The federal government’s Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program is not operating, despite Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s claims that it’s being funded.

The program’s 26 staffers were placed on administrative leave in April, with terminations set for June 2, as part of a broader restructuring of federal agencies within HHS.

To date, none of the staffers have been reinstated, with layoffs set to take effect in less than two weeks, said Erik Svendsen, director of the Division of Environmental Health Science and Practice, a department within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that includes the childhood lead program.

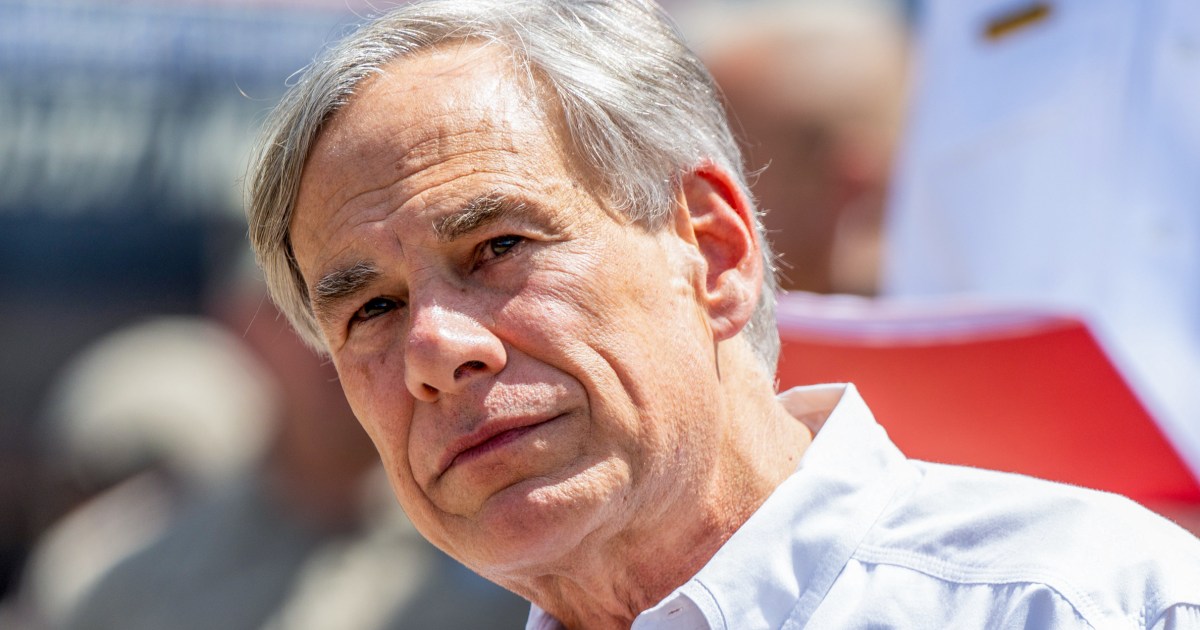

Kennedy had faced criticism in recent weeks from Democratic senators over the gutting of the program, which assisted state and local health departments with blood lead testing and surveillance.

At a hearing before the Senate Appropriations Committee on Tuesday, Kennedy told Sen. Jack Reed, D-R.I., that the program was still being funded. The week before, he told Sen. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., that he had no plans to eliminate it.

But Svendsen said his entire division was dissolved by HHS and can’t be easily replaced.

“There are no other experts that do what we do,” he said. “You can’t just push a button and get new people because our areas of public health are so specialized.”

Staffers in the childhood lead program have not received direction about how to transition their work, according to two CDC scientists familiar with the matter.

Even low levels of lead exposure could put children at risk of developmental delays, learning difficulties and behavioral issues. The CDC program offered technical expertise to help under-resourced health departments prevent those outcomes. In 2023, it helped solve a nationwide lead poisoning outbreak linked to cinnamon applesauce. And it was in frequent contact with the Milwaukee Health Department this year after the city discovered dangerous lead levels in some public schools.

Kennedy told Reed on Tuesday that “we have a team in Milwaukee” offering laboratory and analytics support to the health department.

But the Milwaukee Health Department said that Kennedy’s statement was inaccurate, and that the city had not received any federal epidemiological or analytical support related to the lead crisis.

“Unfortunately, in this case, that is another example where the secretary doesn’t have his facts straight,” said Mike Totoraitis, the city’s health commissioner.

Caroline Reinwald, a spokesperson for the Milwaukee Health Department, said that the federal government’s only recent involvement in the lead crisis was “a short, two-week visit from a single CDC staff member this month, who assisted with the validation of a new instrument in our laboratory.”

“This support was requested independently of the [Milwaukee Public Schools] crisis and was part of a separate, pre-existing need to expand our lab’s long-term capacity for lead testing,” Reinwald said in a statement.

The Department of Health and Human Services has said it will continue efforts to eliminate childhood lead poisoning through a newly created department called the Administration for a Healthy America. But Democratic lawmakers and environmental health groups question how the work can continue without reinstating staffers.

“Despite what you told me last week, that you have no intention of eliminating this program, you fired the entire office responsible for carrying it out,” Baldwin told Kennedy at Tuesday’s hearing. “Your decision to fire staff and eliminate offices is endangering children, including thousands of children in Milwaukee.”

HHS did not respond to a request for comment.

Kennedy did not offer new details about his agency’s restructuring plan at the hearing, citing a court order that compelled the Trump administration to pause efforts to downsize the federal government.

Milwaukee’s lead crisis became clear to health officials in February, when the city’s health department identified dangerous levels of the toxin in school classrooms, hallways and common areas, due to lead dust and deteriorating lead-based paint.

Before the childhood lead program was gutted, the CDC had been meeting with the Milwaukee Health Department on a weekly basis to come up with a plan to screen tens of thousands of students for lead poisoning, Totoraitis said.

The city’s health department asked the CDC on March 26 to send staffers to help, Totoraitis said, but the agency fired its childhood lead team on April 1 and denied Milwaukee’s request two days later.

“This is the first time in at least 75 years that the CDC has ever denied an Epi-Aid request, so it’s a pretty historic moment,” he said, referring to a request for the CDC to investigate an urgent public health problem.

To date, the Milwaukee Health Department has identified more than 100 schools built before 1978, when the federal government banned consumer uses of lead-based paints. Around 40 of those have been inspected, Totoraitis said. Six schools have closed since the start of the year due to lead contamination, and only two have reopened.

Around 350 students in Milwaukee have been screened for lead poisoning out of 44,000 identified as having a potential risk, Totoraitis said. The city has confirmed one case linked to lead exposure in school, and two more linked to exposures at both school and home. The health department said it is investigating an additional four cases, which may involve multiple sources of exposure.

Totoraitis said the department is accustomed to looking for lead in homes and rental units, but the CDC was supposed to help them scale that operation to inspect larger buildings. CDC staffers were also supposed to help set up lead screening clinics and investigate where kids had been exposed, he said.

While the health department is handling those efforts on its own now, Totoraitis said it may not have the capacity to screen everyone in a timely manner. He estimated that the department could manage around 1,000 to 1,200 cases of childhood lead poisoning a year. That includes testing kids’ blood lead levels, treating lead poisoning with chelation therapy (which removes heavy metals from the bloodstream) and eliminating exposures in the home by replacing windows and doors.

Totoraitis said he’s hoping to hire two of the terminated CDC employees for at least a couple of weeks to help address lingering questions about how to manage the crisis.

Better yet, he said, “I keep hoping to get an email from them saying, ‘Hey, we got our jobs back.’”