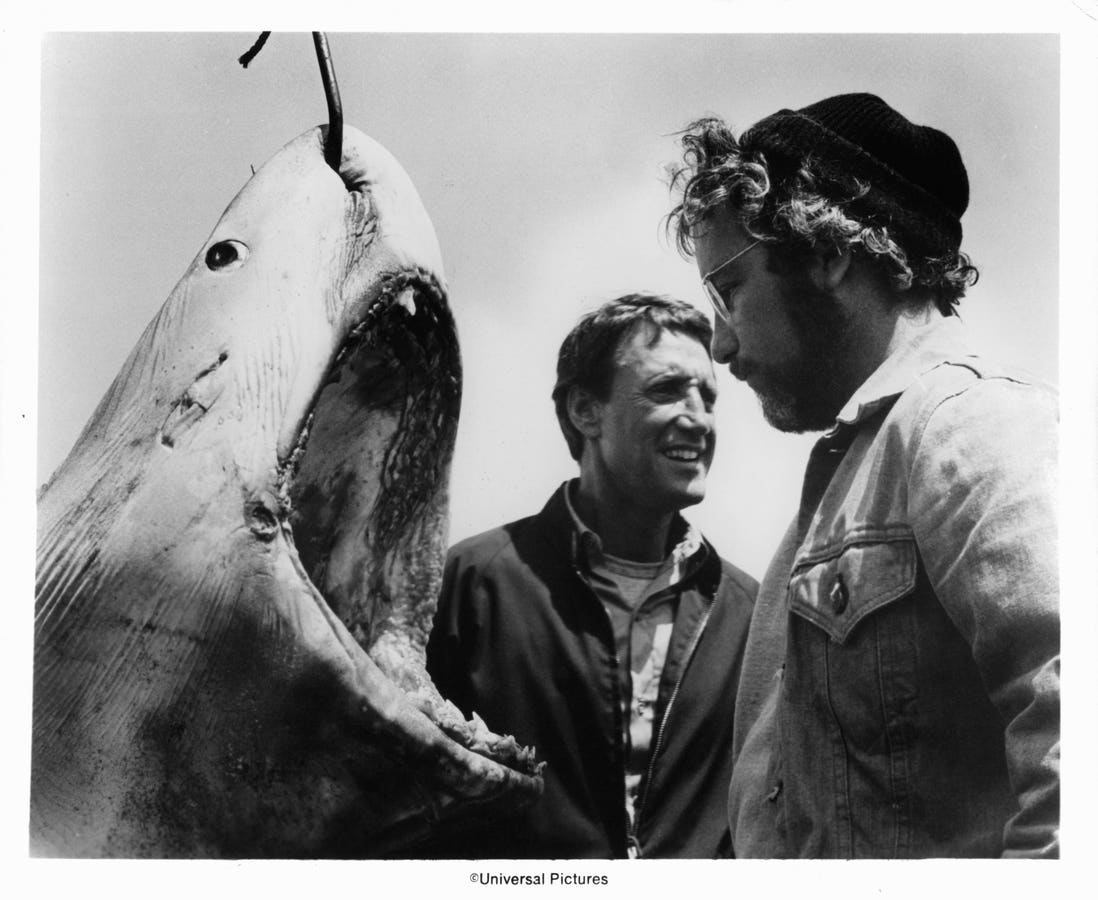

Roy Scheider and Richard Dreyfuss stand next to a shark with a hook piercing through it in a scene … More

When Jaws hit theaters in 1975, it changed the way people saw sharks literally overnight. Before the film, most beachgoers didn’t think twice about what swam below the waves. But after that ominous music and the now-iconic dorsal fin? Well, sharks became public enemy number one. The problem with this was that the fear people felt didn’t stay in the cinema. It bled into science, policy, and the public’s understanding of the ocean… and half a century later, sharks are still paying the price.

Since 1970, shark populations in the open ocean have dropped by more than 70 percent. While overfishing plays the major role for the downfall of this iconic predator, the fear-driven policy following the cultural hysteria of Jaws can’t be ignored. Around the world, governments implemented shark culls, protective nets, and baited drumlines — all in the name of “public safety.” But many of these tools aren’t just ineffective but counterproductive! They killed not just the so-called “dangerous” sharks but also countless other marine animals like rays, turtles, and dolphins. As shark numbers dropped, ecosystems began to shift. See, sharks aren’t just big, toothy fish that swim around scaring humans out of the water. They’re apex predators that help keep marine systems balanced; take them out of the picture, and you risk destabilizing entire food webs. In coral reef systems, for instance, sharks help regulate populations of mid-level predators, which in turn keeps algae-eating fish populations healthy. Remove the sharks, and the algae overgrow. Coral suffers, and the reef — home to thousands of species! — starts to die. That’s not just an environmental tragedy. It’s an economic one too.

Scientists estimate that ecosystem disruptions caused by shark declines could cost coastal economies billions of dollars. Coral reefs alone support an estimated $36 billion in tourism each year, and healthy shark populations are a major draw. In places like the Bahamas, Fiji, and Palau, shark tourism brings in tens of millions of dollars annually. But some of these same nations have also had to spend significant amounts managing shark-human conflict, often trying to strike a balance between public safety and tourism dollars. In Australia, for example, the government has spent millions maintaining shark net and drumline programs along popular beaches. Yet studies show these measures don’t significantly reduce the risk of shark bites. Meanwhile, they continue to kill innocent (and sometimes endangered) species and strain budgets that could be better spent on education campaigns, improved tracking systems, and research into shark behavior — tools that can actually reduce risk without harming the environment, and that the public has supported.

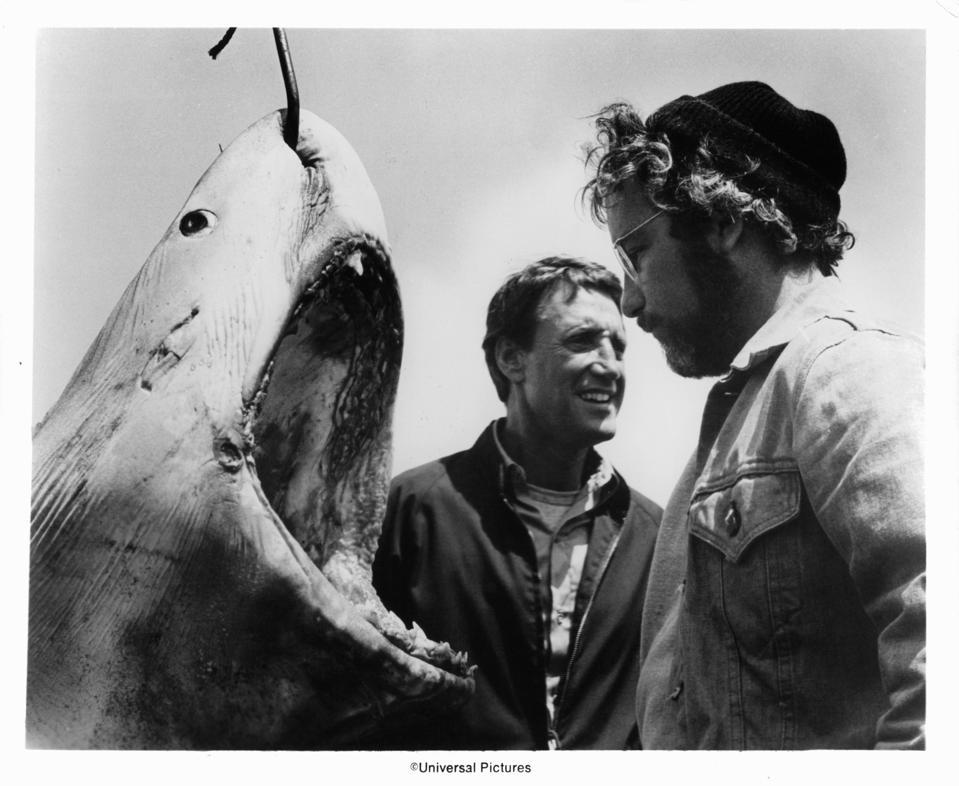

American actor Richard Dreyfuss inspects the mouth of a dead shark in a still from director Steven … More

The media’s portrayal of sharks hasn’t helped either. Even today, headlines about shark bites often use the language of “attacks,” reinforcing the myth of sharks as mindless killers. In reality, the odds of a fatal shark bite are one in 3.75 million. To put this into perspective, you’re more likely to die taking a selfie or being struck by lightning. But logic rarely wins against fear, and for years, fear has dictated how we treat sharks in science, policy, and the public mind.

Ironically, the same fear that fueled shark culling has also inspired a global fascination with sharks. From Shark Week documentaries to Instagram influencers diving cageless, there’s growing public interest in these animals and that gives us an opportunity to rewrite their story. But shifting perception isn’t enough to help these animals overcome the threats they are currently facing. It’s going to take stronger policies, international cooperation, and meaningful investment in shark conservation to undo the decades of damage this movie helped create. Thankfully, in recent years, nations have started to recognize the value of live sharks over dead ones, and more countries are banning shark finning or setting science-based catch limits. Marine protected areas are expanding, and several species of sharks are being protected by governments on all types of levels. But the clock is ticking. Some shark species now hover on the brink of extinction, and without urgent action, they could disappear within our lifetimes.

Fifty years after Jaws, we have the benefit of hindsight and the burden of accountability. The movie made people afraid — now it’s time for science and policy to make them understand that sharks aren’t villains. They’re vital. And if we don’t protect them, we’re the ones who’ll end up with the real horror story.