Maria Montalvo speaks with emotion, her eyes shining as she recounts her reading experiences. She says she especially enjoys books by Isabel Allende, Octavia Butler, Toni Morrison, Erika L. Sánchez and John Grisham because, in her words, “reading makes you wiser and you learn how people live in other countries. It takes your mind to other places you can’t travel to.”

Montalvo isn’t an ordinary reader. During her incarceration at Edna Mahan Correctional Facility, a prison in New Jersey, she has participated in the activities of Freedom Reads, a nonprofit organization that has been promoting reading in U.S. prisons since 2020.

“Freedom Reads has brought books on different topics, and it’s very important to read because it makes you wiser,” Montalvo, 60, said in an interview with Noticias Telemundo. “Books change the prison climate; they change the way people think about themselves. This opens your mind and makes you want to change.”

Montalvo proudly recalled the arrival of the books at her prison in May.

“They brought two bookcases that are very symbolic and very important, because they relate to literature, justice and writers like Martin Luther King,” she said.

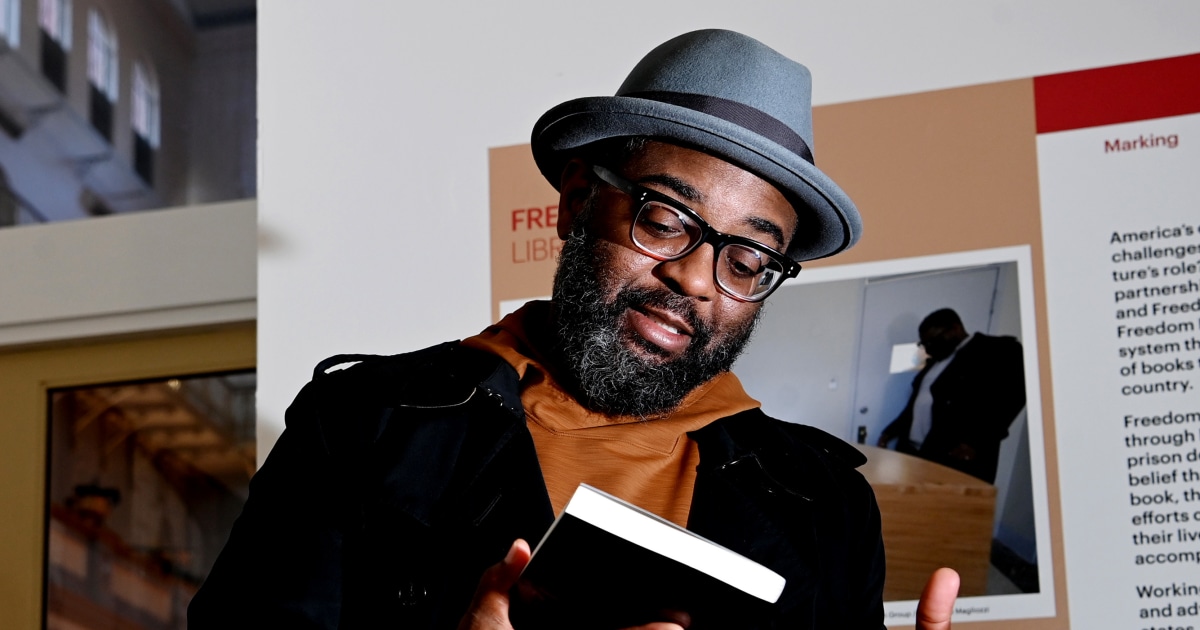

The origin of Freedom Reads is closely linked to the life of Reginald Dwayne Betts, who pleaded guilty to car theft at age 16 and was sentenced to nine years in the Virginia prison system.

“In prison, I discovered books. I became a poet and also a very good communicator. I was able to make friendships and connections that have lasted decades. Books gave me an understanding of the world,” Betts said in an interview with Noticias Telemundo.

Years later, Betts earned his law degree from Yale University, began publishing books of poetry and won prestigious Guggenheim and MacArthur fellowships, and in 2020, he was one of the founders of Freedom Reads, where he has worked to increase access to books for the U.S. prison population.

Finding reading material in prisons is difficult, Betts said. Most facilities have only one library, which is open a few hours a day and requires a permit to access it.

“I asked myself, ‘What would a library be?’ And I decided it would be a collection of 500 books, and I called it the Library of Freedom, because I believe in the idea that freedom begins with a book.”

Betts worked with architects at Mass Design, a nonprofit firm focused on architecture’s role in supporting communities and fostering societal healing, and they decided the bookcases’ structure should be curved. Many of them are built by former inmates, he said.

The libraries themselves are objects of design, each consisting of two to six freestanding bookshelves, handcrafted from maple, walnut or cherry wood. Betts has fitted the libraries into empty cells for easy access and designed each shelf to be 44 inches tall so as not to obstruct guards’ vision. The curves of each reading structure contrast with the harsh, angular architecture of the prison system.

“We want to show that it’s possible to be kind in places as violent and dangerous as some prisons, and we’re projecting our idea with libraries we make with our own hands,” he said.

Betts read several books in prison that changed his life. One was “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” by Gabriel García Márquez, which he said “taught [him] to understand Latin America and its people.”

According to figures from the Federal Bureau of Prisons, there are 46,334 Hispanic prisoners in the United States. Therefore, from the beginning of the project, bilingualism has been present, and Spanish-language titles are abundant.

“We have a list of more than 100 books in Spanish, and it continues to grow every year,” said David Pérez, Freedom Reads’ library coordinator.

According to the organization, Spanish-language books in the library’s permanent collection include “The House of Spirits,” by Isabel Allende; “I Am Not Your Perfect Mexican Daughter,” by Sánchez; “In the Time of the Butterflies,” by Julia Álvarez; and “The Shadow of the Wind,” by Carlos Ruiz Zafón, in addition to classics such as the novels of García Márquez and English-language works by Ernest Gaines, William Faulkner and George Orwell.

“I’m so pleased that my novel has reached so many unexpected places. I’m proud that incarcerated people find some relief in Julia’s story,” Sánchez said in an email about her book. “She’s a complicated protagonist who wants to escape her circumstances, like many women around the world.”

‘A lot of work ahead of us’

Maria Montalvo was convicted in 1996 of the deaths of her two children in a car fire, which she claimed at the trial was an accident; she’s serving a life sentence. During her trial, prosecutors acknowledged that she was “emotionally disturbed” during the incident, which contributed to her not being sentenced to death.

Years later, Montalvo says she has dedicated her time in prison to studying the problems of mass incarceration, reading literary works and engaging with other inmates in reading circles that discuss books in Spanish and English.

“There are many books in Spanish and English. So you can sit with many of the women who don’t speak English and read a book, but at the same time, another group is reading the same book in English, and you can have a conversation afterward,” she said.

Noticias Telemundo asked the Federal Bureau of Prisons for figures on its prisons’ literacy and reading initiatives, but it didn’t receive a response about the data. However, spokesperson Scott Taylor said in an email that the bureau closely monitors reading promotion programs like Freedom Reads, which “includes regular coordination meetings, staff training on safety expectations, and ongoing oversight to address any concerns.”

In addition, Taylor said, the bureau’s education branch has implemented a strategy focused on literacy and improving language skills for inmates who don’t speak English. “Bilingual instructions and materials are provided in Spanish and English, supported by digital tools that offer accessible resources for those learning English,” he wrote.

In 2023, research published by the Mackinac Public Policy Center, a nonprofit organization espousing free-market principles, found that prison-based reading, job training and education programs reduce the likelihood of recidivism by 14.8%. It also found a 6.9% increase in the likelihood of employment.

“I love having conversations with people inside prisons,” Pérez said. “They read a lot, and it moves you when you see them crying because they’ve read a poem or a novel — it’s unique.”

‘Having a voice’

Freedom Reads has installed 498 libraries in 50 adult and youth prisons across the United States. It has placed an estimated 280,000 books in the hands of inmates.

“Despite that success, we’ve probably reached less than 1%, maybe 0.5%, of the prisons in this country,” Betts said. “We’re not in any federal prisons yet. We’re only in 13 states, and we’re missing more than 30. So we have a lot of work ahead of us.”

Betts’ aim is to have libraries in 20,000 prisons.

Since 2023, Freedom Reads has administered the Inside Literary Prize, a literary award judged by incarcerated people. The inaugural award went to Imani Perry’s book “South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation,” selected by more than 200 judges from 12 prisons across six states.

By 2025, the competition had expanded to include more than 300 judges from 13 prisons in five states, and this year’s edition also included Puerto Rico. Montalvo was part of this year’s jury, and its decision will be announced Thursday.

“It’s a feeling of inclusion. It makes you realize that what we think about books and what we read matters,” Montalvo said excitedly. “It’s having a voice.”

An earlier version of this story was first published in Noticias Telemundo.