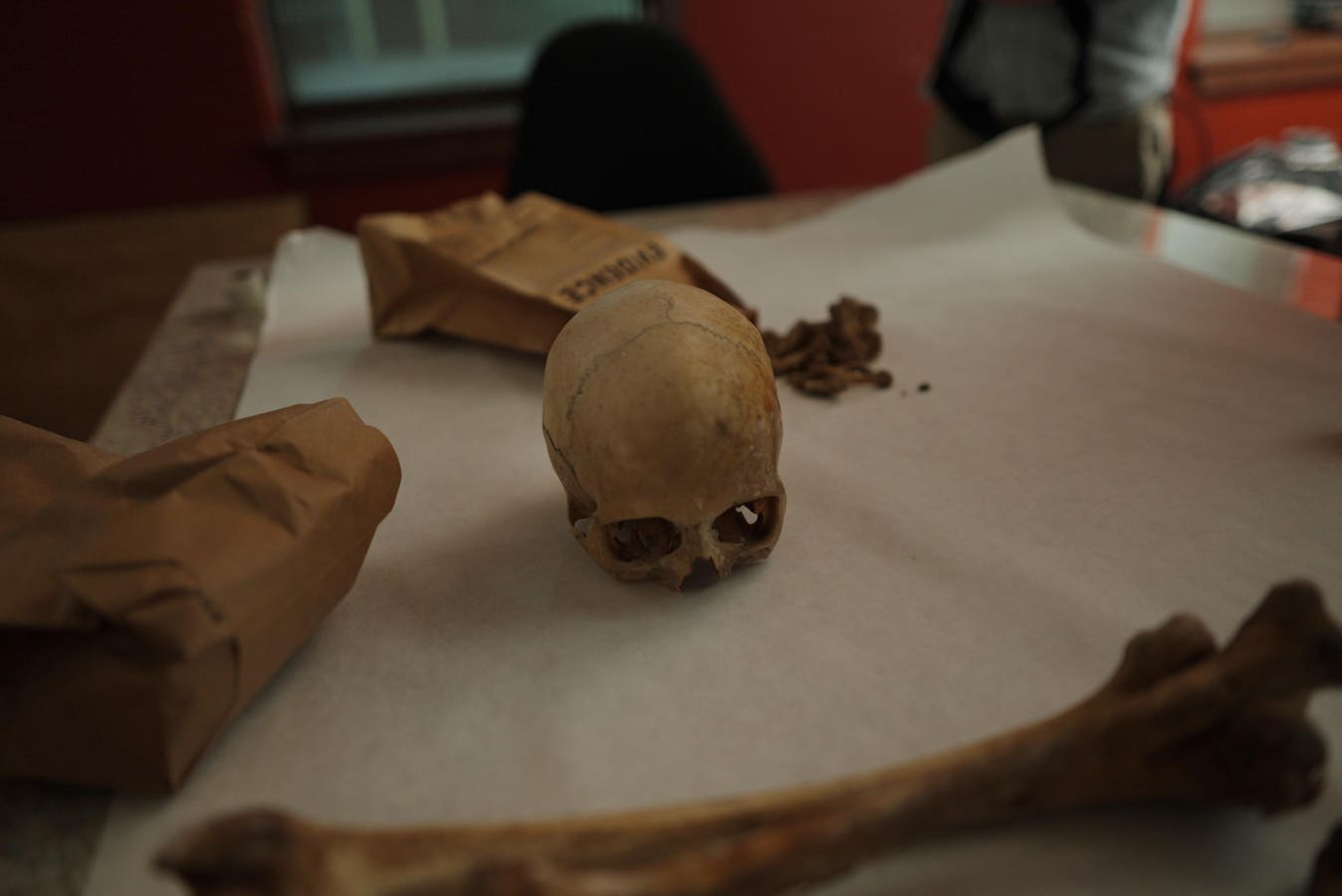

Jane Doe’s skull and bones on the examination table at the Smith County Sheriff’s Office. (National Geographic/Will Francome)

National Geographic/Will Francome

Across the United States, more than 50,000 people have died without a name. These are individuals who were never identified, never claimed and often never mourned. But thanks to forensic technology and the growing use of genetic genealogy, that’s beginning to change.

Naming the Dead, a six-part docuseries from National Geographic, brings this invisible crisis to light. The series follows the DNA Doe Project, a nonprofit using cutting-edge DNA analysis and open-source genealogy tools to solve some of the country’s most confounding cold cases.

It’s a quiet revolution in forensics, powered by algorithms, datasets and persistence.

From Data to Identity

The process of forensic genetic genealogy begins by extracting DNA from unidentified remains. That data is then uploaded to public databases in search of distant relatives. It might sound simple, but it rarely is.

Samples are often degraded, especially if they’ve been buried or exposed to the elements for years. Sequencing has to be precise. And even when a viable DNA profile is produced, the real challenge starts: building family trees from matches that might be third or fourth cousins, or even more distant.

I recently spoke with Jennifer Randolph, director of the DNA Doe Project, about the objective of her and her team, and about this Nat Geo series. She described the work as “a really large logic puzzle.” She added, “Our genetic genealogy volunteers really like that kind of a challenge… you get pretty excited because it’s that feeling of, you know, you’re on the cusp of resolving this puzzle.”

That excitement is balanced by the gravity of the work. “It becomes very bittersweet,” she said. “We know that some family is going to get a knock on the door and they’re going to get not the news they hoped for.”

It’s resolution, not closure—but it’s more than many of these families have had in decades.

My Experience with Genetic Discovery

A few years ago, I submitted a DNA test through Ancestry.com. It was mostly out of curiosity, but also with the hope of finding a missing uncle—my mother’s brother—who was separated from the family while they were in foster care. We only have one photo of him as a toddler, and for most of my life, I’ve wondered where he ended up.

I didn’t find him. But I did find someone else.

The results revealed that I had a half-brother I never knew existed. We’ve since connected. We’ve met. We’ve had the conversations you never expect to have in your 40s or 50s. The circumstances are complex, but that’s the nature of family sometimes. What’s important is that the technology gave us a way to discover one another.

That experience helped me understand just how powerful this work can be—especially for families of the unidentified dead. It’s not just about science. It’s about being seen. It’s about making the anonymous known.

The Tech Making It Possible

The show emphasizes how far the technology has come. Advances in next-generation sequencing have made it possible to work with even the most degraded samples—sometimes from cases that are 30 or 40 years old. That data is then uploaded to public databases like GEDmatch, FamilyTreeDNA and DNA Justice.

While private services like AncestryDNA and 23andMe hold the largest databases, they don’t allow uploads of profiles from unidentified remains. That limitation means the work of the DNA Doe Project depends on much smaller pools of data—typically between 1.5 and 2 million profiles.

That makes each match even more critical. Randolph noted the impact of visibility and public education, saying, “We’ve had more than one instance where someone learned about [this technique], had a missing person in their family and decided to upload to GEDmatch. And then—out of the blue—a high match, like a niece, appears. And once you have that, you know you’re there.”

In other words, awareness is its own kind of technology multiplier.

Infrastructure for Justice

Behind the breakthroughs is a growing ecosystem of cloud-based collaboration. Investigators, coroners, volunteers and data analysts work across states and time zones using shared digital tools. Case notes, DNA files and potential family trees are securely stored and accessed in real time.

What used to be the work of entire agencies can now be supported by distributed teams using pro bono platforms. The DNA Doe Project itself operates as a nonprofit, often covering both the cost of lab work and the countless hours of volunteer research it takes to identify a single person.

That’s one of the reasons this show matters. Visibility attracts donations, but it also sparks interest from law enforcement. As Randolph explained, “We want every Jane and John Doe to have the opportunity to be identified, no matter who they are or how tough the case might be. So we do try to get the word out at conferences… and then they learn about us through word of mouth.”

Beyond the Lab

Naming the Dead doesn’t glamorize the work. There are dead ends. Cases stall. Some episodes end with possibilities, not certainty. But the emotional core is steady—this is about restoring dignity, not just solving puzzles.

And the tech, as powerful as it is, still relies on human effort and intention. None of this happens without people willing to volunteer time, apply pressure and keep showing up for the forgotten.

It’s worth remembering that some families have waited 20 or 30 years for answers. That kind of silence can be corrosive. When resolution comes—whether through a second cousin match or a last-minute database upload—it opens the door to grief, remembrance and sometimes, healing.

Naming the Dead premieres August 2 on National Geographic and streams the next day on Disney+ and Hulu. New episodes run through September 6.