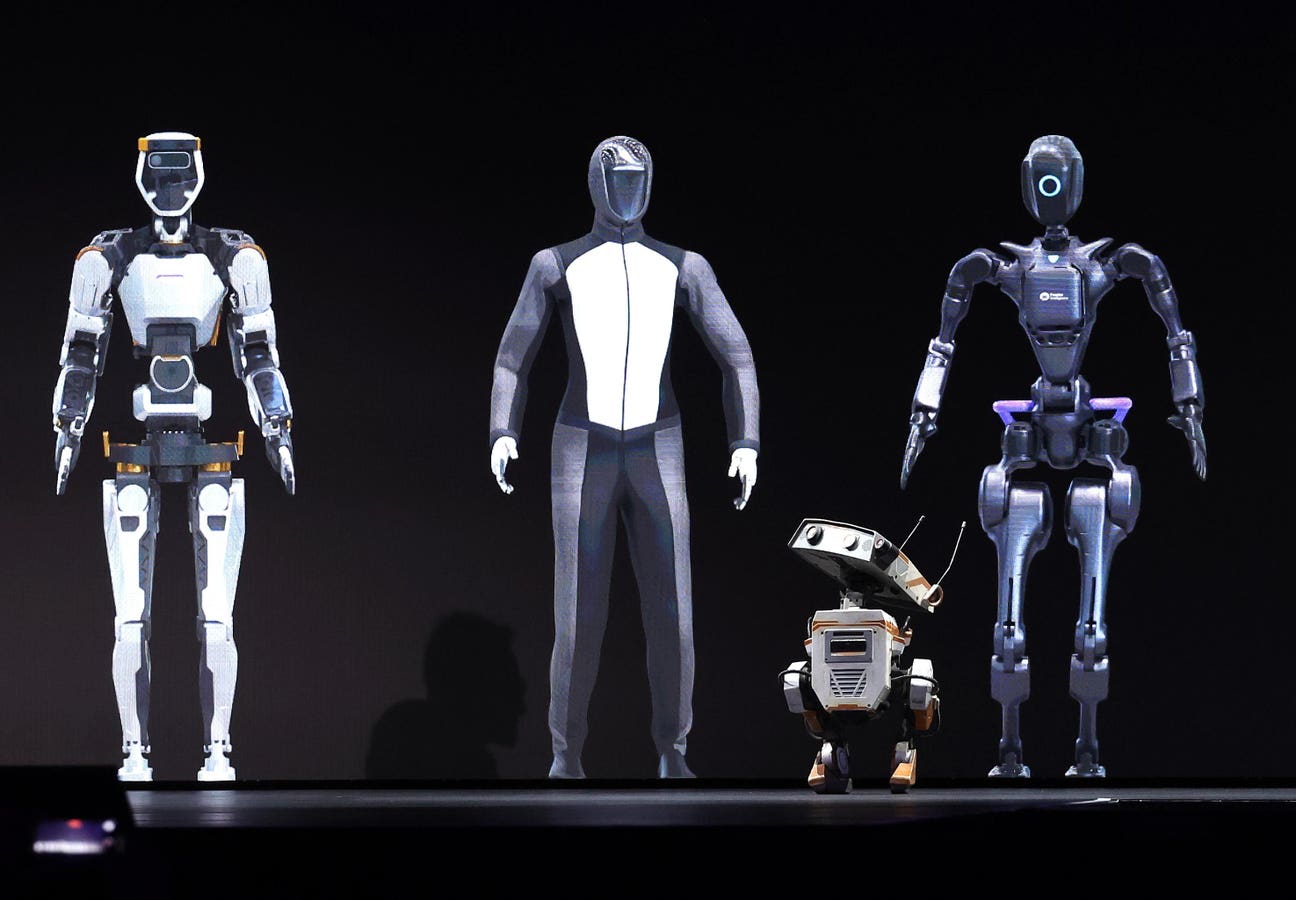

SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA – MARCH 18: A

In a world where AI agents are everywhere, how do we ensure that people still have agency?

One idea that’s surfacing, albeit in sort of a vague way, is similar to the concept of a service dog or emotional support animal: that a person would have a dedicated personal AI entity that works as their guardian angel in a world of peril.

Think about trying to navigate all of the AI stuff coming your way as a human: all of the scams, all of the drama of other people’s communications, not to mention government and business messaging churned out in automated ways.

“Consumers are out there trying to navigate a really complex marketplace, and as AI is injected into the marketplace by many companies, it’s probably going to become even harder for consumers to understand if they’re getting a good deal, to understand the different options out there when they’re making a purchase,” said Ginny Fahs of Consumer Reports in a recent panel aimed at an idea very much like this, the idea of personal defense AI. “And so an AI that is loyal to the consumer, loyal to us as individuals, first and foremost, is really going to be essential for building trust in these AI systems, and for … migrating to a more authentic economy.”

Fahs was among a set of expert panelists at Imagination in Action in April, and I found this to be one of the more compelling talks, not least because of past interviews I’ve seen in the last two years. Take data rights advocate Will.i.am, who famously coined the term “idatity” to talk about the intersection of personal data and technology. Anyway, my colleague Sandy Pentland moderated this group discussion, which covered a lot of thoughts on just how this kind of AI advocacy would work.

“There was a need to reform laws to keep up, to have electronic signatures, electronic contracts, automated transactions,” said panelist Dazza Greenwood of the Internet age, relating that to today’s efforts. “And I helped to write those laws as a young lawyer and technologist.”

Panelist Amir Sarhangi spoke about the value of trust and familiarity with a person’s AI advocate.

“Having that trust being established there, and having the ability to know who the agent is and who the enterprise is, becomes very important,” he said.

“Part of it is this general problem of, how do you make sure that agents don’t break laws, introduce unexpected liabilities, and (that they) represent the authentic interest of the consumer, and (that they can) actually be loyal, by design?” said panelist Tobin South, who got his PhD at MIT.

How It Might Work

Panelists also discussed some of the procedural elements of such technology.

“In collaboration with the Open ID Foundation, who kind of leads all the standards and protocols keeping our internet safe, we are pushing forward standards that can help make agents safe and reliable in this kind of new digital age,” South said.

Fahs talked about something her company developed called a “permission slip.”

“You could go to a company through the agent, and the agent would say to the company, ‘please delete this person’s data,’ or ‘please opt out of the sale of this person’s data,’” she said. “It was a version of an agentic interaction that was (prior to the explosion of AI), but where we really were getting an authorization from a user for a specific purpose to help them manage their data, and then going out to a company and managing that transaction, and then reporting back to the customer on how it went.”

On privacy, Greenwood discussed how systems would deal with laws like California’s CCPA, which he called a “mini-GDPR,” and encouraged people to use the term “fiduciary” to describe the agent’s responsibilities to the user.

Sarhangi talked about the history of building KYA.

“One of the things we started talking about is KYA which is, “know your agent,” and “know your agent” really is about understanding who’s behind the agent,” he said. “These agents will have wallets, basically on the internet, so you know what transactions are being conducted by the agent. And that’s really powerful, because when they do something that’s not good, then you have a good way of understanding what the history of that agent has been, and that will go as part of their … reputation.”

Crowdsourcing Consumer Information

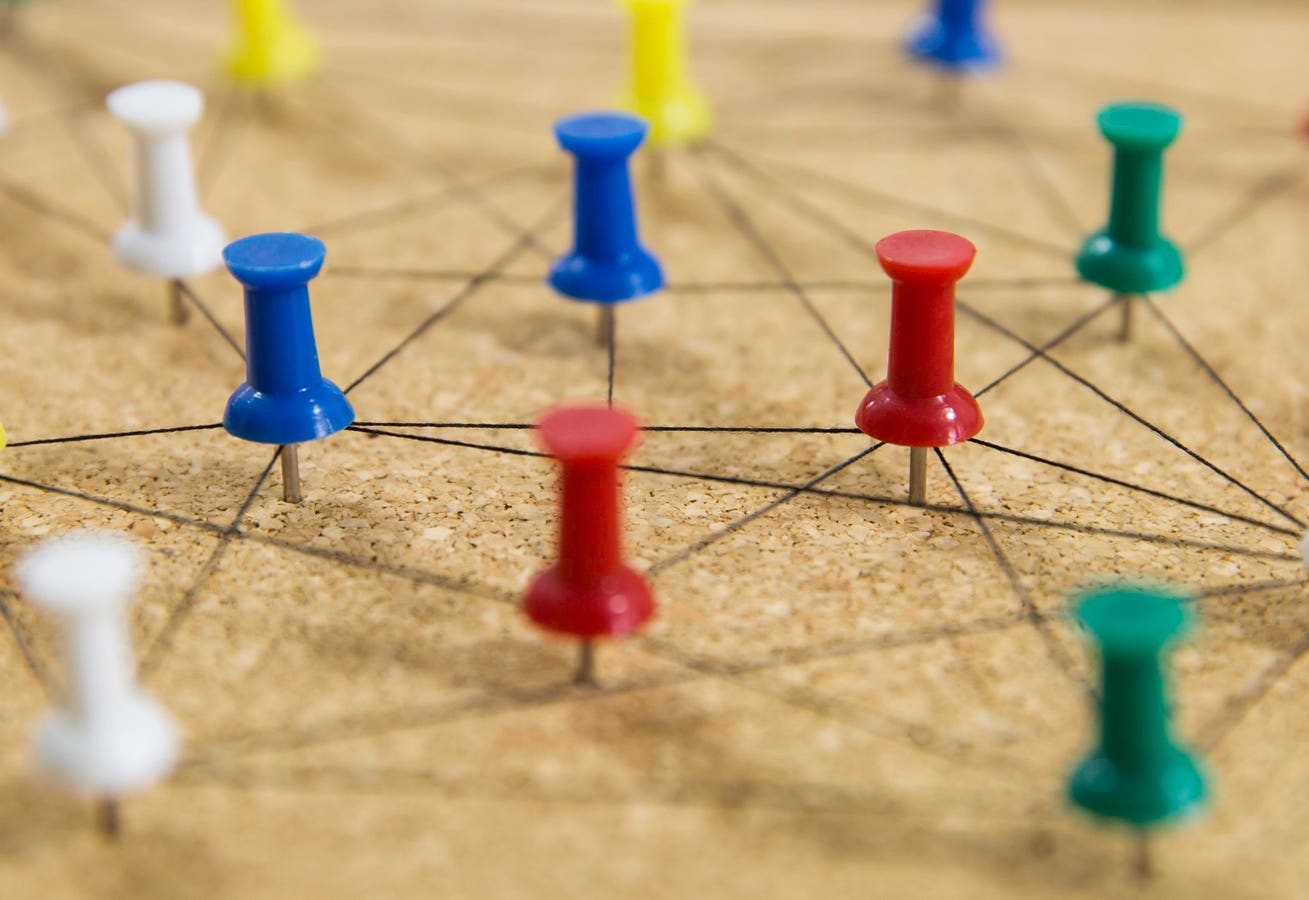

Another aspect of this that came up is the ability of the agents to put together their people’s experiences, and share them, to automate word of mouth.

“A really key type of a thing I’m excited about is what Consumer Reports does without thinking about it,” said Pentland, “which is compiling all the experiences of all your millions of members to know that ‘these blenders are good’ and ‘those blenders are bad,’ and ‘don’t buy that’ and ‘you don’t trust that dude over there.’ So once an agent is representing you, you can begin doing this automatically, where all the agents sort of talk about how these blenders are no good, right?”

Fahs agreed.

“I can so casually mention to my AI agent, ‘oh, this purchase, I don’t like that one feature’” she said. “And if that agent has a memory, and has the ability to coordinate and communicate with other agents, that becomes kind of known in the network, and it means that future consumers can purchase better, or future consumers have more awareness of that feature.”

South added some thoughts on data tools.

“There are many really cool cryptographic tools you can build to make the sharing of data really safe, right?” he said. “You don’t need to trust Google, to just own all your data, promise not to do anything wrong with it. There are real security tools you can build into this, and we’re seeing this explosion right now.”

South also mentioned NANDA, a protocol being developed by people like my colleague Ramesh Raskar at MIT. NANDA is a way to build a decentralized Internet with AI, and it seems likely to blossom into one of the supporting pillars of tomorrow’s global interface.

Agents and Agency

The panel also talked about some of the logistics, for instance: how will the agent really know what you want?

“You want the user to feel like they can provide very, very fine-grained permissions, but you also don’t want to be bugging them all the time saying, ‘Do I have permission for this? Do I have permission for that?’” Fahs said. “And so … what the interface is to articulate those preferences, and to, even, as the agent, have real awareness of the consumer’s intent, and where that can be extended, and where there really does need to be special additional permission granted, I think is, is a challenge that product managers and designers and many of us are going to be trying to thread the needle on.”

“One of the things that current LLMs don’t do very well is recognize what a specific person wants,” Pentland added. “In other words, values alignment for a specific person. It can do it for groups of people, sort of with big interviews, but an agent like this really wants to represent me, not necessarily you, or you. And I think one of the most interesting problems there is, how do we do that?”

“Finally, we have the tools that (resemble) something like fiduciary loyal agents,” Greenwood said.

“There’s an expression going around Stanford, which is: the limiting factor on AI is context: not the size of the window, but your ability to structure information, to feed it to the AI, both for understanding consumers, but to also do preference solicitation,” South said. “If you want the agent to act on your behalf, or an AI to do things you actually want, you need to extract that information somehow, and so both as individuals, making your data available to AI systems, but also as an organization, structuring information so that AIs can know how to work with your systems.”

The Race Toward Personal Advocacy

I think all of this is very necessary right now, in 2025, as we try to really integrate AI into our lives. This is happening, it seems, pretty much in real time, so this is the time to ask the questions, to find the answers, and to build the solutions.