Sometimes, drastic measures must be taken to restore ecological balance in an affected area. Here’s … More

Island ecosystems are some of the most delicate that can be found on planet Earth. The loss of an apex predator, the introduction of an invasive species or even minor changes in climate or weather events can send island ecosystems into a tailspin.

Fixing these problems can be incredibly challenging – but not impossible. For proof of this, we can look to Mexico’s Socorro Island and how scientists teamed up with government officials and the military to undue much of the damage caused by human activity on the island.

Fixing The Ecosystem Of Socorro Island

Socorro Island is a remote pacific island approximately 375 miles off the coast of Mexico’s western shore. Discovered by Spanish explorers in 1533, it remained largely uninhabited for centuries until the Mexican Navy established a base there in 1957. The island is volcanic in origin, with rugged terrain and a dry subtropical climate that supports unique flora and fauna found nowhere else on Earth.

Socorro is part of Mexico’s Revillagigedo National Park and spans approximately 50 square miles. It is the Mexican island with the highest level of endemism: the island provides habitat for 117 vascular plant species, of which 26% are endemic. It is also home to eight endemic terrestrial bird species and the Socorro blue lizard.

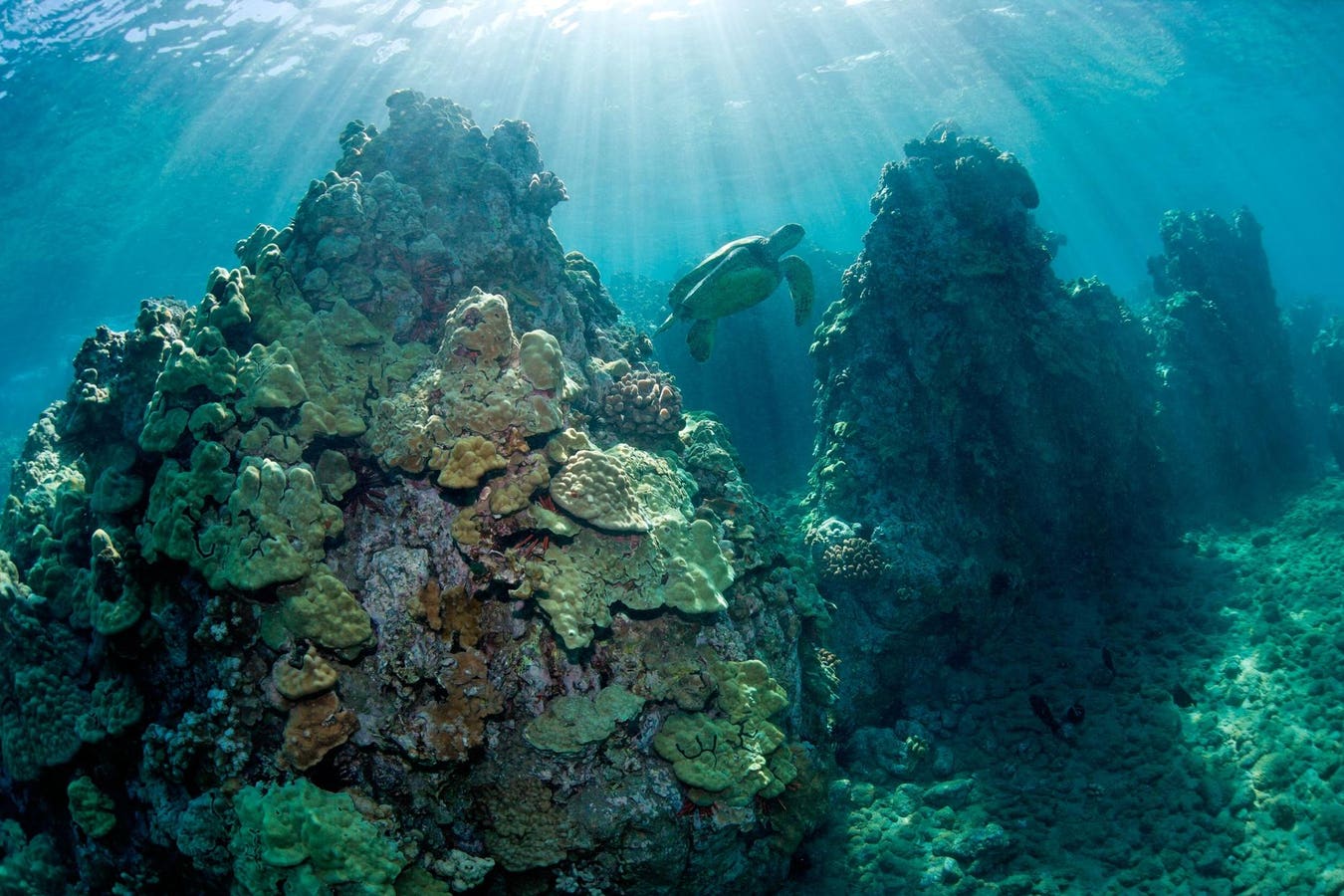

The rugged coastline of Socorro Island, a remote Pacific outpost home to some of Mexico’s rarest … More

However, this remarkable biodiversity was nearly destroyed following the introduction of invasive mammals brought by humans – specifically, feral sheep and domestic cats.

The sheep, introduced over a century ago, grazed uncontrolled and destroyed nearly a third of the island’s vegetation, leading to severe soil erosion and habitat degradation. Meanwhile, feral cats decimated native bird populations and preyed heavily on the Socorro blue lizard. The Socorro dove and the Socorro elf owl became extinct in the wild due to predation and habitat loss, while other species like Townsend’s shearwater were pushed to the brink.

Recognizing the crisis, a large-scale eradication effort of sheep and cats began in 2009. Using helicopters, trained snipers, and advanced tracking methods like radio-telemetry-collared “Judas sheep” (i.e., sheep that served only to help locate remaining herds), 1,762 feral sheep were eliminated by 2012.

Helicopter sniping was the most successful form of eradication. In the span of two days (or 35 flight hours), snipers removed 1,257 sheep.

Feral sheep destroyed one third of Socorro Island’s habitat, grazing native plants to the brink and … More

A cat eradication campaign followed, starting in 2011, involving leg-hold and lethal traps with telemetry systems. By 2016, over 500 cats had been removed, with populations continuing to decline toward complete eradication.

With the invasive populations all but wiped out, vegetation recovery was rapid and dramatic, with notable improvements in soil quality and plant diversity.

The results have been extraordinary. Native bird and lizard populations are rebounding, vegetation cover is expanding, and the ecosystem is stabilizing. With feral cats nearly eradicated, the island is entering a new phase of recovery, proving that even severely degraded island ecosystems can be improved with the right combination of science, persistence and resources.

A Global Challenge: Other Islands Fighting Invasive Species

Socorro Island’s success is not an isolated case. It reflects a broader global movement to protect island ecosystems from invasive species, which are among the leading causes of extinction worldwide. Many islands, once considered biodiversity hotspots, have suffered devastating losses due to introduced predators, herbivores and plants.

Conservation efforts sparked a remarkable recovery on Socorro Island, but not in time for all … More

Take New Zealand, for example, where the Department of Conservation has spent decades removing invasive stoats, rats and possums from offshore islands. Thanks to these efforts, species like the kakapo and tuatara have been reintroduced to predator-free sanctuaries.

Similarly, on the Galápagos Islands, intensive control of invasive goats, pigs and donkeys has led to the recovery of native vegetation and the comeback of iconic species such as Galápagos tortoises.

(Sidebar: Socorro isn’t the only island transformed by invasive species. Learn how a house cat named Tibbles triggered a bird extinction on Stephens Island, and how a wasp helped rescue a struggling species on Christmas Island.)

In the sub-Antarctic, South Georgia Island underwent one of the largest rat eradication programs in history. With helicopters dispersing bait across treacherous terrain, the project successfully removed invasive rodents that had devastated seabird colonies for over two centuries. Today, bird populations are returning to breed in healthy numbers.

Despite these successes, eradication programs are not without controversy or challenge. They require massive logistical efforts, are often costly, and can provoke ethical debates over the use of lethal methods. Nonetheless, the ecological benefits of removing invasive species, especially on island ecosystems, are well-documented.

Does thinking about the disruption of island ecosystems instantly change your mood? Take the Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension.