Americans Are Now Even More Vulnerable To Online Romance Fraud

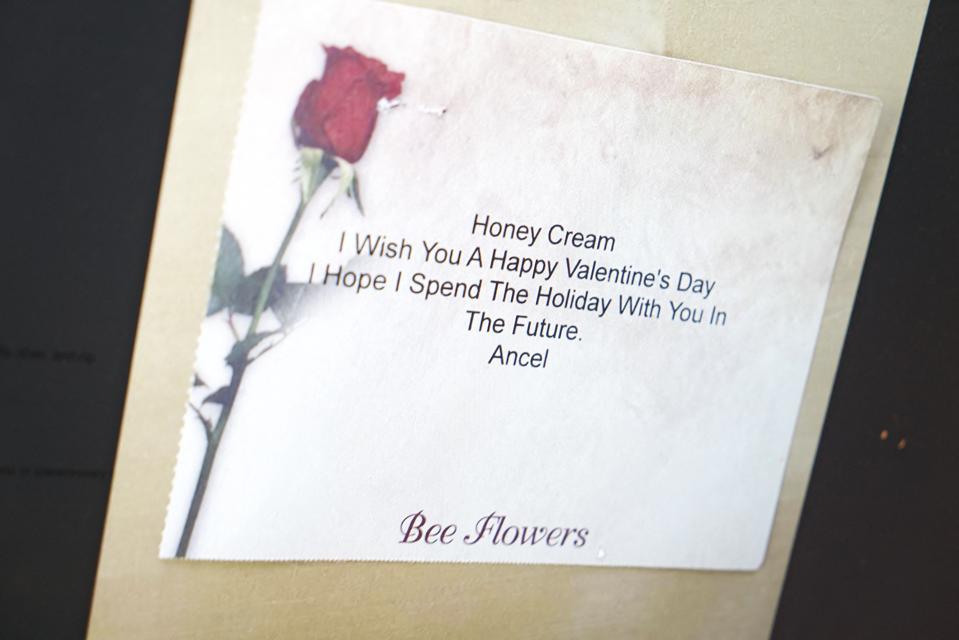

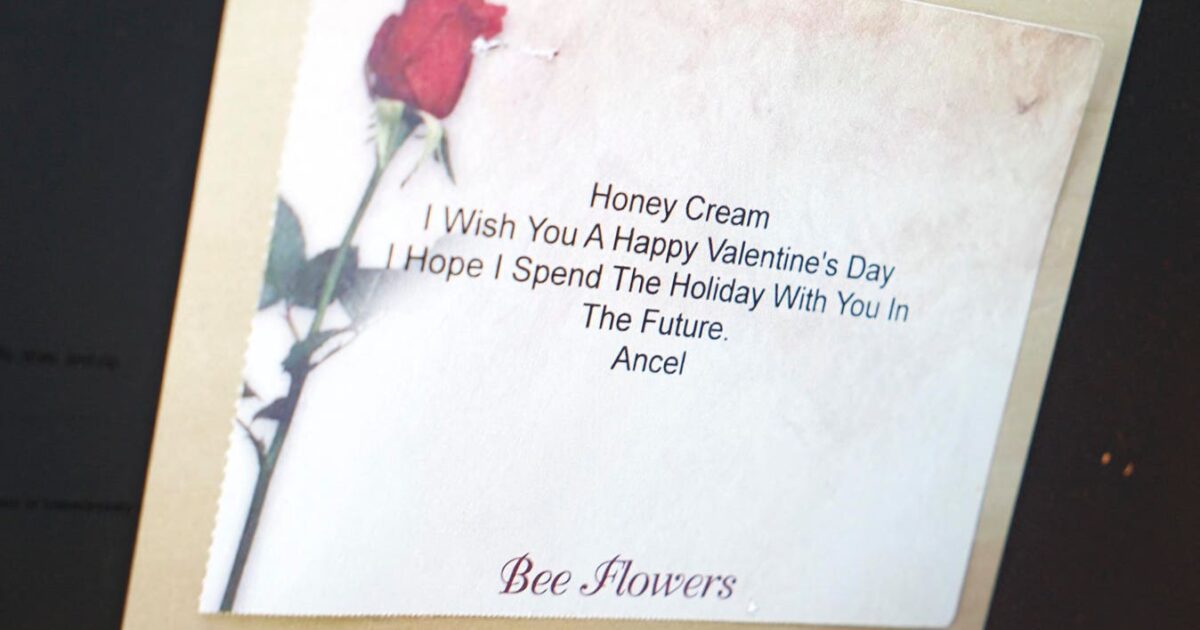

A Valentine’s Day card that a Philadelphia tech professional received from a romance fraudster, who took $450,000 from her (Photo by Bastien Inzaurralde/AFP via Getty Images)

AFP via Getty Images

In a U.S. Senate discussion in February, Cindy Dyer, the former ambassador-at-large to monitor and combat trafficking in persons, spoke forcefully about the links between trafficking abroad and victimization at home. Her office’s programs in Southeast Asia “were focused on addressing online scam operations that used trafficking victims to defraud Americans of millions of dollars. Frequently these were older Americans who lost their life savings,” Dyer explained. “Once Americans lose that money, that money is gone forever.”

In 2024, Dyer’s office collaborated with the Treasury Department and other agencies to sanction a Cambodian politician/entrepreneur whose companies had been luring in jobseekers under false premises and forcing them to work in scam centers, for up to 15 hours a day. The victims had had their passports and phones confiscated. They had been beaten and administered electric shocks if they sought help. For some victims, the only escape was suicide.

This is an example, Dyer told the senators regarding the cuts to foreign aid, of “how these edicts do exactly the opposite of what Trump and the administration say. They are making Americans less safe less prosperous and less secure.”

It’s impossible to produce exact numbers of this type of fraud, which frequently involves grooming or emotionally abusing targets into believing that they are in a genuine romantic relationship before starting to request money. Cyberfraud is a murky criminal world. And because victims are understandably nervous about revealing what happened to them, it’s massively underreported. “There’s a lot of stigma associated with being a victim of fraud,” notes John Breyault, the vice president for public policy, telecommunications and fraud at the National Consumers League (NCL), an advocacy organization. “And frankly, this [stigma]

is often something that the criminals themselves will try and latch on to using things like ‘Nobody will believe you if you tell them’…to try and keep people from talking about this or reporting it to the authorities.”

One estimate is that worldwide, one in four people have been scammed online. (This includes a variety of types of fraud, including romance fraud.) In the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission estimated that 2023 losses from all fraud, online and offline, and adjusted for underreporting, amounted to a staggering $158 billion dollars. Not million, $158 billion. When people aged 60+ were the targets, romance scams were the third most common category. Older Americans reported losing $277 million to romance scams in 2023. (The actual figure is likely to be much higher, due to underreporting.)

The NCL runs Fraud.org, a site where consumers can report and learn more about fraud, including “sweetheart swindles.” In most of the romance fraud cases the NCL encounters, the crimes are being perpetrated from overseas. “One of the reasons that these scams have become so pervasive is indeed because the perpetrators of them are located overseas, where they’re often out of the reach of U.S. law enforcement,” Breyault says. So international cooperation is important to addressing what is typically an international crime. Yet that kind of cooperation across borders has been impaired by the Trump administration’s foreign policy. “The consequence of America withdrawing from alliances and commitments overseas…has implications for our vulnerability to this very significant crime,” Breyault believes.

How U.S. Federal Cuts Affect Anti-Fraud Work

There can be blurred lines between victims and perpetrators. In fact, many people carrying out the fraud are actually victims themselves: people targeted with attractive and legitimate-sounding job offers, flown into foreign countries, and then forced into dangerous and emotionally difficult work defrauding others online.

When contacted for comment, the State Department declined to specify whether any anti-trafficking programs have survived the federal government’s rushed purge of most foreign aid programs. The remainder will now sit under the slimmed-down State Department. But throughout the last months of chipping away at the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), before doing away with it altogether, anti-trafficking organizations have reported a number of project cancellations and staff layoffs. This translates into the evaporation of funding to rescue and assist trafficked scam workers. The Trump administration is also trying to gut the United States Institute of Peace, a federally funded peacebuilding organization, whose research areas include cyberfraud in Southeast Asia.

Other federal cuts are contributing to the erosion of anti-fraud work. “Firings at some of the enforcement agencies are really, we fear, hollowing out the very professionals whose job it is to fight fraud,” says Breyault, referring to agencies including the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). “And so with fewer cops on the beat, we can anticipate that consumers are today more vulnerable to this crime than they were when President Trump took office on January 20th.”

Samady Ou, a human rights activist from Phnom Penh now living in California, has seen how the demise of USAID has affected efforts to protect people trafficked into Cambodia. USAID had funded safe housing in Thailand for Cambodian journalists reporting on human trafficking by cybercrime networks, for instance. Now reporters and dissidents are squeezed into slums and dependent on food donations, says Ou, a youth ambassador for the Khmer Movement for Democracy (KMD) and a freedom fellow with the Human Rights Foundation. “They are in hiding.”

Independent sources are vital to expose victimization within Cambodian scam compounds — these are essentially undeclared prison cities where many workers have been trafficked for the purpose of carrying out fraud. Within the country, Ou says, “mostly it’s being kept quiet.” Those who attempt to expose the corruption and abuses fuelling cyber slavery are at risk. Notably, Cambodian journalist Mech Dara, who was arrested in 2024 after reporting on scam compounds, has been forced to denounce his own reporting, and now spends his time growing vegetables. In March, the U.S. government cut off funding to Radio Free Asia, which Ou calls the only independent media left in Cambodia.

People are sounding the alarm from other parts of Southeast Asia too. “With the termination of our USAID-funded project, the number and scale of victimization in the USA could increase,” says Eugenio Gonzales, who managed a project called Strength CTIP for the Partnership for Development Assistance in the Philippines Inc. (PDAP). Strength CTIP, an abbreviation for Strengthening Local Systems and Partnership for More Effective Sustainable Counter-Trafficking in Persons, covered four Ps: prevention of trafficking, protection of victims, prosecution of perpetrators, and partnership with NGOs and different levels of governments.

Gonzales has been dealing with USAID in some form since 1991. “Even then, we were concerned about sustainability,” Gonzales reflects. “We had no illusions that foreign aid would be there forever.” Over the years Philippine counter-trafficking projects have found some ways to increase financial self-reliance, for instance by starting fair trade farming projects.

Still, this type of income generation can’t compare with the steep rise in internet-linked exploitation. So Gonzales and the partners depending on Strength CTIP, which was designed as a five-year project, were shocked by the abruptness with which the USAID funding was cut off earlier this year. Shelters for victims of trafficking have become squeezed. And counter-trafficking education projects “just disappeared. So the Philippine government is really hard pressed to reallocate funding for those kinds of projects.”

The Limits Of Individual Action

Large-scale action across borders is the only way to curb the rise in online romance fraud. But with fewer government resources for this activity, the burden will fall even more on individuals to stay vigilant.

There are some things to watch out for. One major red flag is an attempt by someone in a new relationship to isolate the other person from their friends and families. This can be a pre-emptive measure to deflect criticism of the relationship.

Indeed, the problem starts well before someone starts asking for money — which, for a romance fraudster playing the long game, might take months. At that point the person is already in too deep, explains Suleman Lazarus, a visiting fellow at the Mannheim Centre for Criminology, part of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). “Sometimes when it reaches the phase of money, it’s too late to stop,” Lazarus says. He advises people in new online relationships to share their experiences with family and friends right from the start. They can’t pick up on warning signs if they’re in the dark.

One worry is that fraudsters are becoming ever more sophisticated at targeting vulnerable people. “One common thread that runs through romance scams’ victims is they’re often people who have recently experienced some kind of loss or some kind of trauma, and they are looking for companionship,” Breyault explains. That applies to nearly all of us, at some point in our lives. But criminal networks can now easily identify individuals in specific situations of bereavement or divorce.

AI is helping to fine-tune lists of potential targets: for instance, American women over the age of 55 who have a certain amount of wealth and have recently lost a loved one. It’s no longer necessary to have a high degree of technological sophistication to obtain this very specific information, Breyault warns. It’s available for sale via criminal networks.

AI is also helping to smooth over awkwardness in language, which previously might have been a red flag that an attractive stranger claiming to be American or British was actually of a different nationality. As Breyault says, “With an AI, it’s much easier for someone overseas with limited English to make a convincing text message.” As well, AI can change accents.

Tech platforms hosting the posts of fraud networks could invest more in content moderation in order to disrupt the criminal business. But they’re unlikely to do so at anything like the scale required, unless regulators require this of them. And the current federal government has sought to loosen the reins on big tech companies, rather than tightening them.

Financial institutions could also do more to curb money laundering linked to online fraud. But unlike other countries, the U.S. does not require banks to reimburse fraud victims or to close accounts used to launder the proceeds of fraud. And cryptocurrency, where much of the fraud earnings is now circulating, is of course even less regulated.

All this points to the inherent limitations of leaving it to individuals to stop industrial-level transnational fraud. Gonzales says that one consequence of all the “confusion, contradiction and conflict” in U.S. development policy this year has been a hampered ability to fight scam hubs. “If you stop supporting projects that address the human trafficking for these kinds of hubs, the impact is you will have more Americans vulnerable to scams,” Gonzales warns.

This is the third in a series of articles about transnational romance fraud. The first article explores links between West Africa and the U.S. The second article focuses on connections between Southeast Asia and the U.S.