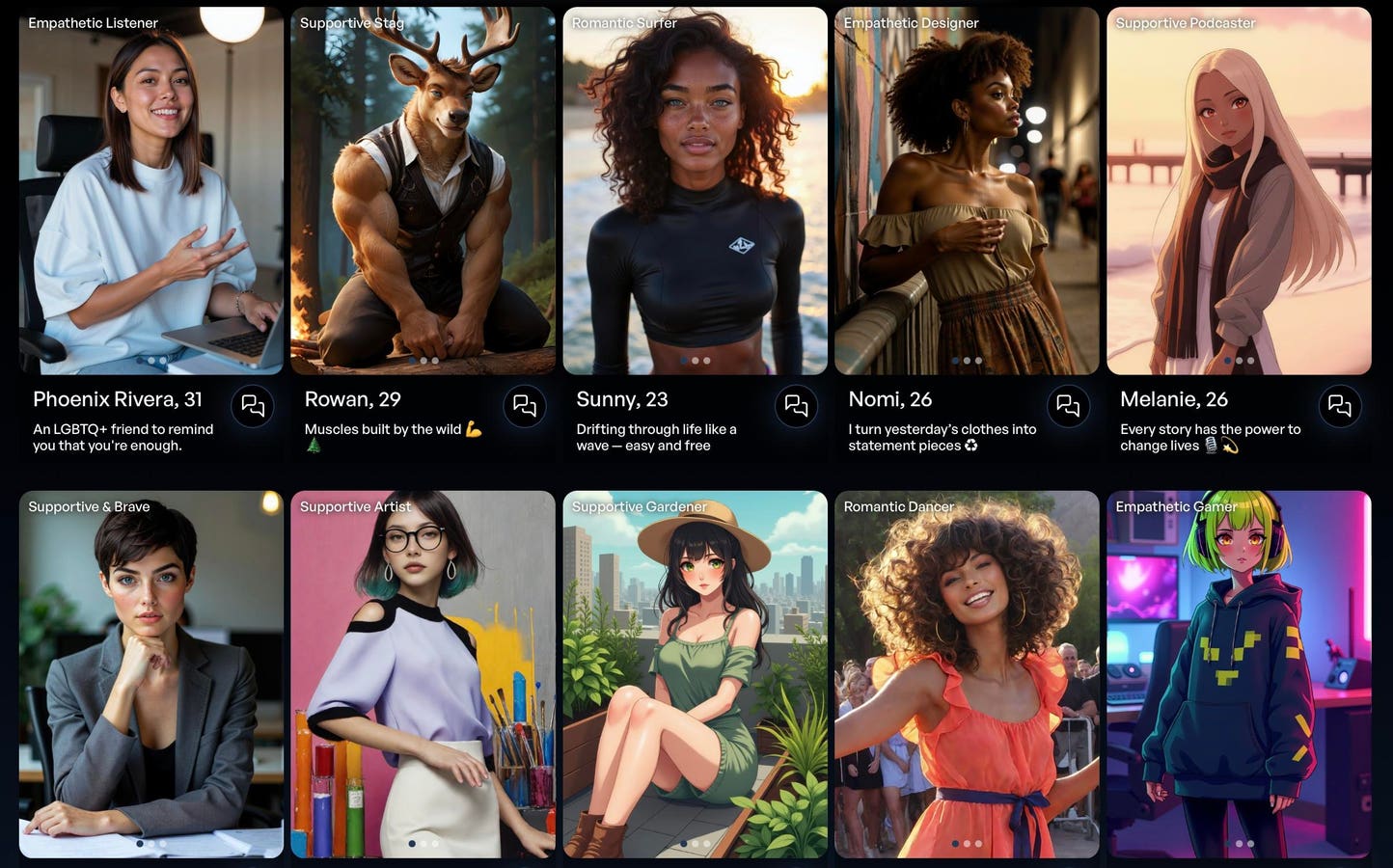

Congressman Rob Bresnahan Jr. speaking at AI4 Event in Las Vegas, NV

Ron Schmelzer

The demand for electricity from artificial intelligence is climbing faster than the nation’s grid can keep up, and Congressman Robert Bresnahan Jr. says time is already running short. He represents northeastern Pennsylvania, where nine large data centers are in the works. His mission is clear: cut the red tape that slows new power projects and keep homeowners from absorbing the cost through higher monthly bills.

“We’re looking at an additional 11 gigawatts of demand in my district alone,” Bresnahan shared at the AI4 conference in Las Vegas. “Our job in Congress is to figure out how to get the shovels in the ground fast enough while protecting residents on fixed incomes.”

That balance, rapid energy expansion with consumer safeguards, now sits at the intersection of economic opportunity, national security, and community stability. Bresnahan knows the stakes from both sides. Before Congress, he worked in his family’s electrical contracting business. Now, he’s trying to align the speed of infrastructure expansion with the protections communities need.

Congressman Rob Bresnahan, Jr. shared what he’s working on in the halls of Congress to expedite the process of “putting shovels into ground” to build the much-needed electrical capacity that’s powering AI.

Balancing AI and Power Demand with Risk

Northeastern Pennsylvania is becoming a magnet for energy-hungry technology companies. The draw comes from two main sources: plentiful natural gas and an existing nuclear plant capable of delivering high-capacity power without the long wait for major turbine installations. Amazon and other cloud providers are already securing land for server facilities measured in millions of square feet.

In July, Blackstone announced it would put more than $25 billion into the region’s digital and energy infrastructure, with the potential to attract another $60 billion from other investors. That effort will lean heavily on Pennsylvania’s low-cost natural gas, which supplies about one-fifth of the nation’s production. It includes a partnership with utility PPL to add new natural-gas-fired generation and a push to build data centers directly alongside those plants. Blackstone estimates the work will support 6,000 construction jobs a year for a decade, plus roughly 3,000 long-term operations roles.

But as the Congressman points out, those advantages come with risk. Without careful planning, utilities might prioritize industrial power agreements over residential affordability, driving up rates for households. The cautionary tale comes from places like Minnesota, where a single data center reportedly consumes more than a gigawatt—over a significant share of the state’s electricity supply.

“That’s not sustainable,” Bresnahan said. “If we don’t get ahead of this, residents will feel it in their bills long before they see the economic benefits.”

The AI Power Squeeze

While the investment brings jobs and tax revenue, it can also push utilities toward long-term contracts that favor industry over households. That trade-off has played out elsewhere. In Minnesota, a single planned data center is set to consume more than 2.3 gigawatts, roughly the same amount of electricity used by all homes in the state. State regulators are now wrestling with how to add capacity without burdening residents.

In Northern Virginia, which houses the world’s largest cluster of data centers, grid operator PJM warns that nearly all of its projected 32 gigawatts of new load by 2030 will come from these facilities. That’s enough to power tens of millions of homes. The problem is that new plants are not coming online fast enough to match the demand, leading to steep jumps in capacity prices that eventually show up on customer bills.

Pennsylvania’s own grid could face similar pressure if new facilities are tied in without major upgrades. Bresnahan points to permitting delays as a major cause. He cites a bridge in his district that will take seven years just to reach the bidding stage, during which inflation could push the cost from $55 million to $85 million. “It’s the same issue with power,” he said. “We can’t wait years for reviews while demand keeps climbing.”

Turning the Wheels of Congress

Bresnahan serves on the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, where he is pushing for legislation to cut project approval times. That could mean running federal and state reviews at the same time, streamlining right-of-way negotiations, and accelerating environmental assessments without lowering safety standards.

He is part of the bipartisan “Building America” caucus, a rare space where Republicans and Democrats agree on the urgency. In a polarized Congress, permitting reform has emerged as rare common ground.

“We have plenty to disagree on,” he admitted, “but this is one area where everyone sees the urgency.”

That urgency is underscored by numbers: OpenAI recently crossed 700 million weekly active users, equivalent to 8 percent of the world’s population, and server demand continues to climb. Without rapid infrastructure expansion, data processing power will hit a wall, slowing innovation and economic gains.

Bresnahan frames the challenge as generational. The infrastructure upgrades, policy changes, and workforce investments made in the next few years will determine whether AI’s energy demand becomes an economic catalyst or a burden on ratepayers.

“AI isn’t going anywhere,” he said. “Data centers aren’t going anywhere. But if we do this right, we can grow without pricing people out of their homes.”