Modern-day eagles are large birds, but they’re nowhere near the size of some extinct raptors. Here’s … More

There are over 60 species of eagles in existence today — some of which are massive by bird standards.

The Philippine eagle, for example, has an average weight of 18 pounds and measures over three feet from head to talon. The white-tailed eagle has the one of the largest wingspans, averaging seven feet and two inches.

Harpy eagles, Stellar’s sea eagles and wedge-tailed eagles are also among the biggest present-day raptors.

But to find the biggest known eagle, you’d have to search back to the 1400s, when the behemoth Haast’s eagle was still circling the skies of New Zealand. Here’s its story, and the reason why it went extinct.

Haast’s Eagle: From Aerial Dominance To Extinction

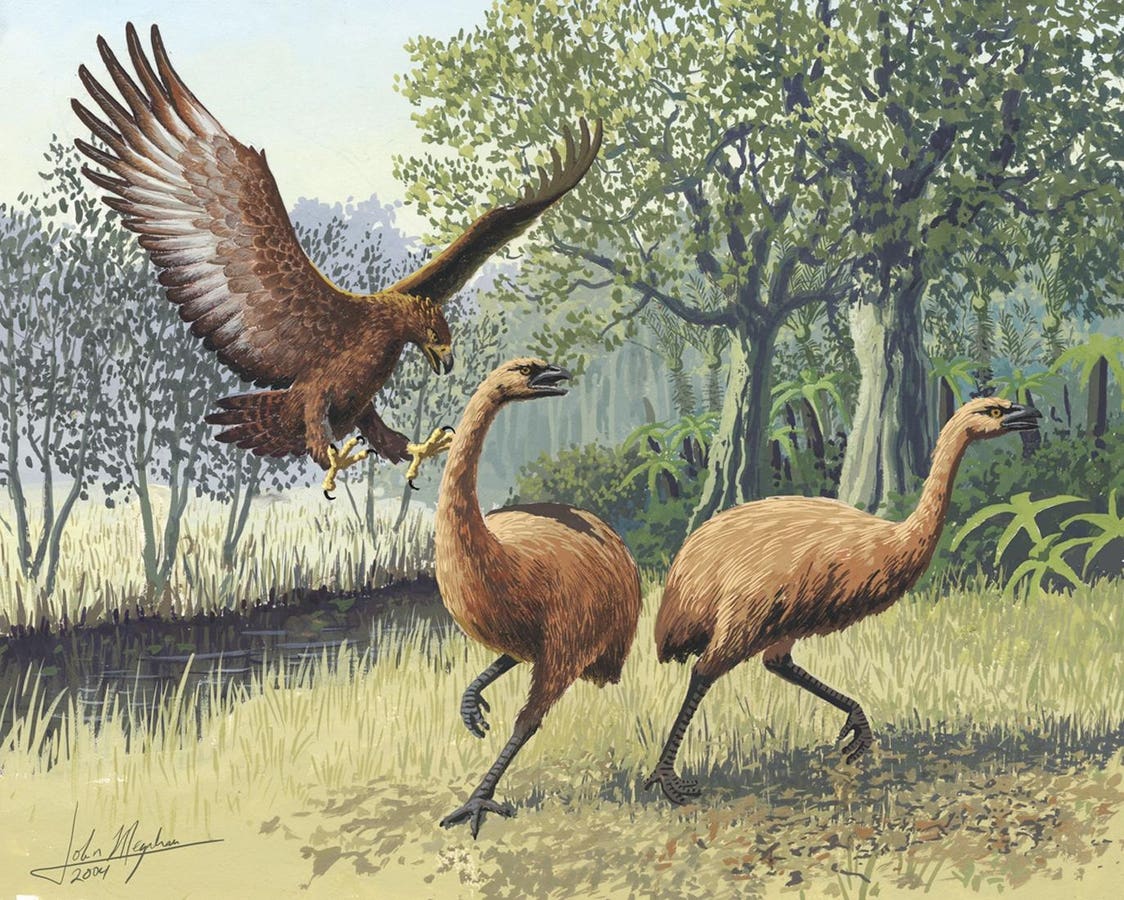

Weighing up to 33 pounds and boasting a wingspan of 8 to 10 feet, Haast’s eagle (Hieraaetus moorei) was not only the largest eagle to have ever lived, it was also one of the most formidable. Its massive talons were comparable in size to those of a tiger, and its powerful beak could pierce through thick muscle and bone.

Unlike many modern raptors that target smaller prey, Haast’s eagle hunted on a much larger scale. Its primary target? The moa — a giant flightless bird that could stand up to 12 feet tall and weigh more than 500 pounds.

(Sidebar: While extinctions of birds like the moa and Haast’s eagle were often unintended consequences of human activity, Australia once launched a deliberate campaign to wipe one out. See here to learn why the government declared war on the emu in 1932 — and lost.)

Haast’s eagle evolved in isolation on New Zealand, where it reigned as an apex predator in a land with no mammalian carnivores. The island’s unique ecosystem, free of natural eagle competitors and with an abundance of slow, ground-dwelling birds, gave Haast’s eagle the perfect conditions to grow to the size it did.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Haast’s eagle’s enormous size is what its ancestry reveals. While it was once thought to descend from Australia’s largest living eagle, the wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax), ancient DNA analysis told a different story. Haast’s eagle actually evolved from one of the world’s smallest eagles — Australia’s little eagle (Hieraaetus morphnoides), which weighs just two pounds. This dramatic transformation is among the most extreme cases of island gigantism in birds, likely unfolding in under two million years as the eagle adapted to New Zealand’s ecosystem.

Comparison of talon size between Haast’s eagle (top) and its closest living relative, the little … More

Given its massive size, researchers have long debated whether Haast’s eagle was an active predator or more of a scavenger, like vultures and condors. Current evidence favors the predator role — biomechanical studies suggest it could kill prey several times its own weight, striking with explosive force and subduing victims using its powerful talons. Though it hunted like a modern eagle, its feeding behavior likely resembled that of a vulture, tearing into large carcasses with techniques adapted for consuming animals far bigger than itself.

But in a land ruled by birds, this delicate ecological balance was not built to last. Even the most powerful predator can be vulnerable to sudden ecological change — and for Haast’s eagle, that change came swiftly with the arrival of humans.

Around the 13th century, Polynesian seafarers arrived in New Zealand, bringing with them fire, rats, dogs, and eventually the devastating impact of human hunting. The moa, never having known a predator like man, were hunted to extinction in less than two centuries. This was a catastrophic blow for Haast’s eagle, whose survival depended almost entirely on moa populations. Without its main food source, the eagle’s numbers plummeted. By the mid-1400s, it too had vanished.

Interestingly, Haast’s eagle played a significant role in early Māori culture. Oral traditions and ancient rock art describe a monstrous bird called the Pouakai or Hokioi — a giant creature capable of killing humans and carrying them away. Given the eagle’s size, strength, and hunting behavior, many scientists now believe that these stories were based on real encounters with Haast’s eagle before it went extinct.

Today, all that remains of this apex raptor are fossilized bones and stories, pieced together by biologists, anthropologists, and paleontologists.

Does thinking about the extinction of a species instantly change your mood? Take the Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension.