Why AI Illiterate Directors Are The New Liability For Boards Today

Twenty-three years after Sarbanes-Oxley mandated financial experts on audit committees, boards face an even more transformative moment. But unlike the post-Enron era when adding one qualified financial expert sufficed, the AI revolution demands something far more radical: every director must become AI literate, or risk becoming a liability in the intelligence age.

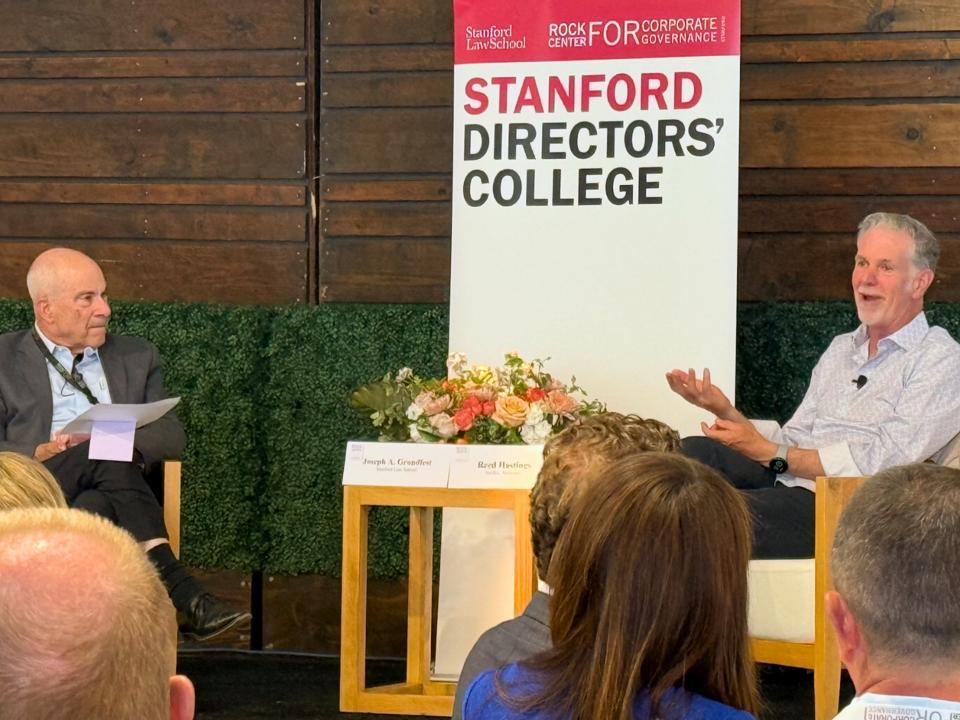

I just came back for the Stanford Directors’ College, the premier executive education program for directors and senior executives of publicly traded firms. Now in its thirtieth year, this year’s speakers included Reed Hastings, (Chairman, Co-Founder & Former CEO, Netflix; Director, Anthropic), Michael Sentonas (President, Crowdstrike), Maggie Wilderotter (Chairman, Docusign; Director, Costco, Fortinet and Sana Biotechnology), John Donahoe (Former CEO, Nike, ServiceNow, and eBay; Former Chairman, PayPal) and Condoleezza Rice (Director, Hoover Institution; Former U.S. Secretary of State). Organized by Stanford Law Professor Joseph Grundfest and the Co-Executive Director of Stanford’s Rock Center for Corporate Governance Amanda Packel, the program addresses a broad range of problems that confront modern boards. The topics are extensive, including the board’s role in setting business strategy, CEO and board succession, crisis management, techniques for controlling legal liability, challenges posed by activist investors, boardroom dynamics, international trade issues, the global economy, and cybersecurity threats. However, the topic that everyone wanted to discuss was AI.

Joseph A. Grundfest, (Co-Director, Stanford Directors’ College; W.A. Franke Professor of Law and … More

The stakes couldn’t be higher. While traditional boards debate AI risks in quarterly meetings, a new breed of AI-first competitors operates at algorithmic speed. Consider Cursor, which reached $500 million in annual recurring revenue with just 60 employees, or Cognition Labs, valued at $4 billion with only 10 people. These aren’t just “unicorns”, they’re the harbingers of a fundamental shift in how AI-first businesses operate.

The Sarbanes-Oxley parallel that boards are missing

After Enron’s collapse, the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) act required boards to include at least one “qualified financial expert” who understood GAAP, financial statements, and internal controls. Companies either complied or publicly explained why they lacked such expertise—a powerful mechanism that transformed board composition within five years.

Today’s AI challenge dwarfs that financial literacy mandate. Unlike accounting expertise that could be compartmentalized to audit committees, AI permeates every business function. When algorithms make thousands of decisions daily across marketing, operations, HR, and customer service, delegating oversight to a single “tech expert” becomes not just inadequate but dangerous.

The data reveals a governance crisis in motion. According to ISS analysis, only 31% of S&P 500 companies disclosed any board oversight of AI in 2024 and a mere 11% reported explicit full board or committee oversight. This despite an 84% year-over-year increase in such disclosures, suggesting boards are scrambling to catch up.

Investors are tracking (and targeting) AI governance gaps

Institutional investors have moved from encouragement to enforcement. BlackRock’s 2025 proxy voting guidelines emphasize board composition must reflect necessary “experiences, perspectives, and skillsets,” with explicit warnings about voting against directors at companies that are “outliers compared to market norms.” Vanguard and State Street have issued similar guidance, while Glass Lewis added a new AI governance section to its 2025 policies.

Large institutional investors, such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street, have varying policies … More

The enforcement mechanism? Universal proxy cards, mandatory since September 2022, enable surgical strikes against individual directors. Activists launched 243 campaigns in 2024 (the highest total since 2018’s record of 249 campaigns), with technology sector campaigns up 15.9% year-over-year. Boards with “skills gaps related to areas where the company is underperforming” face the highest vulnerability – and nothing screams skills gap louder than AI illiteracy while competitors automate core functions.

Consider what happened in 2024: 27 CEOs resigned due to activist pressure, up from 24 in 2023 and well above the four-year average of 16. The percentage of S&P 500 CEO resignations linked to activist activity has tripled since 2020. The message is clear: governance failures have consequences, and AI governance represents the next frontier for activist campaigns.

The existential threat boards aren’t seeing

Here’s the scenario keeping forward-thinking directors awake: while your board debates whether to form an AI committee, a three-person startup with 100+ AI agents is systematically capturing your market share. This isn’t hyperbole.

In legal services, AI achieves 100x productivity gains, reducing document review from 16 hours to 3-4 minutes. Harvey AI raised $300 million at a $3 billion valuation, while Crosby promises contract review in under an hour. In software development, companies report 60% faster cycle times and 50% fewer production errors. Salesforce aims to deploy one billion AI agents within 12 months, with each agent costing $2 per conversation versus human customer service representatives.

The economics are devastating for traditional business models. AI-first companies operate with 80-95% lower operational costs while achieving comparable or superior output. They reach $100 million in annual recurring revenue in 12-18 months versus the traditional 5-10 years. When Cursor generates nearly a billion lines of working code daily, traditional software companies’ armies of developers become competitive liabilities, not assets.

Why traditional IT governance fails for AI

Boards accustomed to delegating technology oversight to CIOs or audit committees face a rude awakening. Traditional IT governance focuses on infrastructure, cybersecurity, and compliance (the “what” of technology management). AI governance requires understanding the “should” – whether AI capabilities should be deployed, how they impact stakeholders, and what ethical boundaries must be maintained.

The fundamental difference: IT systems follow rules; AI systems learn and evolve. When Microsoft’s Tay chatbot learned toxic behavior from social media in 2016, it wasn’t a coding error, it was a governance failure. When COMPAS sentencing software showed racial bias, it wasn’t a bug but rather inadequate board oversight of algorithmic decision-making.

Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI research confirms that AI governance can’t be delegated like financial oversight. AI creates “network effects” where individual algorithms interact unpredictably. Traditional governance assumes isolated systems; AI governance must address systemic risks from interconnected algorithms making real-time decisions across the enterprise.

The coming wave of Qualified Technology Experts

Just as SOX created demand for Qualified Financial Experts (QFEs), the AI revolution is spawning a new designation: Qualified Technology Experts (QTEs). The market dynamics favor early movers. Spencer Stuart’s 2024 Board Index shows 16% of new S&P 500 independent directors brought digital/technology transformation expertise versus only 8% with traditional P&L leadership. The scarcity is acute: requiring both technology expertise and prior board experience creates a severe talent shortage.

This presents both risk and opportunity. For incumbent directors, AI illiteracy becomes a liability targetable by activists. For business-savvy technology leaders or tech-savvy business leaders, board service offers unprecedented opportunities. As one search consultant noted, “Technology roles offer pathways for underrepresented groups to join boards” – diversity through capability rather than tokenism.

The regulatory tsunami building momentum

The SEC has elevated AI to a top 2025 examination priority, with enforcement actions against companies making false AI claims. Former SEC Chair Gary Gentler’s warning that “false claims about AI hurt investors and undermine market integrity” was just the beginning about concerns about the rise of “AI washing,” or exaggerating and misrepresenting the use of AI. The Commission sent comments to 56 companies regarding AI disclosures, with 61% requesting clarification on AI usage and risks.

The SEC is increasing concerned about “AI washing” and AI disclosures

Internationally, the EU AI Act establishes the world’s first comprehensive AI regulatory framework, with board-level accountability requirements taking effect through 2026. Like GDPR, its extraterritorial reach affects global companies. Hong Kong’s Monetary Authority already requires board accountability for AI-driven decisions, while New York’s Department of Financial Services mandates AI risk oversight for insurance companies.

The pattern is unmistakable: just as Enron triggered SOX, AI governance failures will trigger mandatory expertise requirements. The only question is whether boards act proactively or wait for the next scandal to force their hand.

The board education imperative: From nice-to-have to survival skill

The data reveals a dangerous disconnect. While nearly 70% of directors trust management’s AI execution skills, only 50% feel adequately informed about AI-related risks. Worse, almost 50% of boards haven’t discussed AI in the past year despite mounting stakeholder pressure.

While many academic institutions and trade orgs are trying to fill this need, these traditional director education models (including annual conferences and occasional briefings) can’t match the exponential speed of AI’s evolution. Boards need continuous learning mechanisms, regular AI strategy sessions, and direct access to expertise.

The choice: Lead the transformation or become its casualty

The parallels to Sarbanes-Oxley are instructive but incomplete. Financial literacy requirements responded to past failures; AI literacy requirements must anticipate future transformation. When three-person startups with AI agent swarms can outcompete thousand-employee corporations, traditional governance models aren’t ready for these existential threats.

The window for proactive adaptation is closing rapidly. ISS tracks AI governance. Institutional investors demand it. Activists target its absence. Regulators prepare mandates. Most critically, AI-native competitors exploit governance gaps with algorithmic efficiency.

For boards, the choice is stark: develop AI literacy now while you can shape your approach, or scramble to catch up after activists, regulators, or competitors force your hand. In the post-Enron era, boards asked, “Do we have a qualified financial expert?” In the AI era, the question becomes, “Is every director AI literate?”

The answer will determine not just governance quality but corporate survival. Because in a world where algorithms drive business, directors who can’t govern AI can’t govern at all.