History is not just a record of what happened, it is a well of wisdom we can draw from to guide our actions today and in the future. Some dates are burned into our collective memory, such as Aug. 6 and 9, 1945, when nuclear weapons were used in war for the first and only time. Others are nearly forgotten.

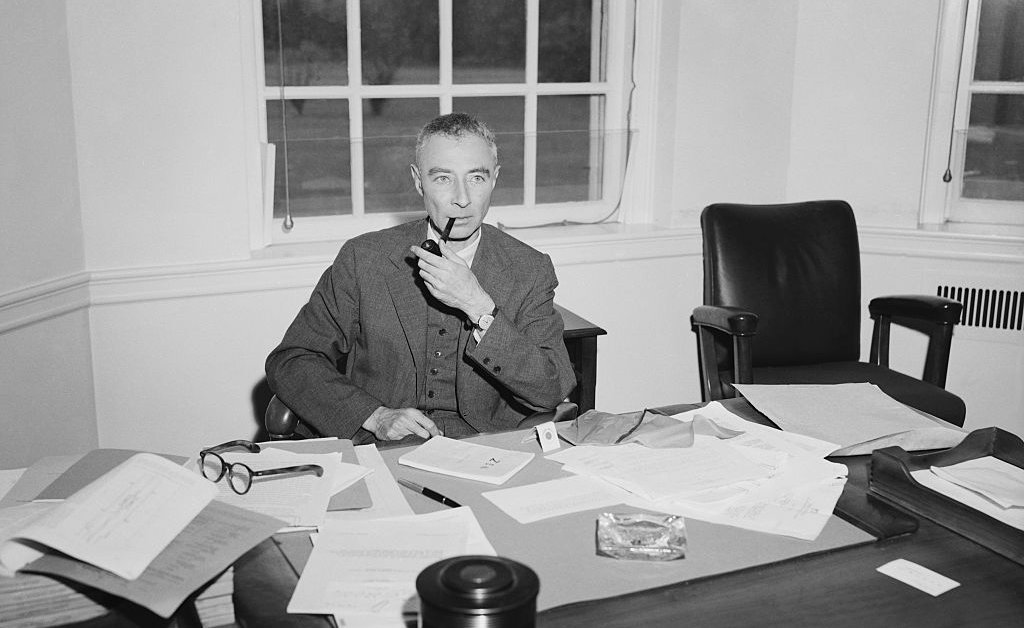

One of those forgotten days is Aug. 17, 1945. Acting on behalf of the Scientific Panel of the Interim Committee, my grandfather, J. Robert Oppenheimer wrote advice from the top scientists on the Manhattan Project in a letter to Secretary of War Henry Stimson. Just a week after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the letter offered advice so rooted in first principles that all of it remains true 80 years later: no nation can achieve absolute security through nuclear dominance. Considering this reality, global leaders must collaborate to resolve the underlying tensions between their nations to achieve no less than making future wars impossible.

“We are not only unable to outline a program that would assure to this nation for the next decades hegemony in the field of atomic weapons; we are equally unable to ensure that such hegemony, if achieved, could protect us from the most terrible destruction,” he wrote 80 years ago.

During the war, scientists like Niels Bohr and my grandfather hoped the atomic bomb’s terrible power might end all wars between great powers. They believed that once total war was recognized as unwinnable, nations could abandon zero-sum thinking and turn their energies to cooperation as the basis of international peace.

“We believe that the safety of this nation—as opposed to its ability to inflict damage on an enemy power—cannot lie wholly or even primarily in its scientific or technical prowess,” penned my grandfather. “It can be based only on making future wars impossible.”

In one respect, that hope has been realized. Since 1945, there has not been another direct confrontation between great powers such as the two world wars. In another respect, we failed. We did not prevent the arms race, and we have lived under the shadow of nuclear armageddon for nearly eight decades. Every minute of every day, we live in a perpetual state of complete vulnerability to the psycho-emotional whims of the leaders of the nuclear weapons states who, by merely giving an order, can eradicate civilization as we know it. The level of cooperation that ended WWII, which the Interim Committee recommended be marshalled for atomic energy in 1945, has not been reached. Without it we are still in grave danger, particularly from the often forgotten but always present threat of nuclear war.

Despite our survival thus far, the latent danger from nuclear weapons remains. We must address and reduce the issue head-on.

That is why my family and I have made it our mission to keep driving toward the goals set out by Robert and the Interim Committee eight decades ago. In this moment of particular danger, we must remind the world that victory in a total war between great powers is impossible and that there is unparalleled value in cross-cultural engagement and international cooperation. We recognize this alone will not resolve all conflict, which is far too complex and context-specific for generalized solutions. Yet, this does not require us to maintain the illusion that a few more nuclear weapons—or even tanks and drones—will secure peace through military victory.

We believe nuclear energy can be a source of hope for international cooperation—not just weapons and fear. And we are not alone here. This belief is at the heart of the Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), the cornerstone document of global nuclear governance signed by 191 countries which enshrines an “inalienable right” to peaceful uses of nuclear energy for all parties, in exchange for reducing and eliminating nuclear weapons. The key question before us is whether our leaders will use this amazing technology to help solve our greatest challenges.

The nuclear renaissance is here. From powering the development of nations in the global south while lowering carbon emissions to potentially curing cancer through repurposing nuclear reactor waste, nuclear energy is already being used for peaceful purposes. However, we have not fully explored the peaceful potential of nuclear energy.

We can use atoms to power peace. We have done this before. From 1993 to 2013, creative diplomacy helped achieve nuclear disarmament and peaceful uses simultaneously through the Megatons to Megawatts program. Together, the United States and Russia collaborated to downblended fissionable material from 20,000 Soviet-era nuclear warheads that were used as reactor fuel at nuclear power plants in the United States. This program provided 10% of total U.S. electricity for two decades.

We can do better today. Here are three ways how:

First, rather than waiting for another Soviet-like collapse in the international environment to explore the untapped potential of nuclear energy, we must begin the process now. Our international financial institutions can support nuclear energy initiatives around the world, from financing “first-of-a-kind” reactor technology to marshalling funders for a developing country’s first reactor.

Second, private funders can do more. Throughout the last century, philanthropic giving from some of the wealthiest individuals in history has fueled technological and societal transformation. They have enabled groundbreaking research in academia and the nonprofit sector which has informed our understanding of nuclear risks, and have facilitated cross-cultural engagement to transcend geopolitical divides. To secure international peace tomorrow, we need to revitalize philanthropists and foundations who are willing to fund a new generation of innovative thinkers informed, but not bound, by the past who will help us to navigate the challenges of today.

And third, we can help avoid nuclear catastrophe and maximize global abundance by collaborating on the peaceful applications of nuclear energy. This is a degree of global benefit worth striving for at the highest levels of the governments who control the most weapons. We know nuclear superpowers such as the U.S., China and Russia do not and will not agree on everything. The three have a mutual interest to prevent nuclear annihilation together. It doesn’t require a perfect peace to begin the discussion about reducing nuclear threats and increasing abundance—it is something we must talk about despite the tensions and other conflicts—for our very survival.

If we choose, the same atom that once symbolized destruction can become the foundation for peace.

That was the vision in 1945. It can still be our future.