But a joint investigation by KFF Health News and NBC News found that Sono Bello and other cosmetic surgery chains have been the target of scores of medical malpractice and negligence lawsuits alleging disfiguring injuries — including 12 wrongful death cases filed over the past seven years.Injured patients have accused the chains of hiring doctors with minimal cosmetic surgery training, of failing to recognize and treat life-threatening infections and other dangerous surgical complications, and of high-pressure sales tactics that minimized safety risks, court records show. Sono Bello and the other companies have denied the allegations in court.

“These people promise to turn you into the fairest person in the land, and the risks aren’t often worth the reality,” said Sean Domnick, a Florida attorney who heads the American Association for Justice, a trial lawyers group.

Sono Bello’s Centeno disagrees. He said the company’s mission is to “help each and every one of our patients live their best lives now.” Sono Bello offers “life-changing transformations” that enhance a person’s “appearance as well as their quality of life,” said Centeno, a surgeon himself at the company’s Troy, Michigan, office.

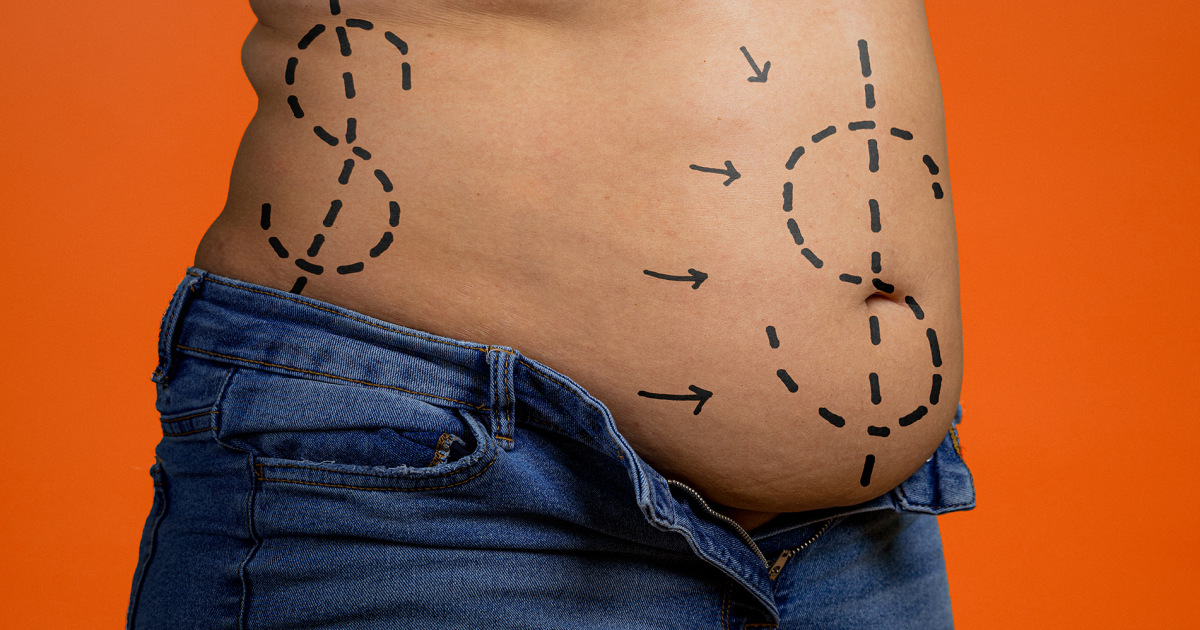

The doctors who perform such surgeries, court records show, are sometimes paid more for taking on patients with a high body mass, as obesity raises the risk of devastating complications.

And as the chains grow, there’s little regulatory oversight. While the Food and Drug Administration maintains a database of complaints about drugs or medical devices, there’s nothing similar for cosmetic surgeries.

Schaeffer had liposuction at Sono Bello in January 2024 and was satisfied with the results. On the morning of March 29, 2024, she went in for more liposuction and a mini-tummy tuck that Sono Bello calls AbEX. The medical staff gave her Xanax and the painkiller oxycodone in pill form, according to medical records Sono Bello turned over to Schaeffer’s attorney. During the procedure, she received an infusion of lidocaine to numb the area but remained awake. Sono Bello says the local anesthesia is safer and promotes faster healing with “minimal discomfort,” so patients may return to work or other normal activities within a week.

That didn’t happen for Schaeffer, who said she felt so much pain during the operation that she began to cry and “begged” the doctor to stop near the end.

“I said, ‘I don’t care what I look like,’” she said in an interview. “‘I can’t handle the pain.’”

Two days later she spiked a fever, and a day after that her pubic area swelled up “severely,” she said. Sono Bello medical staff told her that was normal and that she was fine, she said. Two days later, however, blood and fluid spilled out of her stomach when she got up, she said.

On one visit to the office, Herrera told her she required surgery at a hospital to treat her wounds. But, she recounted, Herrera said he couldn’t arrange that because he was an obstetrician, not a plastic surgeon, and didn’t have hospital privileges locally. Herrera has hospital privileges in the Orlando area, about 140 miles southwest of Jacksonville.

“I was just in utter shock,” Schaeffer said.

Sono Bello spokesperson Mark Firmani said the company does not require its doctors to have local hospital privileges, though many do have them.

Centeno said Schaeffer’s painful experience is not common.

“The reality is that over 90% of our patients who have our procedures completed are extremely comfortable during the procedure and they do quite well,” he said. Patients of Sono Bello and some other clinics also have complained to the Better Business Bureau of unexpectedly painful procedures.

Centeno said that Herrera still works for the company, but the doctor’s name does not appear on the company’s Jacksonville website. Herrera runs an OB-GYN and aesthetics practice, which includes skin care treatments, in Winter Garden, Florida, near Orlando, and is board-certified by the American Board of Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Sono Bello has considered him a rising star; Herrera’s work in 2023 won Sono Bello’s annual “New Talent Award,” given to a company doctor who exhibits “exceptional technical skills, productivity, and off-the-charts brand loyalty.”

Herrera completed a Sono Bello fellowship program that teaches a “suite of aesthetic procedures” in a six- to eight-week course under the direction of a company surgeon. The company says the fellowship offers “patient-focused training in awake total body contouring and skin excision procedures.” Sono Bello allows physicians who have completed formal residencies in more than half a dozen types of surgery to apply for its fellowship.

In a post on a Sono Bello website, Herrera said that before taking the fellowship course, he “had been a skilled surgeon for over 13 years with extensive experience in other areas but limited knowledge on body sculpting.” Herrera did not respond to calls and emails requesting comment and directed Sono Bello to respond on his behalf. Company spokesperson Firmani said Herrera is still a member of the Sono Bello team.

Many established plastic surgeons who spoke with KFF Health News and NBC News worry that chain surgery groups may be inclined to spend more effort on marketing and sales than on making sure their doctors are properly credentialed and capable of handling any complications that arise.

Medical practices owned by private equity or investment firms have more money to spend drawing in patients, and “the ability to operate and provide quality patient care is now less important,” said Mark Domanski, a plastic surgeon in northern Virginia.

Doctor entrepreneurs

Formed in 2008 by entrepreneurial physician Tom Garrison, Sono Bello now runs more than 100 centers nationwide. Private equity investors have pumped $816 million into the company, most of it since 2023, according to PitchBook, which tracks the industry. Sono Bello advertises widely on television and online, aimed at what one major investor termed the “everyday woman and man.” It has advertised having “150+ board-certified surgeons who have performed over 300,000 laser lipo & body contouring procedures.”

Sono Bello limits its offerings to services such as liposuction and its version of tummy tucks, which it believes its surgeons have mastered. It does not perform Brazilian butt lifts, or fat transfers, though many other cosmetic surgery chains do.

While Sono Bello boasts that the vast majority of its patients are satisfied, court records show that allegations of substandard medical care have trailed its rapid growth.

Sono Bello and its corporate affiliates and surgeons have defended more than 60 medical malpractice cases, including four suits involving patient deaths, since April 2013, court records show. Sono Bello has settled three of four wrongful death cases filed since May 2018, while one is pending, court records show.

Schaeffer’s suit in Jacksonville is among at least 19 filed since the start of March 2023. Many are pending in the courts, and the company has denied the allegations.

Other physicians who have extended their brands to multiple cities and relied heavily on social media and splashy websites to bring in patients have also faced lawsuits.

Mia Aesthetics, formed in 2017 by Texas surgeon Sergio Alvarez, runs a dozen cosmetic surgery clinics from Miami to Las Vegas. Mia Aesthetics provides “the highest quality plastic surgery at affordable prices proving that being beautiful and saving money are two realities that can exist simultaneously,” its website says. Alvarez is a board-certified plastic surgeon.

Patients filed at least 30 medical negligence cases against Mia Aesthetics and its affiliates from November 2020 through March of this year, court records show. A dozen suits target its Miami surgery center. The company has sought, and often won, dismissal of malpractice suits because patients signed contracts agreeing to arbitration of any disputes, court dockets show. Alvarez did not respond to requests for comment.

Owned by New York physician Sergey Voskin since 2016, Goals Aesthetics and Plastic Surgery has branched out from a small cosmetic surgery office in the Brooklyn borough of New York City to a network of a dozen surgery centers it manages in eight states.

Goals clinics and affiliated surgeons have been named as defendants in at least 40 malpractice suits filed from October 2018 through March, court records show. The Atlanta branch accounted for more than 20 such cases in Georgia courts from September 2022 through June 2024. Most are pending. Goals defended two lawsuits brought by the families of New York patients who died shortly after having liposuction procedures, court records show. Goals denied the allegations and won dismissal of some cases by invoking arbitration agreements, according to court dockets. The company says these agreements are commonly used throughout the medical industry.

Voskin declined to be interviewed. In a statement, Goals lawyer Joshua Lurie said the medical offices it manages have performed more than 10,000 procedures and have “one of, if not the highest track records of safety among similar types of medical practices.”

Lurie said the “vast majority” of malpractice claims are “meritless.” These “bad faith filings create an implication of risk when none exist and when, again, there is a very negligible negative outcome from surgery compared to the total procedures performed,” he wrote.

No Guarantees

Malpractice suits by themselves are not proof of wrongdoing. Nobody tracks the outcome of these lawsuits, which often are settled under confidential terms that keep key details out of public view and prohibit patients from discussing their experiences. Surgeons often argue that complications are a risk of surgery and that a poor outcome doesn’t mean the doctor was negligent. To prove negligence, injured patients generally must show their care fell below what a reasonably prudent doctor with similar training would have done.

That can be a challenge. Typically, the surgery chains fight back by arguing that complications are a risk of any surgical procedure and that they never guarantee results.

Before their procedures, patients must sign consent forms acknowledging their expectations must be “realistic” and that complications or dissatisfaction with the result does not necessarily mean the surgeon botched the job. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons investigates ethics complaints against its members, but not allegations of incompetence or malpractice.

Some presurgery contracts allow for low-cost “revisions” for disgruntled patients. Sono Bello has offered a “satisfaction commitment,” which states: “If your surgeon’s evaluation determines your results to be deficient, we will touch up the area at no cost to you.”

Other contracts contain disclaimers, such as reminding patients that dramatic “before and after” photos widely shown in online advertisements and other solicitations may not reflect typical results.

Demonstrating the influence of social media in driving sales, Goals once required patients to sign a nondisparagement clause. The contract stated that patients who bad-mouth the company on social media without first giving the company “an opportunity to remedy any alleged issues” agree to pay damages of $10,000 for each violation.

In a civil investigation of Goals’ marketing tactics, Georgia Attorney General Chris Carr alleged that policy and others violated state consumer protection laws. In September 2022, Goals agreed to stop using the nondisparagement clause and to pay the state $119,480 to settle the matter, without admitting any wrongdoing.

Both Goals and Mia Aesthetics have clauses in their service contracts that require arbitration of any disputes in lieu of court action, a process many consumer advocates believe favors the industry. These agreements are becoming more common among plastic surgeons. The arbitration clauses have prevented some aggrieved patients from getting their day in court.

That happened in a wrongful death case filed by the family of Angela Mendez, 57, who was found dead in her apartment a day after liposuction at a Goals office in New York City in March 2021. She died from a pulmonary thromboembolism, a blood clot in her lung, as a complication of cosmetic surgery, according to an autopsy report.

Her family sued the company alleging negligence. But in June 2024 a judge ruled that Mendez had signed a form requiring that the case be heard in arbitration and dismissed the lawsuit.

Attorney Gary Zucker, who represents the family, is appealing. “It’s been a one-two punch for the family,” Zucker said.

Goals attorney Lurie called arbitration “a common practice throughout the industry and many industries” that is “intended to speed the process to come to resolutions in a more expedited fashion.” In a 2023 deposition, Lurie said patients can opt out of the arbitration agreement, which “has happened multiple times.”

‘A Hard Sell’

When Erin Schaeffer first visited Sono Bello, a sales agent told her she was a “perfect candidate” for a tummy tuck procedure, she said in an interview with KFF Health News and NBC News.

Though she wanted to think about it and talk it over with her family, she says the salesperson persuaded her to go ahead. Because cosmetic surgery is elective, insurance doesn’t cover it. Schaeffer made a down payment and signed up for a credit plan through outside companies to repay most of the $19,838 bill over a five-year period, according to her medical records. She said she’s now paying $420 a month.

“I definitely felt like it was a hard sell,” Schaeffer said. “She didn’t want me to leave out of there without putting money down on it.”

Schaeffer said she didn’t meet the doctor until about a week before the procedure, and only briefly. Some patients suing other companies have argued in court filings that they didn’t meet the surgeon until the day of their operations, a practice that draws sharp criticism from more traditional surgeons.

Scott Hollenbeck, president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, said patients need time with their doctor to fully understand the pros and cons of surgery and shouldn’t be pressured into quick decisions.

“It is not possible to do that when you see the doctor an hour before surgery for the first time,” he said. “You should have time to process what they told you, think about it, and make a decision.”

“That is best done with a surgeon, not a marketer,” Hollenbeck said.

Good Candidates

Many plastic surgeons discourage obese people from undergoing liposuction and other cosmetic procedures because of an elevated risk of infections and other serious medical complications. Candidates are considered obese at a body mass index of 30 or above. Sono Bello patients have an average BMI of 31, according to Centeno. At the time of her surgery, Schaeffer had a BMI of 36.

But there’s no consensus on who should be turned away because of their size — and policies vary.

Sono Bello says its AbEX tummy tuck can be done safely with a body mass index as high as 42, well beyond the body mass limits for a traditional abdominoplasty done using general anesthesia. The AbEX removes loose and sagging skin around the stomach “to achieve a more toned and sculpted look,” according to the company.

Centeno said that high BMI “does confer additional risk, which can be managed.” But he said it would be “discriminatory, unethical and inappropriate for Sono Bello or any other medical practice to deny care to a patient based solely on their BMI.”

Yet high-BMI patients have alleged they suffered devastating complications, according to KFF Health News’ review of court cases filed against Sono Bello and other companies.

One patient is Marissa Edwards, then 45, a California medical receptionist with three children. At 5 feet, 3 inches tall, she weighed 237 pounds, with a body mass index of 41.

She had AbEX and liposuction at a Sono Bello clinic in San Diego on Oct. 11, 2022, according to court filings. During an office visit eight days later, she complained of swelling and pain in her abdomen, but a nurse “dismissed her complaints,” according to the suit. On Nov. 4, Edwards noticed the incision was opening, while a rash formed around her belly button. In a text to Sono Bello, she attached a photo of her wound, which, the suit alleges, should have alerted the staff that it needed “immediate evaluation by a qualified medical professional.”

On Nov. 5, she woke up “feeling extremely hot” and “nearly fainted,” according to her complaint. Her husband drove her to an urgent care center, which diagnosed her with sepsis and rushed her to a hospital by ambulance.

When she awoke the next morning, her bedsheets were soaked with body fluid. As she stood up, “fluid began to pour out of her stomach and hit the floor,” according to the complaint. She spent six days in the hospital.

Edwards alleges in her lawsuit that Sono Bello’s medical staff failed to recognize and respond to early signs of trouble.

“I have sepsis and could have died,” she texted to Sono Bello’s office line, according to court documents. “I am very upset.”

In one text that was included in her lawsuit, she wrote: “So I would appreciate some type of empathy from you!! If you only knew what I have been through and you went through this I’m sure you wouldn’t be giving me this snotty attitude.”

Sono Bello denies any negligence. In a court filing, the company noted that infections are a risk of surgery, and that Edwards had signed a consent form that stated in part: “The practice of medicine and surgery is not an exact science and results are not guaranteed.” Sono Bello filed a motion for summary judgment that argued her care was not negligent and “not a substantial factor” in causing her alleged injuries. The case was settled earlier this month under confidential terms.

Value Units

While patients with high BMI are riskier, they also are more lucrative for Sono Bello surgeons, court records show.

The company pays its surgeons for procedures based in part on the patient’s BMI, using a formula it calls a “surgical value unit.”

The compensation plan surfaced in a lawsuit filed in December 2023 by Shirley Webb, then a 79-year-old Nevada woman. Hoping to slim down for a dream cruise, she paid $14,703 for an AbEX tummy tuck and liposuction of her stomach at the Sono Bello branch in Las Vegas.

Eighteen days after her operation, she was “oozing and bleeding” from her surgical wounds and her son rushed her to a hospital, where doctors diagnosed “severe sepsis with shock,” according to the complaint. She spent several months in hospitals and rehabilitation care, running up medical bills of more than $2.6 million, her lawyer stated during a deposition.

Lloyd Krieger, a California plastic surgeon who served as a medical expert for Webb’s legal team, said the operations never should have happened because she was at “very high risk for multiple procedures given her advanced age and high BMI,” according to the suit.

In a court deposition, Sono Bello surgeon Charles Kim testified that operating on Webb earned him “surgical value units” that boosted his pay to about $2,000 for the procedure.

Sono Bello and Kim denied Webb’s negligence claims and the parties settled the case in early 2025 under confidential terms, court records show.

Centeno said Sono Bello surgeons are paid more for higher-BMI patients because they “require additional work and additional complexity in terms of decision-making.” He added that “our high-BMI patients routinely undergo our procedures safely with an extremely high patient satisfaction rate.”

Schaeffer said people hoping to reshape their bodies need to do a lot of research before plunging ahead with plastic surgery. She said she was hoping to get rid of excess skin and fat after dropping 100 pounds.

Instead, she missed seven weeks of work recovering from her tummy tuck in Jacksonville. “I went into this procedure to try to make myself feel better after losing the weight, and I came out with something even worse,” she said.

“I trusted. I believed in what they told me, which I think most people do,” Schaeffer said.

“Not anymore.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.