Far too many animals from Earth’s second-most remote continent have gone extinct in the past 10,000 years. Here’s one such example.

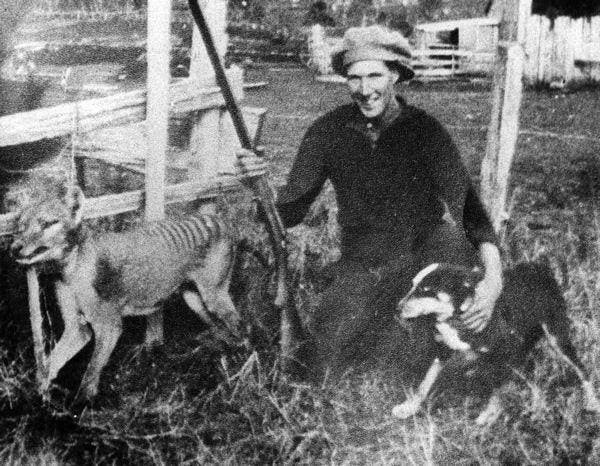

By Unknown author – http://tasphotos.blogspot.com/2009/02/wilfred-batty-and-his-tasmanian-tiger.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11957745

In the year 1930, a striking photograph was taken. To this day, it remains one of the most poignant reminders of extinction. In it, is Wilf Batty, a Tasmanian farmer, standing beside the lifeless body of a thylacine; the last known of its species, killed in the wild.

While this image is often overlooked in broader discussions of extinction, it marks the end of a predator lineage that had survived for millions of years before.

To the untrained eye, the animal resembles a dog or a wolf, but key differences emerge on closer inspection. Its posture is stiffer, its tail more like that of a kangaroo and its lower back is striped, almost like a tiger’s. This was Thylacinus cynocephalus — the thylacine — a carnivorous marsupial and the last representative of a once-diverse family of predators found only in Australia and New Guinea.

As an evolutionary biologist who has studied mammalian fauna, I can attest that the extinction of the thylacine was so much more than a loss of a species. In fact, it may have silenced an entire evolutionary narrative.

A Predator Living In Isolation

The thylacine, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, as featured on a 1960’s era Australian stamp.

getty

The thylacine belonged to a group known as the Dasyuromorphia, a marsupial order that includes modern relatives like quolls and the Tasmanian devil. Marsupial carnivores evolved in relative isolation on the Australian continent, occupying ecological niches that, elsewhere in the world, were filled by placental mammals like wolves, foxes and big cats.

The thylacine was a classic case of convergent evolution, which is the process by which unrelated species evolve similar traits to adapt to similar environments. Though genetically closer to kangaroos than to dogs, the thylacine evolved a dog-like skull and body shape, reflecting its role as a top predator in an ecosystem without canids.

By the time of European colonization, the thylacine had long disappeared from mainland Australia, likely pushed out by a combination of changing climates, human hunting and the introduction of the dingo around 3,500 years ago. Tasmania, isolated by the Bass Strait, became its final refuge, until colonial pressures reached its shores as well.

The Collapse Of The Thylacine

From the early 1800s, European settlers began to view the thylacine as a threat to their newly introduced livestock. Though evidence for large-scale sheep predation by thylacines remains weak, they were nonetheless labeled a nuisance species. By 1888, the Tasmanian government instituted a bounty system: one pound for each adult thylacine and ten shillings for every pup.

What followed was a strict campaign of eradication. Thousands were killed over the following decades, and their populations declined rapidly. Beyond direct persecution, several ecological pressures likely hastened their decline, including:

- Habitat loss due to land clearing and agriculture

- Competition with introduced species, especially dogs and later foxes

- Potential disease, which may have swept through remaining populations in the early 20th century

Despite sporadic sightings, the last confirmed wild thylacine was shot in 1930. This is the one lying by Wilf Batty’s side in that final, haunting photograph. The final captive thylacine, often referred to as Benjamin, died in Hobart Zoo in 1936. In 1938, the species was officially declared extinct.

Oceania: The Global Extinction Hotspot

The thylacine’s extinction is emblematic of a broader crisis in Oceania. This region, which includes Australia and its surrounding islands, has experienced the highest rate of mammal extinctions in the modern world. Since European colonization, more than 30 mammal species have vanished in Australia alone.

But why is it this region that’s become a hotspot for extinction? The answer lies in its evolutionary isolation. Australia’s mammals evolved without the pressures of placental predators. When Europeans introduced cats, foxes and other invasive species, native wildlife had no evolutionary defenses.

Moreover, the continent’s arid climate and fire-adapted ecosystems are uniquely vulnerable to disturbance. As climate change accelerates and land use intensifies, more species face the same pressures that doomed the thylacine.

The Allure (And Limits) Of De-Extinction

In recent years, the thylacine has become a poster child for de-extinction — the scientific effort to “resurrect” extinct species through genetic engineering. With its genome now sequenced, some researchers are exploring the possibility of using modern marsupials as surrogates to bring the thylacine back.

While this is an exciting avenue of research, it’s important to remain clear-eyed about its limitations. Recreating an organism is only part of the challenge. Restoring its ecological role, ensuring its survival in altered environments and preventing the same factors from re-erasing it are far greater hurdles that must be accounted for.

From a conservation biology standpoint, the energy and funding required for de-extinction might be more effectively spent protecting critically endangered species that still have a chance today.

What The Thylacine Teaches Us

The loss of the thylacine is not just a tragedy of a species gone extinct. It’s a case study in how complex ecological systems can unravel quickly under human pressure. It’s also a warning that even widespread species can become vulnerable when perception, policy and economics override science.

Today, conservation biologists are still reckoning with the consequences of that loss. This has impacted Tasmania, predator-prey dynamics, ecosystem resilience and how we think about our responsibilities as stewards of biodiversity.

If there’s any lesson to be drawn from the last photos of the thylacine, it’s this: extinction is not inevitable. It’s a process — often human-driven — that can be interrupted, reversed or prevented, but only if we act before the last image is taken; not after.

Does thinking about the extinction of a species instantly change your mood? Take the science-backed Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension.