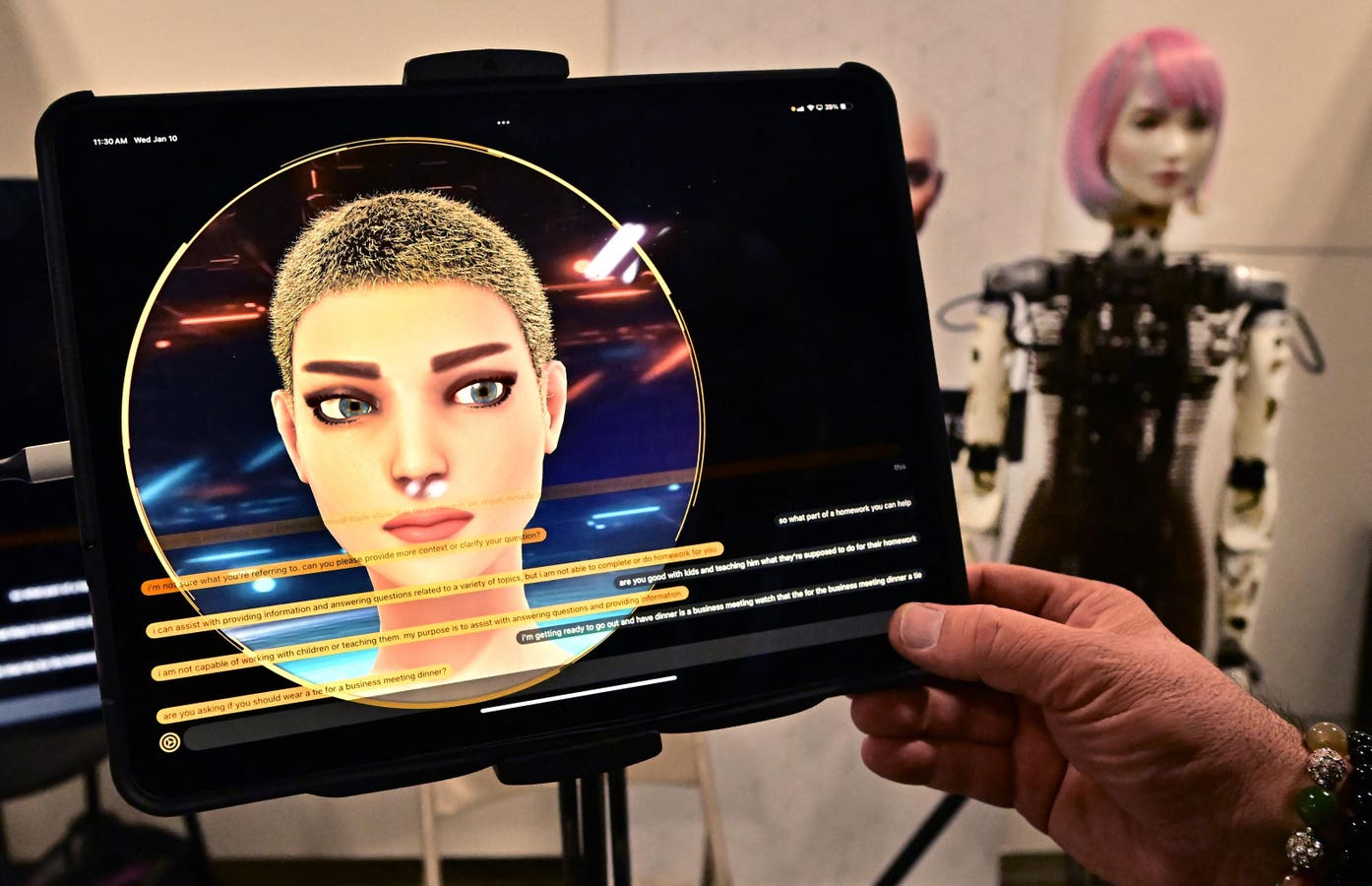

A person has a conversation with a Humanoid Robot from AI Life, on display at the Consumer … More

For users with disabilities, the opportunities for AI to enhance accessibility to digital products and workflows are tantalizing, provided that principles of inclusivity are baked into its design from the outset.

There are significant crossovers with how AI is being deployed today and some of the core precepts associated with digital accessibility. For many consumers, AI is all about productivity and efficiency hacks – making tasks simpler through automation and high levels of personalization. The same ideas can often be applied to accessibility as well.

Speed and efficiency

Nowadays, AI can make significant inroads into tasks such as generating automatic alt text and audio descriptions for the visually impaired as well as real-time captions for those with hearing loss, summarizing and simplifying web content and documents for those with learning or cognitive differences and voice or gesture-controlled home automation systems for those with movement disorders. Very soon, building on research and products available today, AI-powered brain-computer interfaces may help users bypass sensory limitations, while robotic systems could assist with daily tasks and lower the cost of care.

These are just some of the ways that artificial intelligence can supercharge accessibility now and, in the future, but what about the accessibility of the interfaces themselves?

As large language models like OpenAI’s GPT–4o, Google’s Gemini and Anthropic’s Claude rely on conversational interfaces, input/output communication modalities are key to accessibility in this context. For tools utilizing direct voice input, this may include being able to recognize non-typical speech, such as from individuals with a speech impediment. Equally, people with autism and other forms of neurodiversity may both frame the questions they pose to LLMs in different ways and require responses with personalized formatting and levels of detail.

Additional pain points may include the absence of disability inclusive language and concepts in the model’s training data and a lack of codesign and user testing with the disability community before launching new products. Something as simple as poor screen reader accessibility can still dog LLMs, despite their sophistication and advanced capabilities, in just the same way as those with sight loss encountered static web pages more than two decades ago.

Building the internet of the future

Speaking of web pages, what is just as important but often flies below the radar when contrasted with more intriguing futuristic aspects, such as brain-computer interfaces and robotics, is the capacity of AI to complete much of the heavy lifting when it comes to coding the websites and apps of the future. During an earnings call at the end of last year, Google CEO Sundar Pichai revealed that over 25%of Google’s new code was generated by artificial intelligence. Meanwhile, in a recent podcast interview with Dwarkesh Patel, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg suggested that most of the company’s code will be completed by AI in the next 12-18 months further adding that very soon AI agents will be capable of surpassing the tech giant’s elite coders.

In recognition of this impending brave new reality, Joe Devon, the co-founder of Global Accessibility Awareness Day, which is celebrated annually on the third Thursday of May, has devised an innovative new LLM accessibility checker, which was launched in conjunction with this year’s GAAD. The open-source initiative is known as AIMAC, which stands for AI Model Accessibility Checker and involves a collaboration between the Global Accessibility Awareness Day Foundation and user interface and digital workflow specialists ServiceNow.

AIMAC allows testers to evaluate how different models respond to different prompts, such as those related to web page design, layout, and semantic structure, by analysing and benchmarking the accessibility parameters of the returned HTML code relative to what other LLMs are able to produce.

“When you ask an AI to write code for you, it can be accessible or inaccessible,” Devon explains during an interview.

“Moving forward, because the systems are going to be doing so much of the code, I felt that it was really important to be able to compare how accessible different models are. We’ve got the support from ServiceNow to build this out and to open source it, which is so key because, for accessibility, if this is closed source, then you’d have one company using it internally for themselves, to do a better job of the accessible code that they would produce. Instead, by making this open source, it’s going to be possible to democratize the entire landscape of accessibility coding for LLMs.”

ServiceNow has introduced new AI capabilities into its product offerings over the past few months, including more advanced voice features. The company’s VP and Global Head of Accessibility, Eamon McErlean, is a long-term collaborator with Devon, and the pair co-host the Accessibility and Gen AI Podcast.

McErlean firmly believes that though the relative accessibility intricacies of the input/output mechanics of Generative AI models are key, it is within the bigger picture of AI development wherein the greatest threats to accessibility and equality lie.

“Accessibility was an afterthought for many years within the .com world,” says McErlean.

“Thankfully, a lot of companies have since jumped on to resolve and to catch up. But the speed that Gen AI is going right now, accessibility can’t be an afterthought because playing catch-up in that arena is going to be exponentially more difficult, and that could end up being dangerous.”

Back in the latter stages of the .com era, what helped move accessibility away from being viewed as an onerous burden was its dual establishment as both a legally protected human right as well as being a competitive advantage for those willing to invest in it. Hopefully, regardless of the breakneck pace of current AI developments, those same principles will hold once more. For our AI-driven future to be truly inclusive, accessibility must not only serve as a design principle but also be a foundational requirement — embedded into the very code powering the digital world.