How the deadly Texas floods unfolded, devastating Kerrville and Camp Mystic

Around 3:30 a.m., Guillén, the RV park owner, sees flashing rescue lights and a team trying to get a boat into the river. She joins her husband to check on their campsite. They find trailers tearing up from the ground and plunging into the river. It has been about 45 minutes since her last rounds, when the river seemed calm and the sheriff’s office had nothing to report. “It all changed that quickly,” she says. “It was horrifying.”

Guillén’s husband sees a father holding babies in the rushing water and tries to take them from him. But the current overpowers them, and they are gone.

Guillén goes door to door urging her guests to flee. Some run barefoot, barely clothed. In the dark she hears screams, cars honking, cabins crashing against trees.

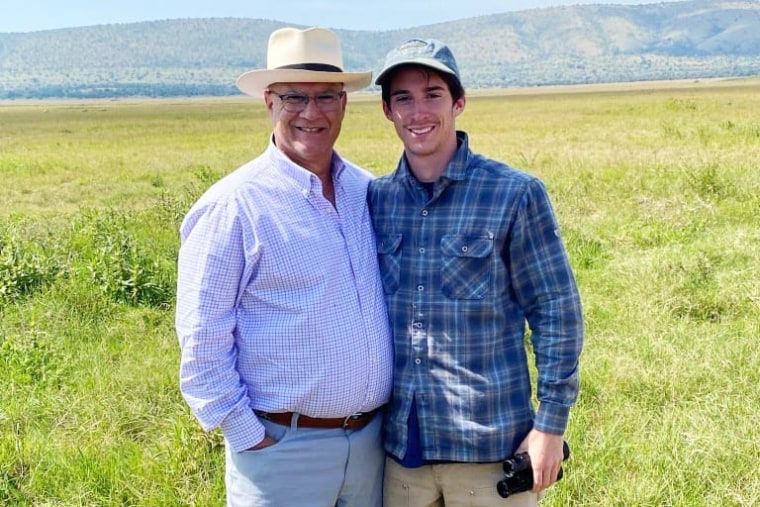

Around 4 a.m., Thad Heartfield is awakened at his south Texas home by a phone call from his 22-year-old son, Aidan, who is with his girlfriend and two others at their river cabin in Hunt. Aidan tells his dad that there’s 4 inches of water inside the cabin, but the water rises suddenly to about 4 feet. Heartfield urges his son to get out, to drive to the highway. But the water is rushing in so fast, their cars wash away.

Aidan tells his dad he has to help his girlfriend and hands his phone to one of the other girls, who within seconds tells Heartfield his son and the others are gone.

The phone goes dead.

A week later, Heartfield’s son is still missing; the friends’ bodies have been recovered.

The National Weather Service alerts escalate in urgency, but Kerr County hasn’t activated one of its emergency warning systems.

At 4:22 a.m., a volunteer firefighter in Ingram calls a Kerr County Sheriff’s Office dispatcher to say that he and his crew are having trouble getting anywhere because of the rising flood, according to audio obtained by NBC affiliate KXAN. He asks, “Is there any way we can send a CodeRed out to our Hunt residents asking them to find higher ground or stay home?” He is referring to a notification system that allows county authorities to send emergency alerts to people who have subscribed.

The dispatcher replies, “We have to get that approved with our supervisor. Just be advised we have the Texas water rescue en route.”

More than an hour passes before some residents receive a CodeRed alert; for others, no alert ever arrives.

Sometime after 4 a.m., Leitha, the Kerr County sheriff, is woken up and notified about the flooding. Officials won’t say whether the town’s emergency manager was awake, or what he and the other county officials were doing in the hours beforehand.

Around 4:45 a.m., Lucas and Irene Brake jump out of bed in their RV near the Guadalupe River and see the roiling water. Lucas calls his brother Robert in Fort Worth and asks him to call their parents, who are staying in a cabin nearby, and tell them to evacuate. Then Lucas opens the door to their RV “and we’re neck-deep in the flood. Our motor home is already floating away.” He gets his wife and their dogs into their Jeep and moves up to higher ground.

Robert calls their father, waking him, and asks him to help Lucas. Their father gets off the phone, saying: “I’m on my way.” But he’s in far more trouble.

Minutes after the call, Lucas runs toward his parents’ cabin to look for them. But when he gets there, it’s gone.

“It was chaos,” Irene says. “You see the people in their RVs floating past you but you can’t get to them because of how violently the river was flowing.”

“All you could hear is the people screaming for help,” she says. “You would hear trees snapping and the crush of the tiny cabins or the RVs just crashing into the RVs, just coming apart.”

A Kerrville Police Department patrol sergeant is making his way to work between 4 a.m. and 5 a.m. when he comes across the rising waters. From his patrol car, the sergeant sees dozens of people on rooftops. He gets on his PA system and tells them to hang on, be strong and that he will get help. According to a police spokesman, the sergeant drives to the nearby home of a detective and tells him, “It’s bad. I need you to get your gear on and come find me.”

Over the next hour, Kerrville police go door to door, waking people up, “convincing them that, yes, the floodwaters are coming and you need to leave now,” the spokesman, Jonathan Lamb, later says. During that time, more than 100 homes are evacuated and 200 people rescued, Lamb says.

Courtney Garrison, who lives above and manages The Hunt Store, a market near the banks of the Guadalupe, sees an officer warning people up and down the street at about 5:30 a.m.

Garrison, her daughter and their dog have been on their roof for an hour and she has called 911 four times, asking if someone can send a helicopter or a boat.

“I see you guys,” the officer yells out on his bullhorn, but he tells Garrison he is unable to help.

At 4:40 a.m., RickyRay Robertson, a pastor who lives in a cabin on the Guadalupe in Kerrville, is jolted awake by police sirens. Grabbing his gun and his cat Astros, Robertson notices that the river has breached a dam and is cresting a hill behind his cabin. He hurries to his brother’s house next door, kicks in the door, wakes him up, helps him into the driveway and heads across the street for his truck. Before he makes it, his brother, who does not walk well, yells for help and Robertson turns around to see the water rising around him.

Robertson dashes back and manages to pull his brother with him to the truck, and they drive off through a neighbor’s yard. Not long after, the river washes away Robertson’s cabin. He is grateful for the police sirens. “They saved our lives by just waking us up,” he says.

The county’s first alert finally goes out on social media at about 5:30 a.m.

Around the same time, Kerrville Mayor Joe Herring is awakened by the city manager. “We did not know, we did not know,” he says of the flooding. “I wasn’t alerted. I had received zero alerts beforehand. They did not come.”

Nine-year-old Birdie Miller spends four hours in the pouring rain in her pajamas with her bunkmates on the hillside at Camp Mystic. After dawn, the waters recede enough to walk to the recreation center, where she’s reunited with her big sister Genevieve.

The alerts keep coming as the danger shifts downstream.

Counselors start to move the girls from the rec center to a newer part of the camp: Camp Mystic Cypress Lake. It is dry and warm, and there is food and water. The campers and counselors wait for helicopters to arrive. As she flies off with 14 others, Lucy Kennedy looks at the river and the camp she loves. It is ruined.

They land at a nearby high school’s football field, where Lucy is carried barefoot because she has given her Crocs to another girl. She is safe, but she knows that many are not. During the nighttime evacuation, she watched a friend get pulled away by the current.

Birdie is the first of the Miller girls to be airlifted out. Her sisters soon follow to safety.

Schoepf waits as the sun rises to see the damage around the home she is sheltering in with her boyfriend. They decide it’s safe to head back to the River Inn, passing demolished homes along the way.