This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

James Dobson, once the most powerful tentpole of the Religious Right and a kingmaker for politicians professing faith, died Thursday, his family announced. The 89-year-old child psychologist transformed a corner of the conservative movement into a roaring political force that shaped the national conversation and became the de facto base of the modern Republican Party that embraced performative piety as a precondition for viability.

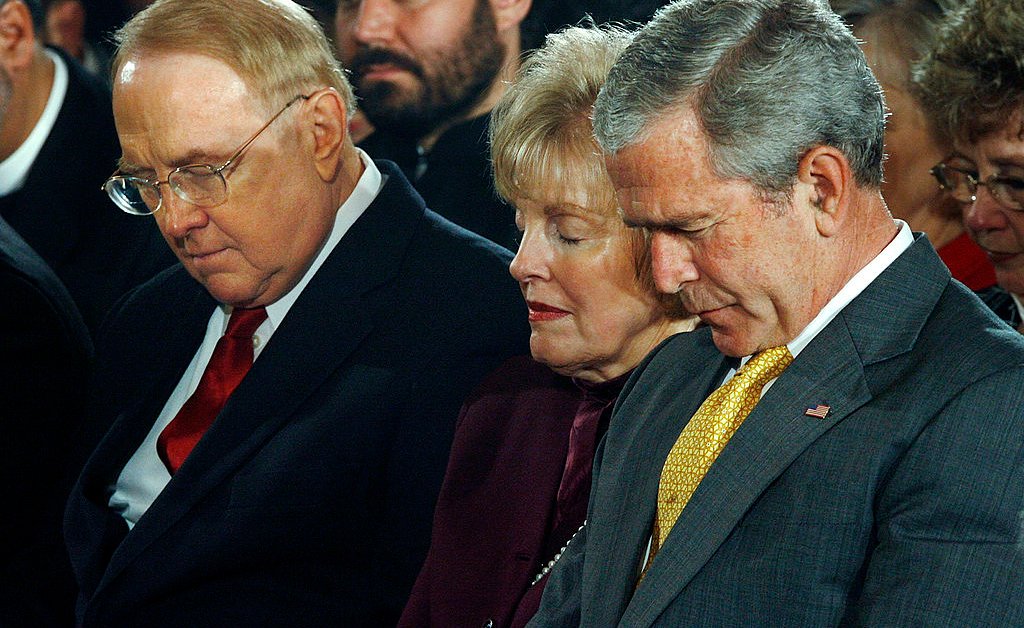

Dobson in his heyday was able to make or break political candidates, in part through two powerhouse groups he had a hand in creating: Focus on the Family and the Family Research Council. To those worried about an unchecked secularism, Dobson was a powerful agitator for his version of moral certitude and fundamentalist faith. His litmus test for candidates was a raft of so-called “pro-family” policy positions, such as opposition to abortion, same-sex marriage, and the teaching of evolution in public schools. The obvious successor to the political pulpit once owned by Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson, he was a media mogul who led a para-church empire that moved the Evangelical voting bloc onto a decidedly more political footing, one that helped the likes of George W. Bush carry swing states like Ohio and Florida by saying a non-vote was a sin. He later fell in line behind the thrice-married Donald Trump who no one confused for someone who spent much time in the pews. The politicization of Sunday mornings served Dobson’s aims but spiraled well beyond his original ambitions.

“Polls don’t measure right and wrong; voting according to the possibility of winning or losing can lead directly to the compromise of one’s principles,” Dobson wrote in 2007 at his height of celebrity. A decade later, he would find Jesus Christ in Trump’s nomination, defending support for the impious businessman by saying Trump was merely “a baby Christian.” He rationalized that even a flawed candidate who could pay conservatives lip-service—and give them like-minded judges—was still better than an avowed liberal who would protect the rights of religious and racial minorities.

Dobson’s passing comes as the current Republican Party has shifted away from its faith-grounded conservative impulses to one that is fighting culture wars based on grievance more than Gospel. Gone are the days when someone like Dwight D. Eisenhower, who did not join a church until after his election as President, could capture the GOP nomination. Now, Republican candidates trip over themselves in displays of public faith to kowtow to the hardcore base that sees the show as a substitute for substance. Dobson’s feverish crusades against pornography, gambling, divorce, and even SpongeBob SquarePants now seem almost quaint in a party that has fully embraced Trumpism.

Dobson’s role in making that transition from Ike to The Apprentice is tough to oversell. The group he led was designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center, a distinction that was brushed off as careless book-keeping. Dobson was one the nation’s most prominent opponents of same-sex marriage, a driving force that led him to back Bush’s re-election in 2004 and former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee’s bid in 2008. Dobson was among the religious leaders who decided to withhold support if either party nominated someone who backed abortion rights in 2008; only after John McCain picked Sarah Palin as his running mate did he move off the sidelines. “Winning the presidential election is vitally important, but not at the expense of what we hold most dear,” he said.

Months later, his group penned a missive that to this day retains its place among the most hyper-paranoid screeds in politics: envisioning, in the final days of the 2008 campaign, what the world would be like after a few years of Barack Obama as President, he described special bonuses for LGBTQ troops, porn taking over broadcast TV, an end to talk radio as we know it, an exile of home-schooling families to New Zealand, and conservatives jailed for their beliefs. “The Boy Scouts chose to disband rather than be forced to obey a Supreme Court decision that they would have to hire homosexual Scoutmasters and allow them to sleep in tents with young boys,” the letter warned in a hypothetical message from the future.

Although not an ordained minister, Dobson was clearly fluent in Evangelical phrasing and unwelcoming of greys. The Apocalypse was always just one election count away. His sermons against The Other sparked fear and fury, providing fertile ground for Trump’s brand of politics and plenty of fodder for critics who branded either of them as bigots. Usually speaking in absolutes, Dobson’s style did not allow for nuance and instead cast things in morally right and wrong. Even in semi-retirement, he kept up his campaign for his favored causes, including in support of Trump’s discredited effort to overturn the 2020 election results and against Kamala Harris’ bid for the White House four years later.

For a big chunk of the electorate, Dobson’s worldview was the truth and the light. As much as the Left tried to cast those views as antiquated and outrageous, they were nevertheless gospel to millions of Americans. In a country where every voter has a say, that means they cannot be ignored, even now that Dobson is dead. Like the notion of democracy itself, the ideology he preached is bigger than any one messenger.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.