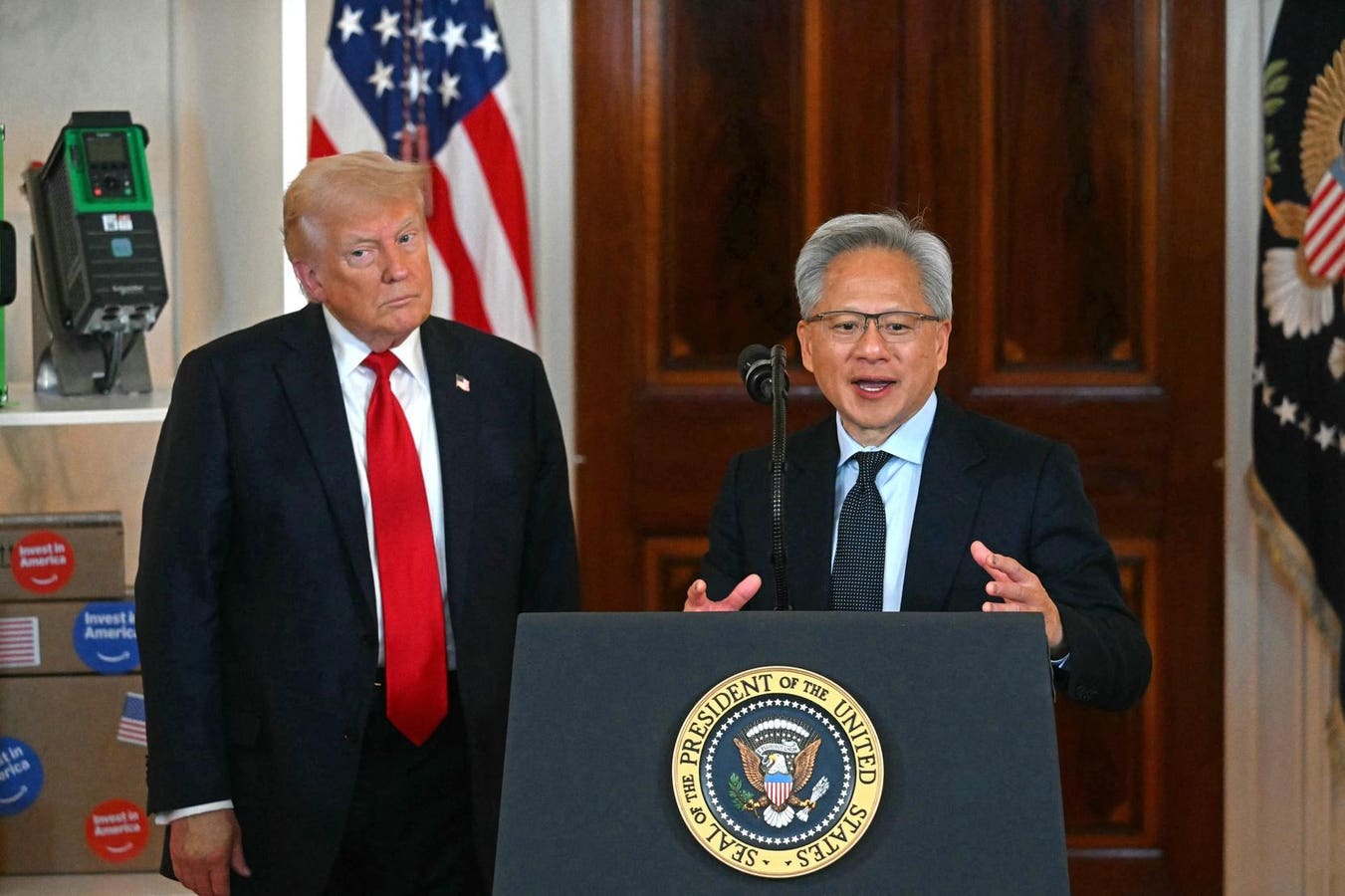

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang speaks alongside U.S. President Donald Trump at the White House in April … More

U.S. export policy around advanced semiconductors — particularly Nvidia’s H20 and Blackwell-class AI chips — has created a growing debate about how to balance national security and economic competitiveness. None of this is new to me, as I dealt with export controls during my time at AMD and have written about earlier export restrictions placed on Nvidia by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security. (Note that Nvidia is an advisory client of my firm, Moor Insights & Strategy.)

In short, I support allowing Nvidia to sell the H20 and future de-tuned Blackwell variants directly to China for non-military use. Further, I support allowing full-featured Blackwells to be exported for datacenters in the Middle East owned by non-Chinese cloud service providers, starting with AWS, Microsoft, Google and Oracle, as well as vendors of on-prem equipment like Dell Technologies, Cisco, HPE and Lenovo when outfitting smaller CSPs. This infrastructure should be eligible for use even by Chinese civilian customers. All of this should be carried out under strict know-your-customer protocols.

I believe this position balances the need to limit military AI proliferation by China while avoiding self-defeating protectionism that erodes American market leadership and accelerates Chinese alternatives. I’ve publicly said that it’s better to sell chips with strict controls than to sit back and watch Huawei take market share. History shows Huawei’s ability to become a juggernaut across different areas of tech — witness its 30% share of the global market for carrier networking equipment. If we continue down the path of maximum restriction, we risk enabling Huawei to build its own AI “Belt and Road” in Asia and beyond. By contrast, letting Nvidia compete under reasonable safeguards would ensure that American standards — not Chinese ones — define the next wave of global AI.

Background: U.S. Export Controls And The H20 GPU

The Biden Administration imposed sweeping restrictions on AI chip exports to China through regulatory frameworks such as the October 7, 2022 Commerce Department rule and the follow-up interim final rule of October 17, 2023. The Biden Administration added worldwide controls in the January 2025 framework known as the “AI Diffusion Rule.” These rules defined performance thresholds that covered products such as Nvidia’s A100, launched in 2020, and were intended to limit proliferation of frontier AI hardware. Nvidia’s H100, H200 and other advanced GPUs were blocked, but the H20 was designed to comply with the new rules with plenty of room to spare — falling well within the thresholds of the BIS “green zone” and thus not requiring a license or notice before shipping. While critics argue that this is a loophole, the rules were designed to encourage sales of green-zone products like the H20. In December 2023, Biden’s Commerce Secretary, Gina Raimondo, stated that Nvidia “can, will and should sell AI chips” such as the H20 — while reserving the highest-performing products for the U.S. and its allies.

After a slow start, H20 sales gradually picked up, because the product is a workhorse for workloads such as recommender systems, consumer internet and chatbots. Earlier this year, however, the Trump Administration froze further sales of the H20 through a process called an “is informed” letter — not a regulation — instructing Nvidia to halt until further notice.

In the wake of the U.S.–China trade and export negotiations of the past few months, the Trump Administration has indicated that H20 sales can resume, subject to notice and license requirements. The new policy is still much more strict than the Biden Administration’s — which allowed sales without any notice — but it will allow Nvidia to compete on the ground with China’s national champion, Huawei.

Criticism Of Nvidia Exports — Versus The Reality I See

Some China trade hawks argue against allowing H20 sales to China or enabling CSPs or other vendors to serve Chinese clients with cutting-edge AI compute in the cloud. The claim is that China may obtain enough H20s to support the development of multiple AI superclusters. Other arguments hold that the current export framework is too flimsy, making enforcement difficult, or suggesting that it’s bad (i.e., low-margin) business for Nvidia while simultaneously strengthening Huawei’s domestic alternatives.

But the concern that U.S.-designed chips may end up supporting Chinese military ambitions overlooks China’s own immense stockpile of AI chips (such as the Huawei Ascend) and the control mechanisms already available through cloud service providers or even the vendors for non-cloud superclusters required to create a leading-edge AGI frontier model. Because they are low-powered enough to operate in the BIS “green zone,” H20s are already available to CSPs in China — as they should be to keep those Chinese companies happily using U.S. technology. Meanwhile, civilian use of more advanced GPUs is both separable and traceable when routed through CSPs or vendors for on-premises or private-cloud infrastructure or smaller CSPs — based in the U.S. or allied nations — that operate under strict KYC requirements. For example, these protocols already enable U.S. cloud infrastructure providers to serve Chinese customers from U.S.-based datacenters, making the same approach feasible for deployments in the Middle East or elsewhere. Other mechanisms, such as U.S.-provided and -approved operating system software, or U.S.-provided service and support, can provide reasonable assurances as well.

Further, claims about weak enforcement fail to acknowledge the physical and operational security present in the Gulf region. Data campuses in places like the UAE — such as the planned 5-gigawatt AI campus — are hardened, auditable, and have well-developed telemetry systems that enable real-time visibility into GPU workloads. This makes diversion significantly harder than assumed. Five years ago, the fungible matter in question was a card; now it is a complete rack in Nvidia’s new B300 world.

As for the “bad business for Nvidia” part, it’s important to recognize that even low-margin volume helps sustain Nvidia’s manufacturing scale, and finances the R&D pipeline that drives U.S. leadership in AI. I also believe the newest Blackwell derivative for the China market will have a better cost basis due to its memory architecture. Starving U.S. companies — and not just Nvidia — of addressable markets only weakens the broader national-security and economic foundations they support. And every yuan of AI spending that goes to Nvidia is a yuan that doesn’t go to Huawei to reinvest into R&D, create better AGI sooner and spread it around the world — as it successfully did with its equipment for the telecom market.

The KYC-Controlled Export Model

The UAE and Saudi Arabia, which are key players in proposed GPU deployments, have no incentive to smuggle chips — they are resource-rich nations focused on energy exports, not illicit trade in AI hardware. Moreover, U.S.-based operators such as Microsoft and Amazon, even when deploying infrastructure abroad, still fall under U.S. export enforcement jurisdictions. The logistical difficulty of smuggling datacenter-grade hardware is often underestimated; these GPUs arrive preassembled into racks that can weigh over 3,600 pounds, making physical diversion highly impractical.

David Sacks, the Trump Administration’s AI and crypto czar, made some good points when he said on his All-In podcast, “Just look at market share. If we have like 80 to 90% market share, that’s winning. . . . If (China) has 80% market share, then we’re in big trouble.”

This framework can ensure that Chinese customers that access compute through Middle Eastern CSPs do so for civilian purposes only: e-commerce, LLM inference, logistics and so on. With military or frontier model training barred effectively, such usage does not create a meaningful national security threat, in my opinion.

Strategic And Economic Considerations

One major consideration is the potential for Huawei to dominate AI infrastructure across the Belt and Road Initiative countries if the U.S. restricts Nvidia’s ability to compete. The Ascend AI stack — Huawei’s response to Nvidia’s CUDA stack — is maturing rapidly. Blocking U.S. exports will unintentionally provide Huawei with captive market share in the Gulf region and South America, thereby accelerating its learning curve and scale.

Second, diffusion of American AI hardware, software, and frameworks is how the U.S. has historically maintained technological supremacy. Broad adoption of U.S. technology such as CUDA makes it difficult for alternative ecosystems to take hold. In that sense, the CUDA software stack is not just a performance accelerator — it’s a strategic lever. Widespread diffusion of Nvidia’s technology means technology lock-in that benefits U.S. interests.

Another underappreciated factor is mutual dependency. While the U.S. continues to rely on Chinese rare earths and materials, China remains reliant on Nvidia’s hardware and software stack. Chinese enterprises overwhelmingly prefer U.S. chips over domestic alternatives, when they can get them, due to performance and software maturity. Accelerating the decoupling of supply chains by denying access to Nvidia exports may ultimately backfire by pushing China toward full self-sufficiency.

Policy Recommendations

Rather than blanket bans, U.S. policy makers should implement targeted measures that mitigate risk without ceding strategic advantage. H20 sales to China should resume, subject to the licensing regime the Trump Administration has adopted. Blackwell GPU exports should be permitted to CSPs from the U.S. or allied nations operating facilities in the Middle East that serve Chinese civilian clients under rigorous KYC mechanisms — or with other safeguards acceptable to BIS, which can enable safe and secure on-prem and private cloud deployments as well. Large systems of concern can maintain detailed telemetry, usage logs and auditable records accessible to U.S. regulators.

Export licenses should clearly define prohibited end uses, including military and sensitive non-military applications, along with intelligence-related activities. More generally, national security should be redefined to include market share as a metric — because if the U.S. controls the global AI stack, it inherently retains strategic leverage.

Finally, the United States should collaborate with allies to formalize a global KYC enforcement regime for AI, harmonizing standards to prevent backdoor access and creating collective strength in export compliance.

Compete With Common-Sense Restrictions, Don’t Concede Global Market Share To China

U.S. leadership in semiconductors and AI has always been driven by innovation and market scale. Choking off the global market — particularly in regions aligned with U.S. interests — only serves to isolate Nvidia (and other American companies) and subsidize Huawei. China’s AI ambitions will continue regardless of U.S. policy. The question is: will they use American technology, or their own? By selling Nvidia solutions to China, can the U.S. get to AGI first? It seems to me that the U.S. government would want that.

With CSP-mediated controls, telemetry audits, and export compliance frameworks, I believe we can thread the needle — preventing diversion of cutting-edge AI technology while retaining global relevance. Blocking H20 from China or blocking Blackwell from even CSP-mediated delivery into China-aligned regions would be a strategic mistake.

We should lead by selling, not retreating.

Moor Insights & Strategy provides or has provided paid services to technology companies, like all tech industry research and analyst firms. These services include research, analysis, advising, consulting, benchmarking, acquisition matchmaking and video and speaking sponsorships. Of the companies mentioned in this article, Moor Insights & Strategy currently has (or has had) a paid business relationship with AMD, AWS, Cisco, Dell Technologies, Google, HPE, Microsoft and Nvidia.