AI branding evolution

CoreWeave, the first AI startup to go public, disappointed investors, ending its first day of trading with a market cap of $19 billion. The last time it raised funds as a private company, in May 2024, it was already valued at $19 billion, nearly triple its valuation just five months prior. The AI bubble may burst soon, followed by a period of reassessment and reckoning, and then the emergence of productive AI-based business practices and AI companies that make money rather than lose it by providing valuable products and services to businesses and consumers. We went through this validation process a quarter century ago, with the deflating of the dot-com balloon.

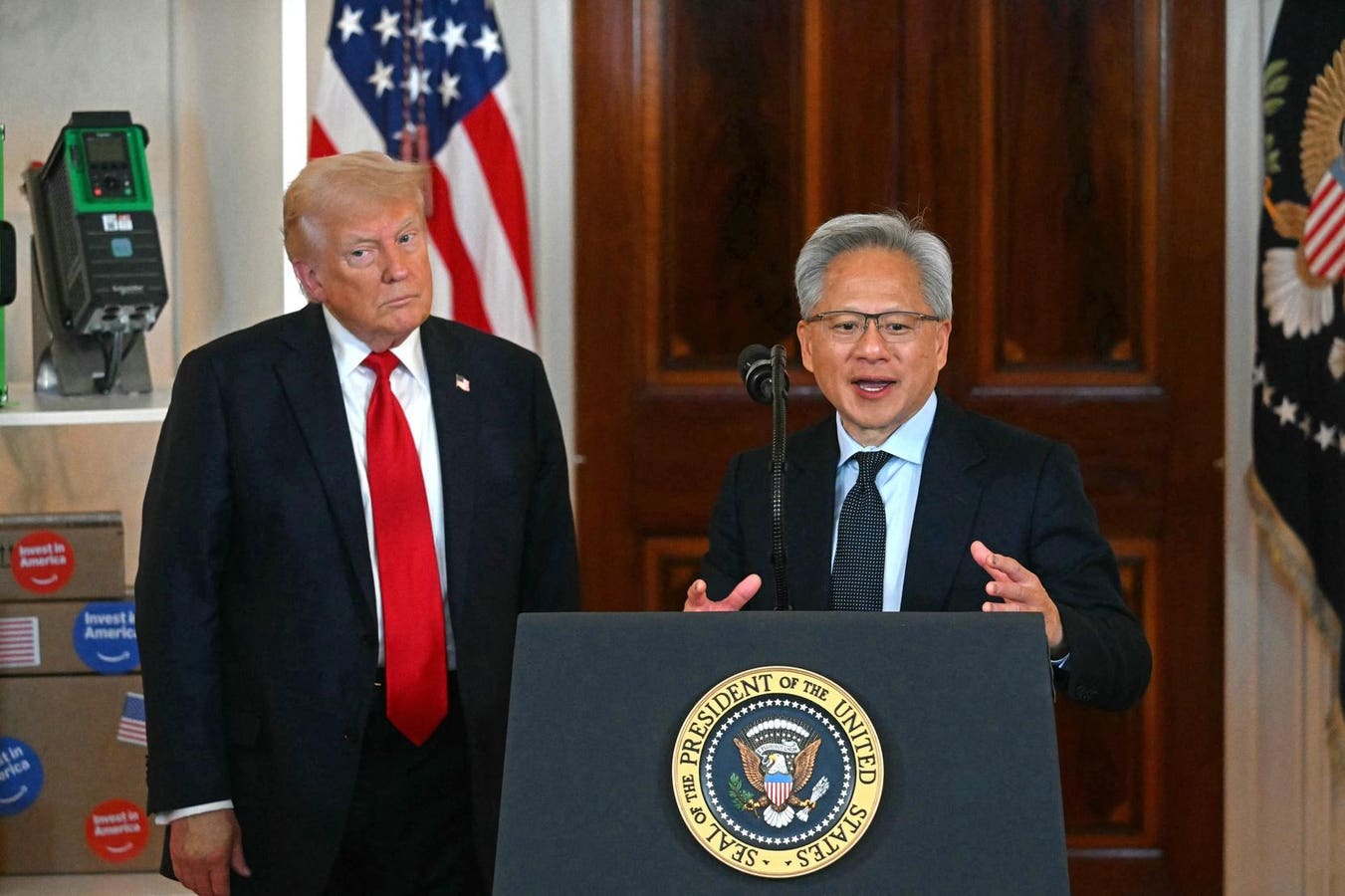

In January, the “DeepSeek Moment” pushed the AI bubble to the brink of a noisy blowout. U.S.-based AI entrepreneurs reacted to the sudden emergence of a Chinese low-cost and capable competitor by moving up their predictions of the imminent arrival of AGI or “superintelligence” and doubling down on exaggerated promises of AI’s near-future colossal business impact. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei, for example, in addition to calling U.S. export controls on chips to China “even more existentially important” than they were before, predicted that “In 12 months, we may be in a world where AI is writing essentially all of the code.” Goodbye millions of programmers, hello gigantic business savings.

However, according to Wired’s Steven Levy, who was given access to internal Anthropic meetings, Amodei argues that getting to the AGI finish line is far more important than saving money. As soon as next year, Anthropic and others may produce machines that will “outsmart Nobel Prize winners.” Millions of these AGIs will work together: “Imagine an entire nation of geniuses in a data center! Bye-bye cancer, infectious diseases, depression; hello lifespans of up to 1,200 years.”

Imagine, indeed. Humans can imagine “all the people, living life in peace” or “machines of loving grace” solving everything, allowing us to live for 1,200 years (why stop there?). Human imagination also produces highly successful marketing campaigns, such as “artificial intelligence or AI,” launched in 1955, and “Artificial General Intelligence or AGI,” launched in 2007.

These marketing campaigns mask the historical reality of “artificial intelligence,” the steady expansion of the capabilities and functionality of modern computers. In A New History of Modern Computing, Thomas Haigh and Paul E. Ceruzzi trace the transformation of computing from scientific calculations to administrative assistance to personal appliances to a communications medium. Starting with a “superintelligence” calculator surpassing humans in speed and complexity eighty years ago, this constant reinvention continues with today’s “AI,” the perfect storm of GPUs, statistical analysis models, and big data, adding content analysis and processing (not content “generation”) to what a computer can do.

This evolution has been punctuated by peaks of inflated expectations, troughs of disillusionment, and plateaus of productivity. It has been defined by various marketing campaigns and by specific “moments” describing a new stage of where computing is done and its impact on how we live and work.

The first such milestone, the IT moment, highlighted the shift from scientific calculations to business use. In 1958, Harold Leavitt and Thomas Whisler published “Management in the 1980s” in the Harvard Business Review, inventing the term “Information Technology.” Stating that “over the last decade, a new technology has begun to take hold in American business, one so new that its significance is still difficult to evaluate,” they predicted IT “will challenge many long-established practices and doctrines.”

Leavitt and Whisler described three major IT components. The first described what they observed at the time—high-speed computers processing large amounts of information. The second was just emerging—the application of statistical and mathematical methods to decision-making problems. The third was a prediction based on the authority of leading contemporary AI researchers—the “simulation of higher-order thinking through computer programs,” including programming “much of the top job before too many decades have passed.”

The focus of the article was on the organizational implications of this new technology, such as the centralization (or recentralization) of authority and decision-making facilitated by IT and IT’s negative impact on the job of the middle manager. While the pros and cons of “automation” continued to be debated in the following years, the main topic of discussion, admiration, and trepidation, was the constantly increasing speed of the modern computer and its implications for new computing devices and their applications.

The idea of constantly increasing speed as the key driver of modern computing was captured by Gordon E. Moore in “Cramming more components onto integrated circuits,” published in Electronics in 1965, predicting that the number of components that could be placed on a chip would double every year, doubling the speed of computers. It was a very specific prediction, couched in quantitative, “scientific” terms, with the convincing appearance of a law of nature.

“Moore’s Law,” as this prediction came to be known, is not about physics, not even about economics. And it is much more than a self-fulfilling prophecy guiding an industry as it is generally perceived to be. Moore’s Law is a marketing campaign promoting a specific way of designing computer chips, selling this innovation to investors, potential customers, and future employees.

Moore told Jeffrey Zygmont in 2001: “When we tried to sell these things, we did not run into a receptive audience.” Writes Zygmont in Microchip: An Idea, Its Genesis, And The Revolution It Created: “[by 1965], under assault by competing approaches to circuit miniaturization, feeling their product poorly appreciated, IC advocates felt a competitive urgency to popularize the concept. Therefore, they proselytized… [Moore’s] prophecy was desperate propaganda.”

Like other marketing slogans—and unlike the laws of physics—Moore’s Law was revised to fit with evolving market realities. In a 2006 article in the IEEE Annuals of the History of Computing, Ethan Mollick has convincingly showed that the “law” was adjusted periodically in response to changing competitive conditions (e.g., the rise of the Japanese semiconductor industry): “The semiconductor industry has undergone dramatic transformations over the past 40 years, rendering irrelevant many of the original assumptions embodied in Moore’s Law. These changes in the nature of the industry have coincided with periodic revisions of the law, so that when the semiconductor market evolved, the law evolved with it.”

As the power and miniaturization of computers steadily advanced, another milestone arrived: the networking moment. In 1973, Bob Metcalfe and David Boggs invented Ethernet and implemented the first local-area network or LAN at Xerox Parc. Metcalfe explained later that what became known as “Metcalfe’s Law” is a “vision thing.” It helped him jump over a big hurdle: The first Ethernet card Metcalfe sold went for $5000 in 1980 and he used the “law” to “convince early Ethernet adopters to try LANs large enough to exhibit network effects,” in effect promising them that the value of their investment will grow as more people get connected to the office network.

Metcalfe law—the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of its users—encapsulates a brilliant marketing concept, engineered to get early adopters—and more important, their accountants—over the difficulty of calculating the ROI for a new, expensive, unproven technology. It provided the ultimate promise: This technology gets more “valuable” the more you invest in it.

The networking moment made scale—how many people and devices are connected—even more important than speed—how fast is the processing of data. Together with the PC moment (1982) and the internet moment (1993) and the mobile moment (2007), it begat Big Data and today’s version of AI. It also turned into the rallying cry of an energized Silicon Valley—”At Scale” becoming the guiding light of internet startups. And it also led to yet another marketing campaign—the one about the “new economy”—and to the dot-com bubble.

In 2006, IEEE Spectrum published “Metcalfe’s Law is Wrong.” Its authors convincingly corrected Metcalfe’s mathematical formulation of network effects: “…for a small but rapidly growing network, it may be a decent approximation for a while,” said one of the authors in 2023. “But our correction applies after you hit scale.”

The IEEE Spectrum published my response to the article, which started with the following: “Asking whether Metcalfe’s Law is right or wrong is like asking whether ‘reach out and touch someone’ is right or wrong. A successful marketing slogan is a promise, not a verifiable empirical statement. Metcalfe’s Law – and Moore’s – proved only one thing: Engineers, or more generally, entrepreneurs, are the best marketers.”

Moore’s and Metcalfe’s “laws” are two prominent examples of the remarkable marriage of engineering and marketing ingenuity that has made many American entrepreneurs successful. However, the most successful marketing and branding campaign invented by an engineer (John McCarthy) has been promoting “artificial intelligence” since 1955. Today’s entrepreneurs, asking for billions of dollars of venture capital and seeking to distinguish what they develop from the somewhat tarnished image of old-fashioned AI, are promoting the new AGI campaign, promising to finally deliver what’s been promised many times in the past.

By doing so, they obscure the true distinction between what they have achieved and the various approaches taken in the 1950s (and later) to achieving computers’ “simulation of higher-order thinking.” Most importantly, they mislead the public with this disinformation campaign, diverting attention from the potential impact of their machine learning models on how we work.

Researchers and business executives not occupied with raising billions of dollars have started to provide empirical indicators of the organizational implications of AI, similar to what was captured by the IT moment of 1958. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial of the use of AI by 776 professionals at Procter and Gamble, found that “AI effectively replicated the performance benefits of having a human teammate—one person with AI could match what previously required two-person collaboration,” reports Ethan Mollick.

As a professor at the Wharton Business School (and author of a popular guide to the new AI), Mollick is sensitive to the real-world impact of AI on how work is done in organizations: “AI sometimes functions more like a teammate than a tool… The most exciting implication may be that AI doesn’t just automate existing tasks, it changes how we can think about work itself. The future of work isn’t just about individuals adapting to AI, it’s about organizations reimagining the fundamental nature of teamwork and management structures themselves.”

To paraphrase a re-engineering guru of the 1990s, don’t automate; recreate with AI. We may be arriving at a new milestone, the AI moment, with new, empirically validated insights into new ways to refashion the organization of work. We may also have arrived at the peak of the AI bubble, or it may still have a year or two before deflation. A very safe prediction, however, is that the marketing campaign about creating superintelligence will never expire.

Much has been said, in the U.S. and China, about how DeepSeek is a prime example of Chinese engineering prowess and focus on efficiency. I would venture to guess that success in the “AI race,” if there is one, would also be determined by marketing creativity. I ended my 2006 letter to the IEEE Spectrum with the following: “I would like to offer a new law, the Marketing Law, to the future Indian Moores and Chinese Metcalfes: The success of your idea will be proportional to the square root of the number of people repeating after you ‘two plus two equal five.’”