Volvo’s FH Aero Electric promises up to 373 miles of 44-ton goods haulage.

The transition to electric cars is moving fast in the UK and Europe, but the same cannot be said of commercial vehicles – particularly trucks. While there is now a huge choice of EVs available for personal use, the development of electrified heavy haulage has been much slower. Tesla’s much-anticipated Semi has continually slipped with first customer deliveries now expected in March 2026. But one company leading the transition right now is Volvo Trucks. I talked to the Volvo Group Chief Technology Officer, Lars Stenqvist, about how his company is leading the decarbonization of road-based heavy goods delivery.

5,000 Electric Volvo Trucks On The Road

Despite the name, Volvo Group, which owns the Volvo Trucks brand, is a separate company to Volvo Cars, having been divided out in 1999. This means that while the passenger car division is now under the ownership of Chinese company Geely, the commercial vehicles are still Swedish, although Volvo Group has other collaborations. Flexis vans come from a collaboration with Renault Group and shipping company CMA CGM. Volvo Group also owns Renault Trucks.

Volvo Group’s electric commercial vehicle range is already extensive, and has delivered over 5,000 electric trucks worldwide since 2019, logging more than 100 million miles of haulage. This makes it the biggest seller of electric heavy goods vehicles globally. The company makes the FM, FMX, FL, and FH, with electric ranges from 300km (186 miles) to 450km (280 miles). Volvo Group also makes electric diggers and buses, with the latter having autonomous potential, which could be used for moving passengers around airports, for example.

Volvo Group also makes electric digging vehicles, as well as electric trucks.

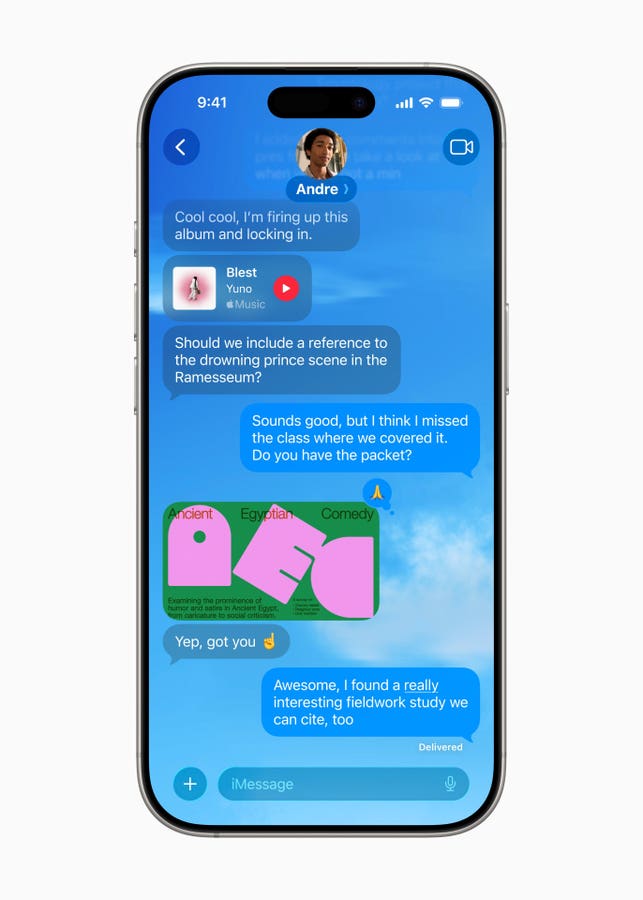

The Volvo FH Aero Electric is particularly important. Set to arrive later in 2025, this truck promises ranges up to 600km (373 miles), making long distance haulage possible. Having tested this vehicle myself on a private Volvo Group site, I found that, apart from the huge size of a 44-ton articulated truck, the FH Aero makes driving remarkably easy and not very noisy either. Sound and vibration contribute to driver fatigue, so the FH Aero can improve employee job satisfaction and safety.

“We are seen as pioneers, both in Europe and North America,” says Stenqvist. “We offer vehicles up to 44-ton tractor-trailer combinations suitable for up to regional haul right now. From next year, we will start to produce vehicles that are more optimized for long haul, with up to 780kWh electric energy on board. We are proof that you can electrify heavy haulage.”

Varying European Markets For Volvo Trucks

However, uptake of electric trucks varies greatly even in Europe, where personal EV sales are burgeoning. “It differs a lot between countries in Europe,” says Stenqvist. “If you take Europe overall, only 1.5% of heavy-duty trucks were registered as zero emission vehicles in the first quarter of 2025. That is almost zero, you could say, so that’s when you consider the glass to be half empty. If you consider the glass to be half full, then you must look at statistics from different countries. Then you have, for example, Switzerland, with around 11%; Norway, with around 9%; Sweden, north of 7%. When you come to a point around 10% then everyone sees that this is happening. This means that it will also be more interesting to invest in, for example, charging infrastructure, which is the true bottleneck to scale this to the levels where we need to be by 2030.”

Volvo Group is also helping with this lack of charging infrastructure. Although some countries including the UK have plenty of ultra-rapid DC chargers for passenger EVs, even 350kW is a bit puny if your truck has hundreds of kWh of batteries. At the EVS38 event in Gothenburg in June, Volvo Group was demonstrating its collaboration with Milence to deliver Megawatt charging. The demonstration only hit 684kW, averaging around 630kW, but Volvo Group claimed this was a limitation of the current truck generation, and future vehicles will charge faster. “That’s definitely the trend,” says Stenqvist. “If you have long-haul battery electric trucks with almost 800kWh on board, and you want to charge it during, let’s say, the lunch break of the driver, then you need to have power levels of 700-750 kilowatts, or up to 1MW.”

Megawatt charging will be essential for long-distance electric road haulage.

Strangely, despite the UK just posting June personal car sales figures where BEVs were a quarter of the market, it’s not one of the European countries leading with electric trucks yet. “UK is very low,” says Stenqvist. “Those countries where we see a clear uptake, around 10%, have good long-term incentive schemes in place. This makes it much easier for our customers to plan, because you must be long term when you’re investing in these vehicles. The best driver is when you have usage-based incentives. In Switzerland, they have zero road tax for zero emission vehicles. It’s very easy to remember: zero for zero. That means that they let the polluting technology pay for the transition. It’s a very smart move, and that would stimulate the uptake in other countries. There is no reason for any country in Europe not to achieve 10% right now, but to go above the 10%, you need to invest heavily in charging infrastructure.”

What About Hydrogen-Powered Volvo Trucks?

Not everyone is convinced that battery electrification is the way forward for heavy goods haulage. Although fleet solutions provider VEV disagrees, there are companies that believe hydrogen will be a better way forward, such as UK initiative HyHaul. Volvo Trucks has offerings both for hydrogen fuel cells and combustion, although these are not in full commercial production yet, unlike its BEVs.

“We are very committed to decarbonizing road transport infrastructure, and we are convinced that there will be more than one technology needed to deliver on that commitment,” says Stenqvist. “There are varying demands when it comes to different applications, but also different regions. There will be a lot of battery electric vehicles, but you will also see fuel cell electric vehicles operating on hydrogen. And we also believe that the combustion engine has a role to play in the long run in our industry. That’s why we are going broad.”

“You will see applications that are more suitable for different technologies, but you will see even more regions that have a sweet spot for the different technologies,” says Stenqvist. “One country where I’m very optimistic when it comes to hydrogen is India. India has a lot of potential for solar energy, and they can convert it to hydrogen at a very attractive price point. There are already today initiatives in India stimulating the uptake of hydrogen in the transport sector.”

Volvo is still pursuing other energy sources for its trucks including hydrogen.

The Middle East could also be a major player in a future hydrogen economy, as a replacement for its current oil business. “Since we will see a dramatic drop in the consumption of fossil-based fuels, they need something else,” says Stenqvist. “The Energy Minister of Saudi Arabia has a very clear focus on solar energy being converted to hydrogen and then exported either as liquid hydrogen or as ammonia. I’m convinced that you will see that being transported on ships. I even foresee that we will see pipeline distribution as well, carrying ammonia or hydrogen directly.”

Methanol has been gaining interest in China as a decarbonizing fuel for both passenger and long-haul heavy goods vehicles. Farizon’s Homtruck is a range-extending methanol vehicle, with 400km of pure electric range and another 1,000km with the methanol power. Around 5,000 trucks in China use Methanol M100, alongside 25-30,000 passenger vehicles. However, Stenqvist doesn’t see this fuel being significant outside China. “We have tested several different alternative renewable fuels,” he says. “We do not foresee that there will be huge volumes of methanol going forward. We are more optimistic when it comes to synthetic e-fuel diesels, but also very optimistic when it comes to different kinds of methane, such as biogas or liquefied biogas.”

Decarbonizing road haulage still faces many challenges, despite the success of Volvo Trucks so far. One of the main ones will be that the world’s largest economy, the USA, is backpedaling away from green technology towards climate change denial. “We are in rough waters right now,” says Stenqvist. “We see that the transformation is slowing down, but I’m convinced that so many people believe that this transformation is necessary. We have so much evidence when it comes to climate change, we know what we need to do. This will happen. The wheels are turning. I’m convinced the technology will continue to be developed to deliver electrified road haulage.”