For one thing, the systems he imagines process data relatively slowly compared to those on terra firma. They’d be constantly bombarded by radiation, and “obsolescence would be a problem” because making repairs or upgrades would be confoundingly difficult. Hajimiri believes that data centers in space could, someday, be a viable solution but hesitates to say when that day might come. “Definitely it would be doable in a few years,” he said. “The question is how effective they would be, and how cost-effective they would become.”

The idea of simply putting data centers in orbit is not limited to the offhand musings of techies or the deeper thought of academics. Even some elected officials in cities where companies like Amazon hope to build data centers are raising the point. Tucson, Arizona, councilmember Nikki Lee waxed poetic about their potential during an August hearing, in which the council unanimously voted down a proposed data center in their city.

“A lot of people are saying data centers don’t belong in the desert,” Lee said. But “if this is truly a national priority,” then the focus must be on “putting federal research and development dollars into looking at data centers that will exist in space. And that may sound wild to you all and a little science fiction, but it’s actually happening.”

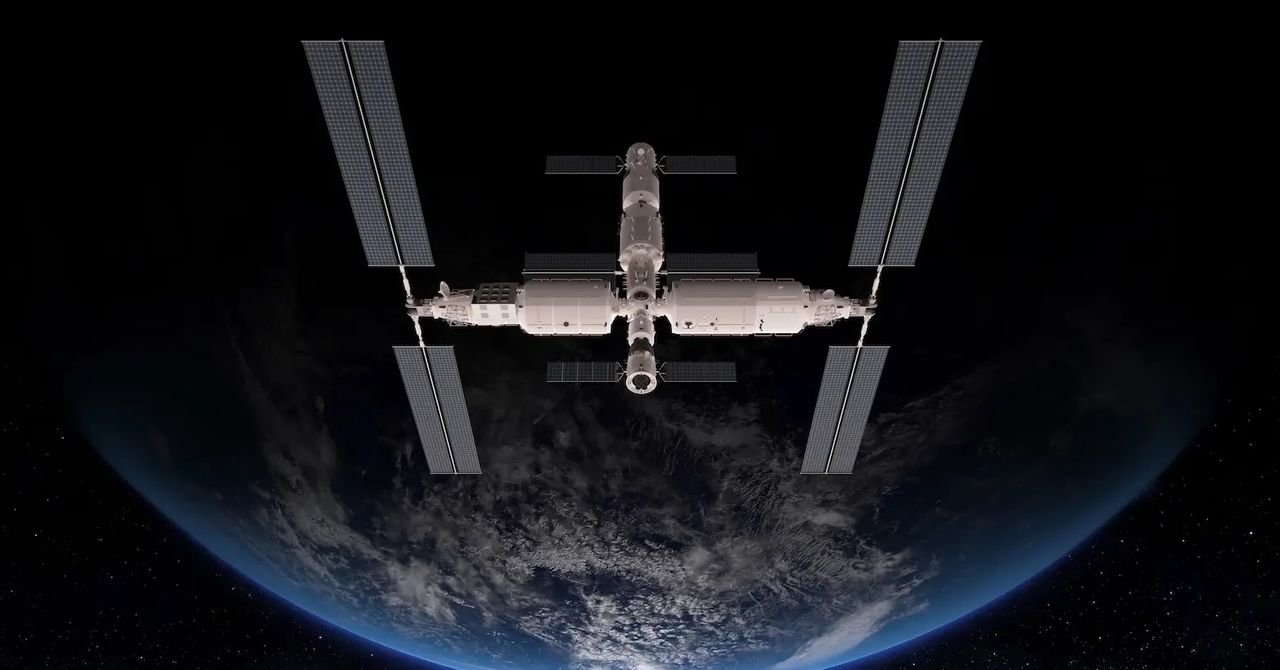

That’s true, but it’s happening on an experimental scale, not an industrial one. A startup called Starcloud hoped to launch a refrigerator-sized satellite housing a few Nvidia chips in August, but the launch date was pushed back. Lonestar Data Systems landed a miniature data center, carrying precious information like an Imagine Dragons song, on the moon a few months ago, though the lander tipped over and died in the attempt. More such launches are planned for the coming months. But it’s “very hard to predict how quickly this idea will become economically feasible,” said Matthew Weinzierl, a Harvard University economist who studies market forces in space. “Space-based data centers may well have some niche uses, such as for processing space-based data and providing national security capabilities,” he said. “To be a meaningful rival to terrestrial centers, however, they will need to compete on cost and service quality like anything else.”

For now, it’s much more expensive to put a data center in space than it is to put one in, say, Virginia’s Data Center Valley, where power demand could double in the next decade if left unregulated. And as long as staying on Earth remains cheaper, profit-motivated companies will favor terrestrial data-center expansion.

Still, there is one factor that might encourage OpenAI and others to look toward the heavens: There isn’t much regulation up there. Building data centers on Earth requires obtaining municipal permits, and companies can be stymied by local governments whose residents worry that data center development might siphon their water, raise their electricity bills, or overheat their planet. In space, there aren’t any neighbors to complain, said Michelle Hanlon, a political scientist and lawyer who leads the Center for Air and Space Law at the University of Mississippi. “If you are a US company seeking to put data centers in space, then the sooner the better, before Congress is like, ‘Oh, we need to regulate that.’”