Private Equity’s Bid For Prime Energy Land

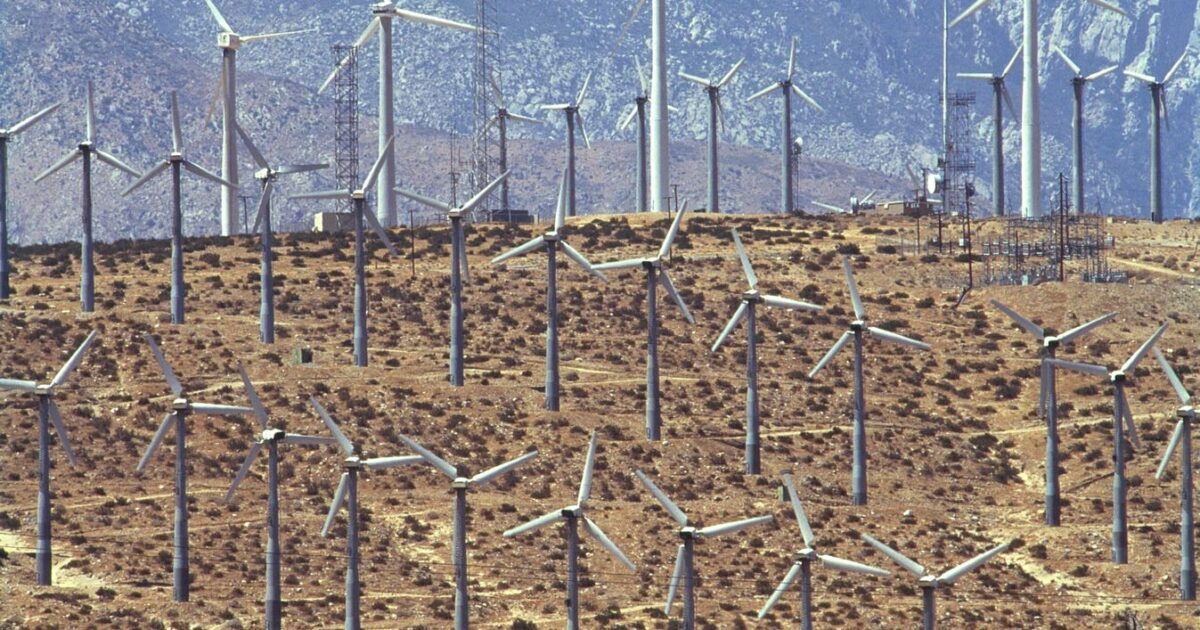

WHITEWATER, CALIFORNIA – DECEMBER 05 : Wind turbines produce energy at Whitewater Energy’s Wind … More

Private equity is quietly becoming one of the most potent forces in the future of clean energy—not just by financing solar panels and wind turbines but also by owning the land beneath them. These strategic moves could reshape how fast renewable power is deployed, who controls it, and whether communities benefit equitably.

TPG Global’s potential $2.34 billion acquisition of Altus Power marks just one of many high-profile deals this year. Stoa SA and EDF Brasil Holding are also vying for Geração Céu Azul SA, a Brazilian hydroelectric operator. Meanwhile, Brookfield Asset Management recently bought French renewables company Neoen for $7 billion, and Energy Capital Partners acquired Atlantica Sustainable Infrastructure for $2.6 billion. KKR has bid $3 billion for Germany’s Encavis.

“Wind and solar generation require at least 10 times as much land per unit of power produced than coal- or natural gas-fired power plants, including land disturbed to produce and transport the fossil fuels,” writes Samantha Gross, director of energy and climate for the Brookings Institution. “Additionally, wind and solar generation are located where the resource availability is best instead of where is most convenient for people and infrastructure, since their ‘fuel’ can’t be transported like fossil fuels.”

S&P Global said private equity and venture capital transactions in the global renewable energy sector hit nearly $15 billion in 2023, or 104 deals. Given the influx of artificial intelligence data centers, these ventures are critical as the global economy’s appetite for electricity will spike. Specifically, wind and solar are 17% of the U.S. energy mix and about 13% of the worldwide portfolio. China is the biggest user of renewable energy, accounting for 30% of its electricity pie.

As global electricity demand surges—driven by AI data centers, electric vehicles, and industrial electrification—private equity firms are racing to secure the most valuable real estate for renewables. They’re not just investing in clean power but also cornering the market on where it gets built. That raises red flags.

Consider that land with consistently strong winds, high solar insolation, and good grid access is hard to find. If private equity firms dominate these properties, it could drive up the prices of less desirable lands. That cost may ultimately fall on consumers through higher electricity prices or delayed clean energy rollouts. That’s an unhealthy development, particularly as nearly every nation races to decarbonize.

“Private equity is a growing force in renewable energy—specifically in wind and solar. It’s a natural fit for growth-oriented, long-term investors like private equity,” said the American Investment Council, which promotes private equity.

“In years past, many clean energy producers relied on government subsidies for capital,” it added. “With private equity sponsors, wind and solar companies get much more than that—a patient source of capital, knowledgeable sponsors who can help companies navigate regulatory hurdles, and growth-oriented investors who can push clean energy producers to new heights.”

Investors Pony Up

Dominion Energy’s first two turbines — part of a planned wind farm are about 30 miles off the … More

Over the last decade, the council has pegged domestic wind and solar investments at more than $130 billion. Since 2012, private equity sponsors have financed almost 3,000 energy enterprises across the spectrum, worth $617 billion. Private equity firms also back utility companies, including Puget Sound Energy, Hawaii Gas, El Paso Electric, AES Indiana, and People’s Gas, which serves Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Kentucky–states heavily involved in the old economy.

Don’t get me wrong: private equity is firstly interested in new tech–making better and cheaper stuff. But they’re also really into acquiring land now. The “losers” build projects far from transmission lines, which means expensive and time-consuming grid upgrades, especially in areas that don’t want them. That puts the private funds in an enviable position, leaving local communities and other energy producers disadvantaged.

“The electricity sector is transforming into a major growth area for both the U.S. and global economy, with forecasts projecting electricity demand will skyrocket” — to perhaps double over 15 years,” said Doug Kimmelman, founder of Energy Capital, in a statement. The 21st-century economy, with AI data centers and electric vehicles, drives the demand. The smart money thinks several steps ahead.

The influx of capital is a net positive, fueling innovation and scaling operations. Investors, though, bring more than money. They accelerate deployment. The International Renewable Energy Agency says the mission is to triple the use of renewables, adding at least 1 million megawatts of new capacity annually until 2030. We must reduce CO2 levels by 43% by 2030 and 60% by 2035.

There is a lurking concern: without careful oversight, it could also require a new kind of gatekeeping. Indeed, this ambitious expansion must be balanced with concerns about land acquisition. Policymakers can address both problems. Regulatory approaches can speak to fears over land concentration, while jurisdictions can prioritize community-owned projects through preferential permitting or financing.

No one wants to slow down the deployment of renewable energy. However, communities are increasingly wary of bearing environmental and social costs without proper safeguards, reminiscent of sentiments from coal-dependent regions. Given this history, it’s imperative to approach renewable energy development thoughtfully and inclusively.