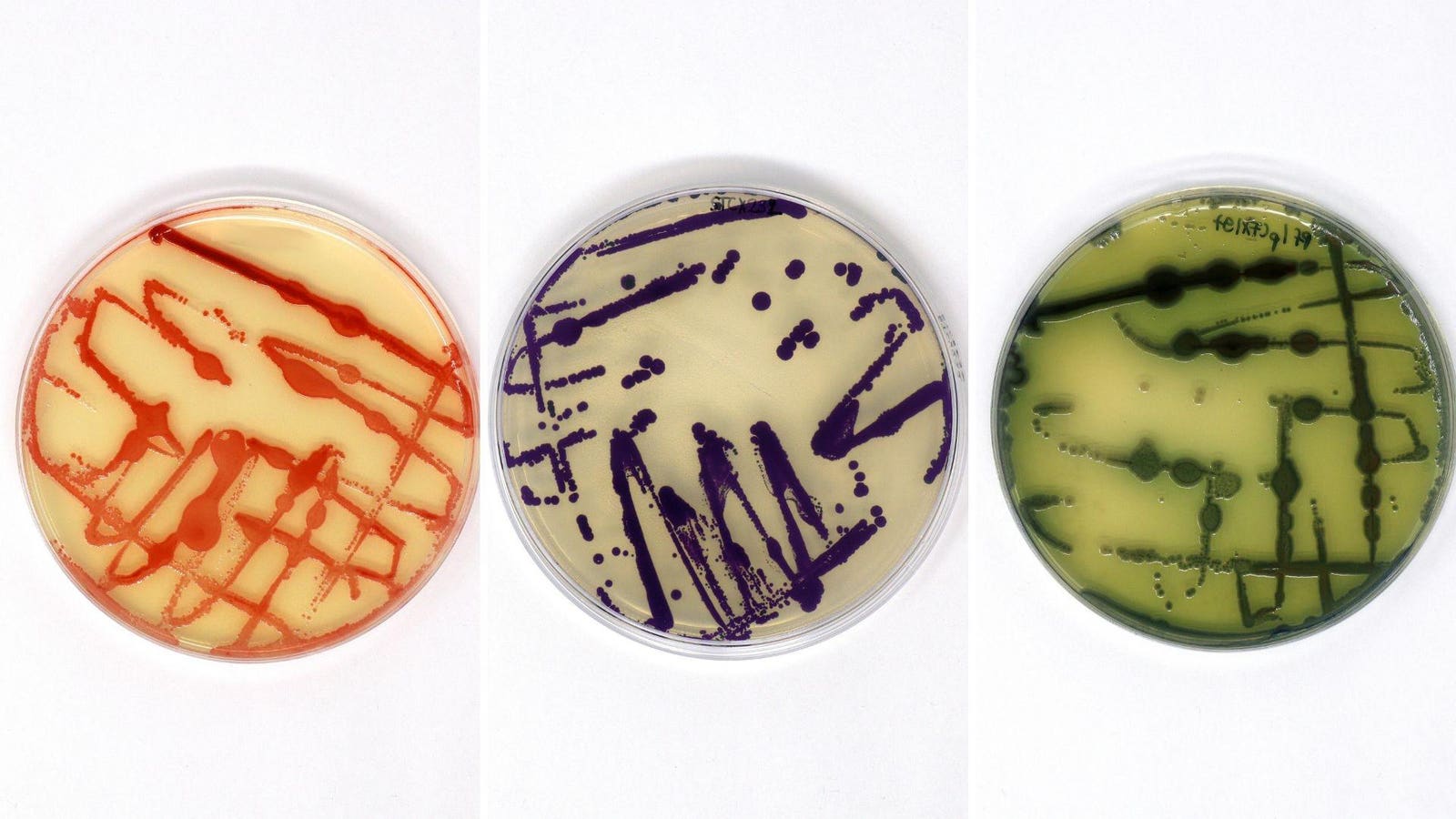

Three different microbial pigments

What comes to mind first when you think about the environmental cost of what we wear every day?

Fossil-fuel fabrics, overflowing landfills and underpaid labour are often front and centre of the conversation, and rightly so.

But what rarely makes it into the headlines – is dye – the stuff that makes our clothes colourful.

Fashion’s dirty secret

Textile dyeing is actually one of the most chemically intensive and polluting elements of garment production, accounting for roughly 20% of global industrial water pollution.

The vast majority of dyes in use today are made from petrochemicals, derived from crude oil. And the amount of water required in the process is staggering.

A single pair of blue denim jeans can take up to 7,000 litres of water to produce. Plus, the indigo hue is synthetic and involves toxic chemicals and heavy metals in its manufacturing.

Garment workers in a synthetic, indigo dyeing pool for blue denim jeans.

In factories all over the world, from China to Bangladesh, these pollutants are dumped untreated into rivers, poisoning ecosystems and endangering communities.

It’s a problem that sits in plain sight, literally on our backs, yet remains largely missing from the sustainable fashion discourse.

Disrupting the industry

Synthetic dyes are cheap, efficient and industrially embedded. They provide a wide colour spectrum, which brands like, and deliver predictable results – perhaps why no viable solution has been able to compete.

Natural dyes made out of plants have been used for centuries, but their problem? The colours tend to be earthy and dull and, crucially, don’t stick to the fabric and eventually fade.

One British breakthrough may have solved the problem, by inventing a ‘green’ dye (not literally) that meets the industry’s rigorous expectations. It’s scaleable – and that means there is potential to disrupt the status quo.

Instead of mining oil or boiling vats of chemicals, Colorifix uses engineered microorganisms, (essentially programmable microbes) to grow colours in the lab. Fed with sugar and salt to create a specific pigment, these microbes act like miniature factories, brewing vibrant dyes that are transferred directly onto fabric using a fraction of the water and none of the toxic additives.

Fed with sugar and salt to create a specific pigment, the microbes act like miniature factories, brewing vibrant dyes.

Live bacteria in a petridish, which creates natural pigment for sustainable dye.

The idea first emerged from a very different kind of lab, out in nature. In 2012, two University of Cambridge researchers were studying polluted drinking water in rural Nepal. They used bacteria to detect contaminants in water, which had been engineered to change colour in the presence of specific chemicals – a simple, visual indicator for unsafe water.

But as they spoke with local communities about the root causes, the answer kept circling back to the same culprit: textile dye.

So instead of building tools to detect pollution, they pivoted to tackling the source of it directly, by using DNA sequencing found in our natural world. Say, the genetic code for blue in a butterfly wing, or the pink of a flower petal.

By using DNA sequencing, they can copy the genetic code for a blue butterfly wing.

Using DNA sequencing found in nature, scientists can copy the genetic code for the blue in a … More

“Synthetic dyes are very well studied and substantiated in the textiles industry – but we’re doing our own analysis from scratch,” explains co-founder Jim Ajioka. “Growing the microorganism is a natural process, but we have modified it, to make the colours of other living organisms.”

“We get inspiration from nature – rather than extracting from nature,” says the other co-founder Orr Yarkoni.

A royal stamp of approval

Their approach is so radical that it has been recognised royally in the UK.

Colorifix became a finalist for the Earthshot Prize in 2023, a yearly contest led by Prince William to find the world’s most promising environmental solutions. The Prize is often said to have been inspired by JFK’s “Moonshot” and was designed to incentivise tipping-point innovations.

It has five categories, nature protection, clean air, oceans, climate and the one Colorifix competed in, waste-free solutions. Finalists receive mentorship and access to a network of global businesses, investors, and environmental organisations ready to help scale their ideas.

The Prince visited the lab this week to praise founders Yarkoni and Ajioka on their science-led approach. “It’s really exciting and I know you’re going to push into the industry very quickly,” he told the team.

“It’s really exciting and I know you’re going to push into the industry very quickly.”

Prince William visits Earthshot Prize Finalist, Colorifix, at their lab in Norwich, UK.

From biotech to big business

The microbial dye solution is already moving beyond the lab. In the last few years, it has received significant funding from highstreet brand H&M (here’s a t-shirt dyed by Colorifix). H&M’s innovation arm has invested in pilot dyeing projects in Portugal, where the startup’s biologically grown pigments were used on items produced for both H&M and Pangaia.

This marked one of the first real-world commercial applications of the technology.

Today, Colorifix has just closed a $18 million Series B2 round, led by Inter IKEA Group, to fuel global commercial expansion.

“This investment marks a critical milestone as we shift from proving our technology to delivering it at industrial scale,” Yarkoni tells me.

Colorifix has just closed a $18 million investment from IKEA to fuel global commercial expansion.

Linn Clabburn from IKEA’s innovation arm agrees. “Colorifix is addressing one of the toughest sustainability challenges in textiles,” she says. Their progress in scaling this tech and entering new markets “aligns well” with IKEA’s ambitions to improve sustainability in the value chain, she adds.

It’s a vote of confidence not just in the science, but in the market’s readiness for a pioneering solution.

Actress Nomzamo Mbatha in a dress dyed by Colorifix.

Unlike other sustainable alternatives that require entire factories to be revamped, Colorifix’s process is essentially plug-and-play and compatible with existing industrial dyeing equipment.

That means factories don’t need to overhaul infrastructure to adopt it, which removes one of the biggest barriers to sustainable innovation: cost and complexity.

The potential ripple effect is huge. If Colorifix can roll out its microbial dyeing process across fashion and homeware with some of the biggest household names, it could help detoxify one of the most water and chemical-intensive elements of garment production.

Easier said than done?

Transforming a $2 trillion-dollar supply chain does not come without its challenges. Colorifix’s technology may be simple to implement, but scaling it globally means convincing the big names this is the right idea for them, never mind navigating strict regulatory frameworks.

Textile manufacturers, often operating on razor-thin margins, can be slow to adopt new methods – especially in regions where environmental protocols are lax and synthetic dyes remain cheap and abundant.

Yet, momentum is building. Colorifix is already working with mills in Portugal, India and Brazil, with plans to expand into Southeast Asia, one of the largest dyeing hubs in the world.

“We are sure to make a difference.”

And the prospects don’t stop at fabric. The founders say their microbial process could one day be adapted for other industries like cosmetics and hair dye.

When Prince William comes to visit a project like this, he isn’t just there to tick a box. The Earthshot Prize was clearly designed to elevate this kind of bold, science-based solution with the power to transform entire systems. In fashion, that means anywhere we use colour, microbes could one day replace petrochemicals.

“Over the last few years, we have gone from grammes to tonnes of fabric per week,” says Yarkoni. “We are sure to make a difference.”