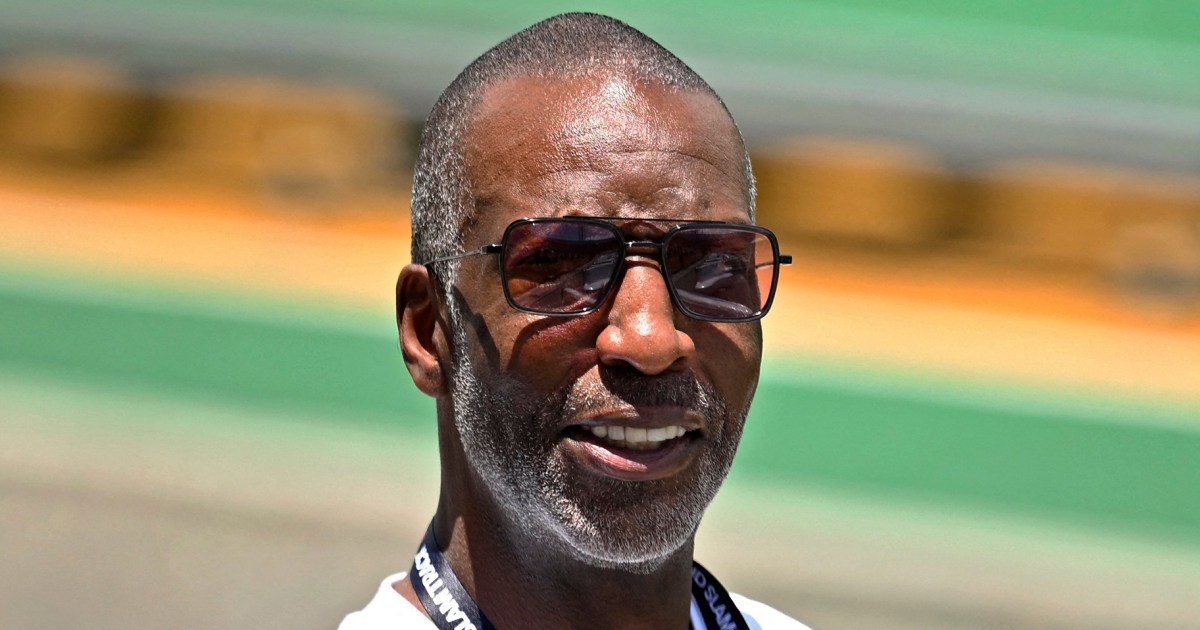

As summer began in 2024, former Olympic gold-medal sprinter Michael Johnson stood in a downtown Los Angeles restaurant that had been rented out for a big announcement. Johnson said he had secured $30 million in funding for a new track league, promising payments never before seen in track and field.

In a sport where even top stars earn modest livings by the standards of professional athletes, Grand Slam Track represented a huge windfall. More than one-third of that promised funding would be earmarked for prize money alone, a pool of more than $3 million per meet. And the biggest winners at each of its four meets would pocket $100,000 per meet — five times as much as first place earned on track’s other global circuit.

Additionally, 48 competitors who signed contracts with the circuit could earn an annual base compensation, plus a cut of revenue from group licensing.

Yet just 14 months after Johnson’s grand announcement, and four months after the group held its first meet in Jamaica, Grand Slam Track has yet to pay many of its athletes and vendors, and Johnson acknowledged Friday that the cash crunch — what one source said was around $13 million in unpaid money to athletes alone — poses an existential threat to the fate of the circuit returning for a second season.

“The cruelest paradox in all of this is we promised that athletes would be fairly and quickly compensated. Yet, here we are struggling with our ability to compensate them,” said a statement signed by Johnson that was posted on social media Friday.

Johnson also maintained that he is “confident about the future of Grand Slam Track.”

NBC News spoke with four agents who represent multiple athletes still owed money by Grand Slam Track, who spoke on condition of anonymity to retain relationships with organizers. Three expressed serious doubts the circuit would be able to drum up enough funding from investors and confidence from athletes to return for a second season, in 2026. A fourth said he was willing to give the benefit of the doubt, for now.

“My message to our athletes is, look, it’s not good,” that agent said. “But on the other hand, their intent is to pay and we’re going to wait for them to pay us. Otherwise, they won’t have a future.”

Agents, coaches and meet organizers in track and field said their concerns about Grand Slam’s trouble go far beyond receiving the money owed from the three meets it hosted this spring in Jamaica, Florida and Philadelphia. If Grand Slam Track were ultimately successful in drawing strong ratings and crowds, there was a hope that such demand could entice more outside investors with deep pockets to pour money into a sport that often operates on shoestring budgets compared to other professional leagues.

“It feels like to a lot of people that this will be a massive deterrent to future endeavors,” said Paul Doyle, a prominent athlete agent who founded and has also operated a pro track circuit, the American Track League, since 2014. “It wasn’t all negative. I feel for them in that sense that they’re in a tough spot.”

On the day Johnson announced Grand Slam Track in 2024, he was bullish but also admitted the venture would take time to generate money.

“If I had an investor who said, ‘Well, I need it to be profitable in Year 2,’ I would not take their money because that’s impossible,” Johnson said in 2024. “It’s just not going to happen. Our investors have come on and said, ‘Hey, we believe in the long-term viability of this.’”

That viability has been under scrutiny ever since Grand Slam Track canceled its fourth and final meet, scheduled for June. It emailed athlete representatives in July notifying them that earnings from their first meet, held in Jamaica in April, would be paid by that month’s end. On Aug. 4, a spokesperson for Grand Slam Track said that it was “anticipating investor funds to hit our account imminently, and the athletes are our top priority.”

As of Friday’s announcement, however, Grand Slam had only paid athletes for the appearance fees they were owed in Jamaica, but not any prize money.

Johnson, in his statement, suggested that the funding shortfall was due to a change in circumstances “in ways beyond our control.” Johnson previously told Front Office Sports that an investor had pulled funds.

“Due to our strong desire to make this right as quickly as possible, we offered dated payment timelines and have been unable to meet them,” Johnson said in Friday’s statement. “Understandably, this has led to frustration, disappointment, and inconvenience to our athletes, agents, and vendors. I know this damages trust. I know this makes some wonder if our vision can survive. That is why we are not just addressing the immediate problem; we are putting systems and partnerships in place to make sure it never happens again.”

“While I am no stranger to setbacks and overcoming obstacles, as an athlete, professionally, and personally, this current situation of not being able to pay our athletes and partners has been one of the most difficult challenges I’ve ever experienced,” the statement added.

Prize money payments that take weeks to arrive are not unusual in track and field; if anything, they are the rule. In extreme cases, athletes have said that prize money payments have taken more than a calendar year to hit their accounts. Prize money from March’s world indoor championships in China still has yet to arrive, one agent said. Delays largely stem from drug testing, because meets typically wait to pay until knowing an athlete was clean. Results generally take 10-30 days to return. In contracts with its “racers,” Grand Slam Track stated that drug testing would be completed within 21 days of each meet, and that an athlete’s promotional fee and earned prize money would be paid within 10 days of learning the doping results, according to a source.

Delays are commonplace. But what made Grand Slam Track different, one agent said, was that there was a belief it already had its announced $30 million in funding waiting in escrow, ready to pay as obligated.

Instead, they now wait for emailed updates from Grand Slam organizers.

“You’re not getting anything directly answered,” one agent said. “‘Our goal is to pay.’ Well you can pay, but when? That doesn’t sit well with anyone.”