Once the MIT Museum was a sanctuary of substance, a sanctuary of wire and grit, a tribute to the restless engineering minds that reshaped the modern world. It didn’t rely on digital glitz to impress. It relied on the weight of history and the power of real machines. At its former location on Massachusetts Avenue, you could stand in the presence of a Lisp Machine, touch the echo of Norbert Wiener’s cybernetic dreams, and walk alongside the skeleton of Whirlwind, a machine that helped give birth to real-time computing and modern command systems. There was reverence in that cluttered space. Reverence for what mattered.

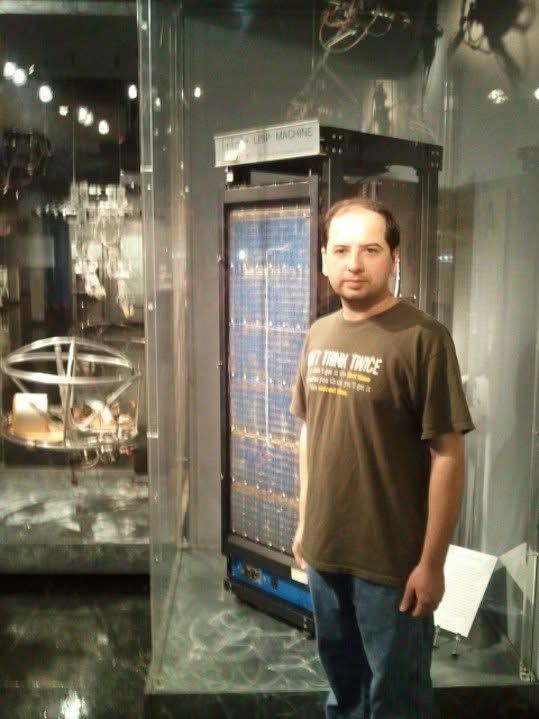

The author happily poses with a LISP machine during his visit to the old MIT Museum circa 2011. This … More

Today the museum sits in a bright glass structure at 314 Main Street in Kendall Square, reopened in October 2022 with architecture so clean and open it could house a Tesla showroom. And in many ways, that’s what it feels like: a showroom, not a museum. What was once dense, lived-in, and rich with context is now sterile, minimal, and vague.

The Lisp Machine is gone. No mention. No reverberation of its significance as a foundational platform for symbolic AI and hardware-software co-design. The machine that powered early explorations of logic, recursion, and reasoning is gone.

The Whirlwind computer, which once occupied an entire gallery and offered a visceral connection to the dawn of interactive computing, has been shrunk to a token display. There is little sense of what it meant, or how it led to the SAGE system and the concept of real-time control. Norbert Wiener, who coined the very term “cybernetics” and pioneered feedback theory, now appears fleetingly, as a cameo in a storyline that barely stops to acknowledge him.

Worse still, entire foundational episodes of MIT’s computing legacy are simply missing. There is nothing of Project Athena, which birthed the X Window System and laid the groundwork for distributed computing environments used by millions of Unix and Linux machines today. There is no exhibit on Sketchpad, Ivan Sutherland’s invention at MIT’s Lincoln Lab that introduced CAD, object-oriented programming, and graphical UIs in one stroke. No Multics. No Project MAC. No Mach kernel. No Athena terminals. No mention of the early Internet research that pulsed through MIT’s veins long before “web” meant anything beyond silk.

And perhaps most galling of all, there is no visible homage to one of MIT’s most important intellectual ancestors: Vannevar Bush, former MIT dean and wartime science advisor whose 1945 essay “As We May Think” introduced the world to the concept of the Memex. The Memex was the prophetic prototype of hypertext, personal knowledge augmentation, and linked information systems. It directly inspired Douglas Engelbart, J. C. R. Licklider, and ultimately the Internet itself. To walk through an MIT museum and find no trace of Bush’s vision is to suffer a kind of amnesia. It is to forget that the very architecture of digital thought began right here.

Wiener’s letters, DEC computers, Cog the Robot, Minsky’s work… all now finished or gone. The author … More

There is no CAD, no Ethernet, no Apollo software, no Negroponte. There is no tribute to Bob Metcalfe, who studied here before giving the world Ethernet. Nothing on Digital Equipment Corporation, whose PDP and VAX systems powered the birth of minicomputing right outside Boston. Nothing on Nicholas Negroponte’s Media Lab or the era when MIT commanded the world’s attention with its speculative, radical, and sometimes prophetic visions of a digital future. Nothing on the Fab Lab. Nothing on how Boston was the place where Apollo got its brain, where computing left the lab and entered life.

The new museum seems almost allergic to technical specificity. It favors safe abstractions, interactive video walls, and airy open space over crowded ideas. The exhibits don’t challenge. They don’t demand that you ask, What is this machine? How did it work? Who built it, and why? Instead, they offer mood boards and phrases like “impact,” floating in the air, unmoored from the harsh beauty of hardware.

And this is not just a curatorial misstep. It is a cultural shift. It reflects the broader decline in the soul of tech itself. From invention to branding. From engineering to aesthetics. From silicon and solder to slogans and slides. The MIT Museum could have been a temple to the raw engineering ethos that built everything we now take for granted. Instead, it has chosen to play it safe. To be tasteful, abstract, sanitized. A museum with no memory.

This matters. Because museums are not just rooms with things in them. They are arguments about what we value. They are stories about what we want to remember. MIT should remember its story. It should remember that what it gave the world was not just “innovation” but invention. Not just entrepreneurs, but engineers. Not just funding rounds, but revolutions in thought. If we forget that, if we allow even MIT to forget that, then we lose more than a museum. We lose the thread of how the world was built.

It is not too late to fix this. The archives are still there. The artifacts are still there. But someone must care enough to bring them back. To dust off the Lisp Machines. To roll Whirlwind back into the light. To honor Wiener, Bush, Sutherland, Metcalfe, and all the others not with a digital kiosk, but with the actual work. Until then, the MIT Museum will remain a beautiful shell with very little inside. A betrayal of MIT’s own legacy, and a cautionary tale of what happens when even the greatest institutions fall for their own marketing.