LONDON — For the first time in modern history, far-right and populist parties are simultaneously topping the polls in Europe’s three main economies of Germany, France and Britain.

A poll Tuesday showed Alternative for Germany — which is under surveillance by the country’s intelligence services over suspected extremism — is now the most favored by voters. The survey by broadcaster RTL put the AfD at 26%, ahead of the ruling Christian Democrats at 24%.

This is a high watermark for the European far right, a once fringe movement whose virulently anti-immigration, anti-Islam and culture-war politics were shunned by the mainstream just a decade ago. Today, these parties have developed deep ties with President Donald Trump and his Republican allies, who openly cite nationalists such as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán as inspirations on policy and tactics.

For years, France’s National Rally has consistently led polls ahead of the country’s next presidential election in 2027. And Britain’s Reform U.K., led by Trump ally and friend Nigel Farage, has since April topped most polls there.

Far-right parties have been elected over the past few years into the governments of Italy, Hungary and elsewhere. The center right and the center left have hemorrhaged votes amid high inflation, fears over immigration and collapsing faith in institutions — all familiar issues in America, too.

Tuesday’s polling milestone is “a sign of the power of populism, disinformation and the failure of established parties to understand what is happening,” said Nic Cheeseman, a professor of democracy and international development at England’s University of Birmingham.

Though the far right has been making gains for the past decade, Cheeseman believes the polls showing the far right leading Europe’s top three economies is “a first — at least in modern times.”

There is no guarantee that London, Berlin and Paris will be ruled by far-right parties; these countries’ next elections are not until 2029, 2029 and 2027 respectively. These groups are all polling in the 20s and 30s percentage-wise, enough to lead polls in Europe’s multiparty systems but not enough to govern alone outside of a coalition.

Most of Europe’s politicians on this former fringe reject the “far right” label, with its historical connotations of the Nazism that marauded the continent 80 years ago. Many scholars say these parties nevertheless fit the academic model, defined by nativism — the idea that perceived “non-native” groups threaten their social fabric — and harsh punishments for criminality.

The roots of the far-right surge lie in the world financial crisis of 2008, which prompted government to cut budgets for public services and lowered living standards, some experts say, compounded by the Arab Spring of 2011 that birthed civil war in Syria and a mass refugee crisis in Europe four years later.

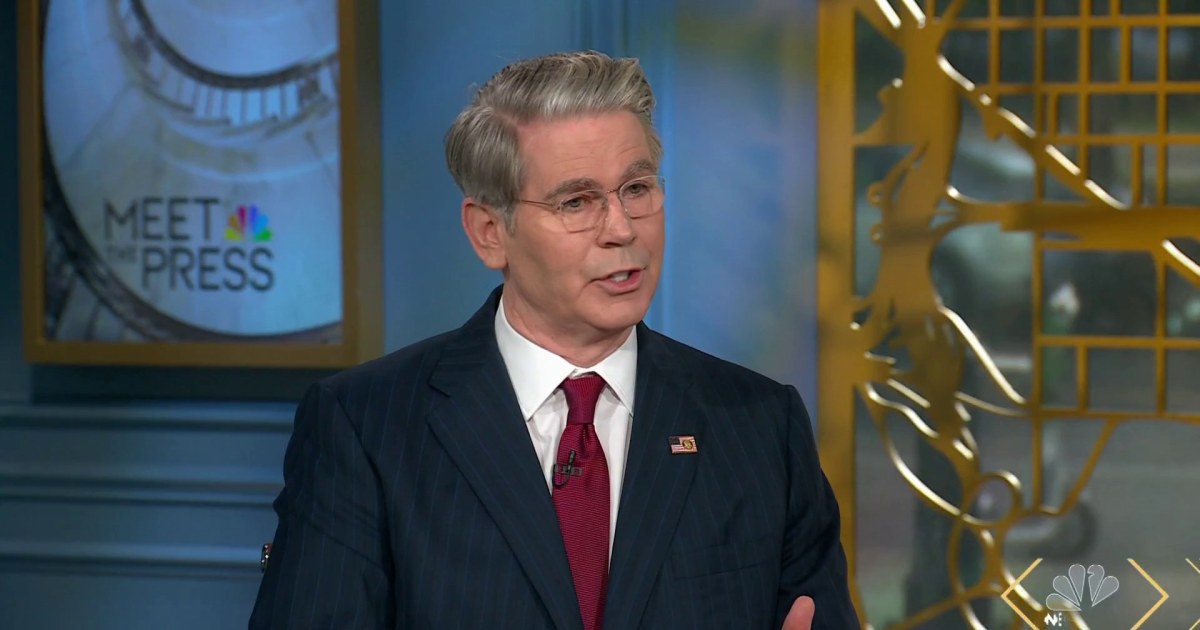

More recent societal stressors such as the coronavirus pandemic and war in Ukraine have further increased the allure of populism, according to Hans-Jakob Schindler, the senior director of the Counter Extremism Project, a nonprofit international group. But populist parties in Europe have also harnessed social media more powerfully than their more centrist opponents, he said.

“They are masters of using social media much better than any of the more established parties,” he said. “When you have easy solutions to complex problems” — as he says populist parties do — “it’s easier to communicate than complex political issues that the actual parties, who do politics rather than just doing populism, will have to deal with.”