In a recent Truth Social post, Donald Trump accused the Smithsonian of being “OUT OF CONTROL,” saying it focuses too much on America’s flaws, slavery, and racial injustice. There’s only one problem: a sanitized version of American greatness leaves little room for the truth about slavery and racial injustice. In other words, Trump’s preferred version of history is not America’s actual history.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

This impulse to suppress uncomfortable truths about slavery is not new. It is part of a long tradition in American politics, one that dates back to the nation’s founding and gained traction in the 1830s when Congress passed the infamous “gag rule,” banning the discussion of slavery on the House floor. Then, as now, the goal was not just to avoid conflict—it was to erase dissent and avoid a moral reckoning with slavery.

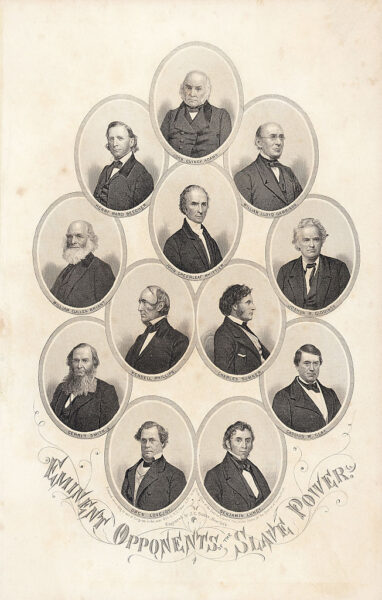

To understand what is at stake, we must revisit the original gag rule and the man who fought to overturn it: John Quincy Adams, America’s sixth president.

After losing reelection election to Andrew Jackson in 1828, Adams did something remarkable. Instead of retiring, he ran for Congress, and for the next 17 years, he was a relentless advocate for the right to petition the issue of slavery.

Read More: The History of Abolitionism Shows How One Person Can Help Spark a Movement

In the 1830s, constituent services did not exist, there were no local congressional offices, no email contact forms, and no staffers operating the phones. The best and only way an American citizen could “petition the government for a redress of grievances” was to send a petition to their representative, to be read on the floor of the House. Petitions would then be referred to the appropriate committee, entered into the record and printed, or, as was often the case, tabled.

By 1836, abolitionists’ petitions were arriving at the Capitol by the wagonload. Prayers for an end to slavery were signed by tens of thousands of citizens from the Northern states, many of whom were women galvanized by the evangelical fervor of the Second Great Awakening. Piles of petitions lined the hallways of Congress and overflowed from John Quincy Adams’ desk.

Enter Henry Laurens Pinckney, a South Carolina congressman who proposed a resolution to “lay upon the table” all petitions related to slavery—effectively silencing them. Adams was outraged. He demanded his voice (the voice of fellow Americans, his constituents) be heard and the resolution withdrawn. When Speaker of the House James K. Polk refused, Adams thundered, “I am aware there is a slaveholder in the chair!” The chamber erupted in chaos. Southern congressmen shouted him down. Polk refused to recognize him. Adams stood firm and asked, “Am I gagged, or am I not?”

The resolution passed. The gag rule was born. For the next eight years, even the mention of slavery on the House floor was forbidden. Adams fought tirelessly to overturn it, defending the First Amendment and the right to petition. Adams maintained that democracy depended on a citizen’s right to dissent. For his convictions, he received death threats and two attempts at censure.

But Adams never backed down. Using his encyclopedic knowledge of House rules and his deft rhetorical skills, Adams could spin any floor debate into one about the issue of slavery. For example, in a fiery defense of federal aid to the citizens of Alabama and Georgia devastated by recent Native American hostilities, Adams invoked Congress’s war powers, while calling attention to a deeper hypocrisy. If Congress could act in wartime to protect citizens, he argued, it could also emancipate the enslaved during a “servile war.” That logic shattered slaveholders’ claims that Congress lacked authority over slavery in the states and Washington, D.C.

Over the next decade, Adams’ defense of the right of petition deepened his kinship with abolitionists. Tensions over tactics emerged, however as Adams pushed back against their calls for immediate emancipation, seeing them unrealistic and irrational. It got to the point that abolitionists offered Adams commendations for his actions one day and condemnations the next.

In the late 1830s, as a devastating financial crisis bankrupted antislavery societies across the North, the movement seemed splintered and powerless to keep up its petition pressure campaign. But then a twist of fate in the form of a mutinous slave ship off the coast of the United States offered an opportunity to take the battle over slavery to the courts.

In 1841, John Quincy Adams stood before the Supreme Court and defended a group of enslaved captives who mutinied aboard the Spanish slave ship Amistad. Adams argued that the captives had the right of due process. “If the good offices of the government are to be rendered to the proprietors of shipping in distress, they are due to the Africans only, and the United States is now bound to restore the ship to the Africans and replace the Spaniards on board as prisoners.”

But Adams wasn’t there to make just a legal argument. He was also arguing for the soul of the nation. He had watched his parents, President John and First Lady Abigail Adams, and their generation create this nation. Now, it was up to his generation to preserve the moral ideals of its founders. Adams pointed to the Declaration of Independence hung on a pillar in the court. “The moment you come, to the Declaration of Independence, that every man has a right to life and liberty, an inalienable right, this case is decided. I ask nothing more in behalf of these unfortunate men, than this Declaration.” Perhaps the greatest testament to John Quincy Adams the man and sense of public service is that after delivering his closing arguments in the Supreme Court, he packed up his papers, walked upstairs, and took his seat at his desk in Congress to engage in the work before him there.

Adams’ argument prevailed, 7-1.

Associate justice Philip Barbour died over the course of closing arguments so the decision was left to the surviving eight justices, of which four slaveholders voted with the majority, leaving Justice Henry Baldwin, who there is no definitive proof owned enslaved persons but was an outspoken proslavery advocate, to dissent. Associate justice Joseph Story later wrote that Adams’ argument before the court was, “Extraordinary for its power, for its bitter sarcasm, and for its dealing with topics far beyond the record and points of discussion.”

Adams remained in the House of Representatives throughout the 1840s. By this time, Adams was joined in the House by new generation of Northern Congressmen who took up the fight against slavery. In 1847, this would include an awkward-looking, but well-spoken Whig Congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln.

Read More: Crushing Dissent is as American as Protest Itself

On Dec. 3, 1844, the gag rule finally met its doom in a vote of 108-80—a victory thanks in no small part to Adams’ tireless efforts over the previous eight years to marshal the rules and procedures of the House against the majority. Adams’ tactics rendered the gag rule toothless and useless, prompting even six southern Congressmen to vote in favor of overturning it.

But that was not the end of the gag rule. Long after John Quincy Adams passed away in 1848 (collapsing of a stroke while working at his desk in the Capitol), newer versions emerged—as Jim Crow laws, after the failure of Reconstruction in the 1870s, and later as the filibuster during the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century. Today, we can see it in the form of partisan gerrymandering that weakens the voting rights of minority communities.

In this new era of gag rule politics, some on the right have claimed that uncomfortable discussions about the history of slavery in the United States are meant to make white people feel bad about themselves—that whites today are somehow to blame. That’s not true.

Acknowledging the wrongs of the past does not make us the perpetrators of those wrongs. Reckoning with the worst chapters of our history means that we are a living testament to the aspirations of the Declaration of Independence, that we have the power to surrender to our better angels—just as John Quincy Adams routinely reminded his colleagues when his generation confronted the injustices some now wish to forget.

Bob Crawford is the author of the forthcoming book America’s Founding Son: John Quincy Adams, from President to Political Maverick and a founding member of the Grammy-nominated band The Avett Brothers.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.