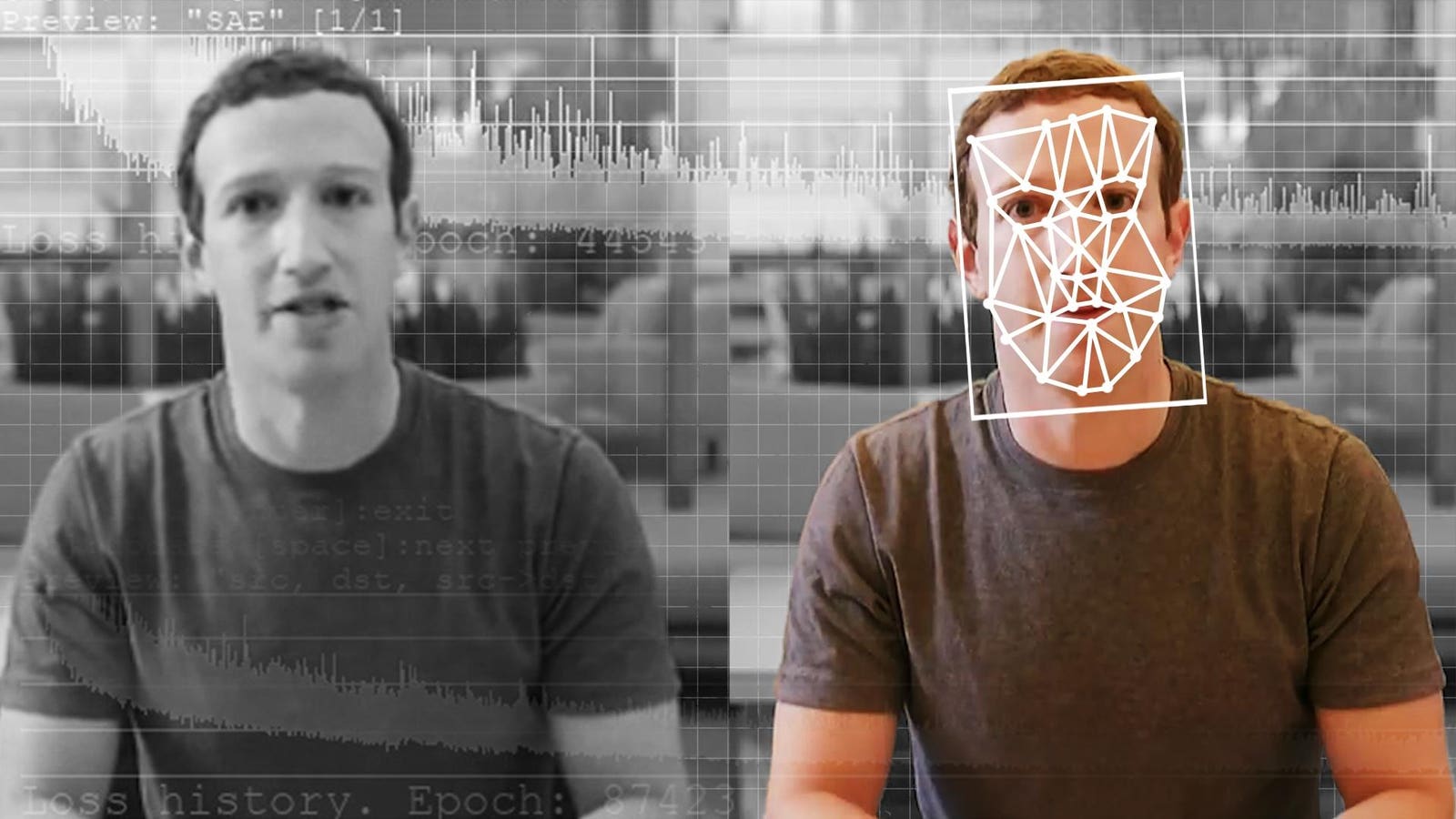

A comparison of an original and deepfake video of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. (Elyse Samuels/The … More

When an explicit AI-generated video of Taylor Swift went viral in January, platforms were slow to take it down, and the law offered no clear answers.

With the lack of an organized regulatory structure in place for victims — famous or not — states are scrambling to fill in the void, some targeting political ads, others cracking down on pornographic content or identity fraud. That has led to a patchwork of laws enforced differently across jurisdictions drawing varying lines between harm and protected speech.

In April, prosecutors in Pennsylvania invoked a newly enacted law to charge a man in possession of 29 AI-generated images of child sexual abuse — one of the first known uses of a state law to prosecute synthetic child abuse imagery.

What began as a fringe concern straight out of dystopian fiction — that software could persuasively mimic faces, voices and identities — is now a predominant issue in legal, political and national security debates. Just this year, over 25 deepfake-related bills have been enacted across the U.S., according to Ballotpedia. As laws finally begin to narrow the gap, the resistance and pushback is also escalating.

Uneven Legal Recourse

Consumer-grade diffusion models — used to create realistic media of people, mimic political figures for misinformation and facilitate identity fraud — are spreading through servers and subreddits with a virality and scale that’s making it difficult for regulators to track, legislate upon and take down.

“We almost have to create our own army,” said Laurie Segall, CEO of Mostly Human Media. “That army includes legislation, laws and accountability at tech companies, and unfortunately, victims speaking up about how this is real abuse.”

“It’s not just something that happens online,” added Segall. “There’s a real impact offline.”

Many recent laws pertain directly to the accessibility of the technology.

Tennessee’s new felony statute criminalizes the creation and dissemination of nonconsensual sexual deepfakes, carrying up to 15 years in prison. In California, where a record eight bills on AI-generated content passed in a single month, legislators have been attempting to regulate a wide range of related issues, from election-related deepfakes to how Hollywood uses deepfake technology.

These measures also reflect the increasing use of AI-generated imagery in crimes, often involving minors, and often on mainstream platforms, but the legal terrain remains a confusing minefield for victims.

Depending on the state, the same deepfake image might be criminal in one jurisdiction but dismissed in another, indicating the growing chaos and discrepencies of state-level governance in the absence of federal standards.

“A young woman whose Instagram profile photo has been used to generate an explicit image would likely have legal recourse in California, but not Texas,” notes researcher Kaylee Williams. “If the resulting image isn’t considered realistic, it may be deemed criminal in Indiana, but not in Idaho or New Hampshire.”

If the person who generated the image claims to have done so out of “affection” rather than malice, the victim could seek justice in Florida, but not Virginia, Williams adds.

Intimate deepfakes are the latest iteration of the dehumanization of women and girls in the digital sphere, states Williams, calling it “a rampant problem that Congress has thus far refused to meaningly address.”

According to a recent study by child exploitation prevention nonprofit Thorn, one in 10 teens say they know someone who had deepfake nude imagery created of them, while one in 17 say they have been a direct victim of this form of abuse.

The harm also remains perniciously consistent: a 2019 study from cybersecurity firm Deeptrace found that a whopping 96% of online deepfake video content was of nonconsensual pornography.

Déjà vu of Section 230, or Federalist Tug-of-War?

Despite the widespread harm, the recent legislative push has met with notable resistance.

In California, a lawsuit filed last fall by right-wing content creator Chris Kohls — known as Mr Reagon on X — drew support from The Babylon Bee, Rumble and Elon Musk’s X. Kohls challenged the state’s enforcement of a deepfake law after posting an AI-generated video parodying a Harris campaign ad, arguing that the First Amendment protects his speech as satire.

The plaintiffs contend that laws targeting political deepfakes, particularly those aimed at curbing election misinformation, risk silencing legitimate satire and expression. A federal judge agreed, at least partially, issuing an injunction that paused enforcement of one of the California laws, warning that it “acts as a hammer instead of a scalpel.”

Theodore Frank, an attorney for Kohls, said in a statement they were “gratified that the district court agreed with our analysis.”

Meanwhile, Musk’s X in April filed a separate suit against Minnesota over a similar measure, contending that the law infringes on constitutional rights and violates federal and state free speech protections.

“This system will inevitably result in the censorship of wide swaths of valuable political speech and commentary,” the lawsuit states.

“Rather than allow covered platforms to make their own decisions about moderation of the content at issue here, it authorizes the government to substitute its judgment for those of the platforms,” it argues.

This tug-of-war remains a contentious topic in Congress. On May 22, the House of Representatives passed the “One Big Beautiful” bill which includes a sweeping 10-year federal moratorium on state-level AI laws.

Legal scholar and Emory University professor Jessica Roberts says Americans are entirely left vulnerable without state involvement. “AI and related technologies are a new frontier, where our existing law can be a poor fit,” said Roberts.

“With the current congressional gridlock, disempowering states will effectively leave AI unregulated for a decade. That gap creates risks — including bias, invasions of privacy and widespread misinformation.”

Meanwhile, earlier this month, President Trump signed the Take It Down Act, which criminalizes the distribution of non-consensual explicit content — including AI-generated images — and mandates rapid takedown protocols by platforms. It passed with broad bipartisan support, but its enforcement mechanisms remain unclear at best.

‘Chasing Tails’

Financial institutions are increasingly sounding the alarm over identity fraud.

In a speech in March, Michael S. Barr of the Federal Reserve warned that “deepfake technology has the potential to supercharge impersonation fraud and synthetic identity scams.”

There’s merit to that: In 2024, UK-based engineering giant Arup was defrauded out of $25 million via a deepfake video call with what appeared to be a legitimate senior executive. And last summer, Ferrari executives reportedly received WhatsApp voice messages mimicking their CEO’s voice, down to the regional dialect.

Against that evolving threat landscape, the global regulatory conversation remains a hot-button issue with no clear consensus.

In India, where deepfakes currently slip through glaring legal lacunae, there is growing demand for targeted legislation. The European Union’s AI Act takes a more unified approach, classifying deepfakes as high-risk and mandating clear labeling. China has gone even further, requiring digital watermarks on synthetic media and directing platforms to swiftly remove harmful content — part of its broader strategy of centralized content control.

However, enforcement across the board continues to be difficult and elusive, especially when the source code is public, servers are offshore, perpetrators operate anonymously and the ecosystem continues to enable rampant harm.

In Iowa, Dubuque County Sheriff Joseph L. Kennedy was reportedly dealing with a local case where high school boys shared AI-generated explicit pictures of their female classmates. The tech was rudimentary, but worked enough to cause serious reputational damage. “Sometimes, it just seems like we’re chasing our tails,” Kennedy told the New York Times.

That sense of disarray may also be relevant to regulators as they look to govern a future whose rules are being constantly written — and rewritten — in code.

In many ways, the deepfake issue appears increasingly Kafkaesque: a bewildering maze of shifting identities, elusive culprits, a tech bureaucracy sprawling beyond regulatory reach — and laws that are always lagging at least a few steps behind.