For as long as she can remember, Heather Thiel believed her father was a killer.

She was so convinced that she twice urged authorities to examine whether he was responsible for a horrific, unsolved double murder that shook rural Wisconsin more than three decades ago.

But her role in the investigation into the slaying of Tim Mumbrue and Tanna Togstad led to an outcome she never could have imagined: three years ago, authorities concluded that her cousin, not her now-deceased father, fatally stabbed the couple on March 21, 1992.

Just as head-spinning, that cousin, Tony Haase, was acquitted in the murders earlier this year. During a nearly monthlong trial, Haase’s lawyers made the case that the evidence pointed at Heather Thiel’s dead father, Jeff Thiel.

For Heather Thiel, who is 40 and works at a group home for mentally ill adults, the whiplash of the last three years left her questioning longstanding beliefs and wrestling with a familiar feeling.

“I wish there was a definite answer,” she said. “Now, I feel like we still don’t know for sure.”

Fixated on murder

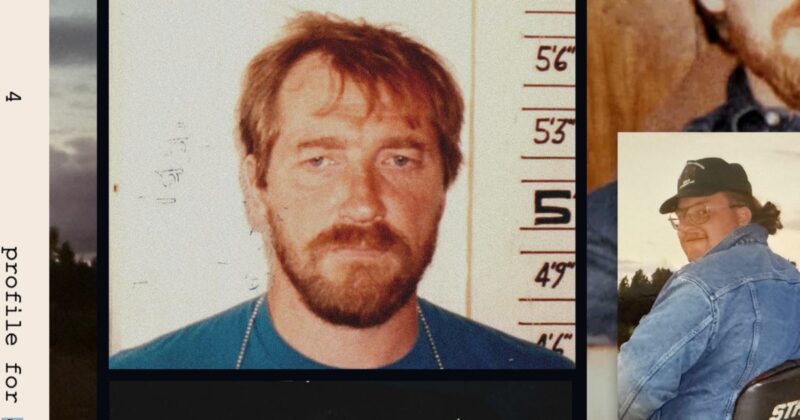

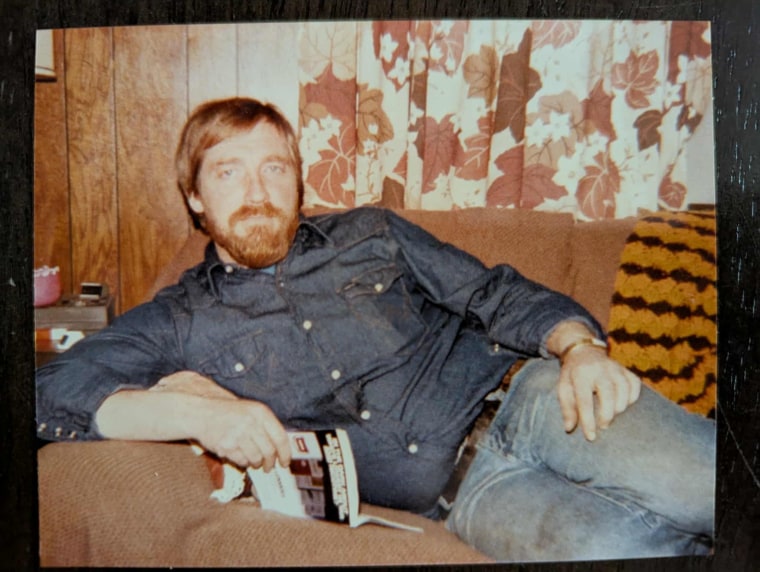

On March 11, 1995, Jeff Thiel pointed a shotgun at a law enforcement officer after he was pulled over in a traffic stop. The officer retreated to his car, and Jeff Thiel, who’d worked in the maintenance department of an iron foundry in a rural community east of Green Bay, escaped, Haase’s defense attorney said at trial.

He blew through a roadblock and fled the state, said the attorney, John Birdsall.

Nearly three months later, in a hotel room in Washington state, Jeff Thiel died by suicide, according to his daughter. He was 44.

Heather Thiel, who was 11 when her mother told her the news, can still recall her response:

“I said, ‘When’s the party?’”

Heather Thiel described her father as a scary and abusive parent who killed neighborhood pets and would casually — and routinely — threaten to shoot her mother. Her mom, Marie Stanchik, also believed her ex-husband was a killer. In an interview with authorities three years ago, she recalled how his “ultimate dream was to kill somebody.”

“He used to tell me that all the time,” Stanchik said, according to audio of the interview. “He’s had a gun in my face and said if I ever call the cops on him, he’s gonna use it.”

Jeff Thiel also had a thing for knives, said Heather Thiel, who has memories of him sitting in a recliner with sharpening tools and blades. Because he worked at a foundry, she said she came to believe he easily could have brought a murder weapon to work with him and melted it down.

And there was this comment, which she said her father made the day Togstad and Mumbrue were killed: “It’s funny how you can get away with murder these days.”

A suspect from the start

The murders were brutal. They were found in the bedroom of Togstad’s farmhouse. Mumbrue, 34, was stabbed 27 times, according to a forensic pathologist who testified at Haase’s trial. His throat had been cut. Togstad, 23, had been stabbed once in the chest and appeared to have been sexually assaulted.

Even Togstad’s dog, a terrier named Scruffy, was fatally stabbed.

According to one of the original detectives who investigated the case, authorities focused on Jeff Thiel as a possible suspect early on.

“With his background and build and strength, he was certainly a person that we had to go after,” said Al Kraeger, who retired from the Waupaca County Sheriff’s Department six years ago.

But physical evidence soon cleared those suspicions for law enforcement, said Capt. Nick Traeger of the Waupaca County Sheriff’s Department. In 1996, just as DNA was revolutionizing forensic sciences, an analysis eliminated Jeff Thiel as the person who sexually assaulted Togstad, Traeger told “Dateline.”

A blood sample taken from the clothes he was wearing at the time of his suicide did not match semen found on Togstad, the captain said.

Heather Thiel said she knew none of this. And as the years passed and no arrests were made, she said she would tell anyone who would listen that her father was probably responsible for the murders.

In 2010, she saw a billboard authorities had put up seeking information about the killings and called the listed phone number.

According to a law enforcement summary of the interview that followed, Heather Thiel told investigators about her father’s habit of killing animals and his casual comments about murder. She told them that he’d wanted to be with Togstad and had an obsession with knives. And she told them that he’d taken his own life after fleeing from law enforcement.

“I had spent my whole life thinking my dad did this and maybe I’d get answers,” Heather Thiel said. “But then, literally nothing came of it.”

One of the investigators who interviewed Heather Thiel, Mike Sasse of the Wisconsin Division of Criminal Investigation, said that they did nothing with her information because he already knew that DNA had eliminated Jeff Thiel as a suspect years earlier.

“Now, could he have been a peripheral character” in the murders? Sasse added. “At that time, yes, he could have been.”

A confession from a night in a ‘drunken stupor’

More than a decade passed and still, there were no arrests.

Then, on April 8, 2022, Heather Thiel found herself speaking to law enforcement — again. This time, her mother was present for the interview, according to a case report from the Wisconsin Division of Criminal Investigation. Authorities were interested in obtaining their DNA and learning about the family’s allegations against Jeff Thiel, the report states.

During the interview, Heather Thiel said she raised the same concerns that she’d detailed for Sasse in 2010. She provided a buccal swab, she said, as well as access to a family tree she’d been developing on a genealogy site.

“She turned on her profile, and it was like the Christmas tree lit up,” said Traeger, one of the investigators who interviewed her.

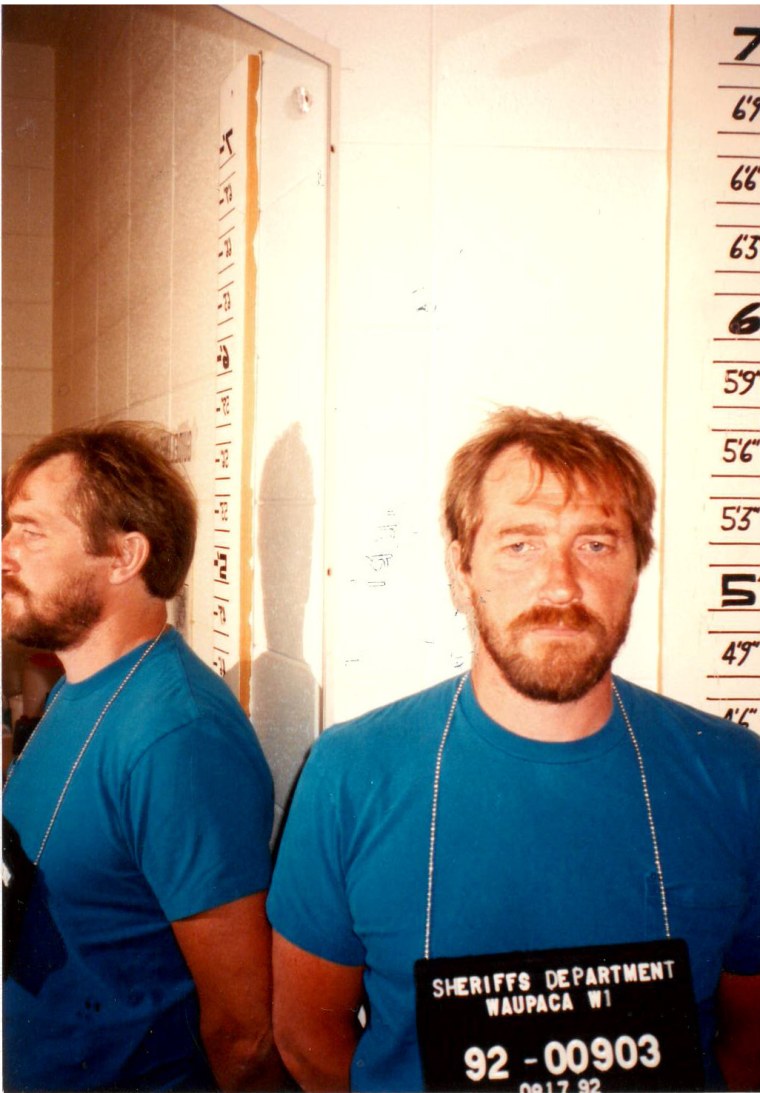

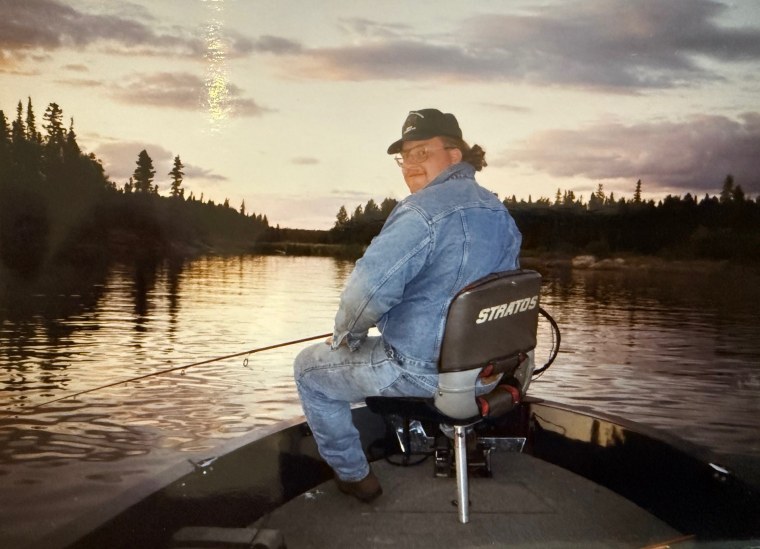

The mystery DNA obtained from the crime scene did not match Jeff Thiel, Traeger said, but it did match someone else in the family — Heather Thiel’s cousin, Tony Haase, a father of four with no criminal record who worked at the same iron foundry as Jeff Thiel.

Authorities confirmed the link by surreptitiously collecting Haase’s DNA from a pen during a traffic stop, Traeger said.

During interviews with authorities, Haase, 54, denied that he had anything to do with the murders. When one of the officers told him that his DNA was found at the crime scene, he said: “I still don’t buy it,” a video of the interview shows.

But as investigators continued to press Haase, he admitted that over the years he’d had “little clicks” — or memories — that made him wonder if he’d been involved in the killings. He said he remembered a barbell in the house — crime scene photos showed one in the bedroom — then leaving the house and vomiting outside, according to the video.

In an interview at the sheriff’s office, investigators said this latter detail was a natural human response following an extreme event.

Haase described how his father had been killed in an accident while racing snowmobiles with Togstad’s father, and how on the night the couple was killed, he was drunk and all he could think about was the accident.

“I didn’t go there to hurt nobody,” he told investigators. “I honestly can tell you that I don’t know what started, what happened, what started it all.”

Asked why it took so long for him to acknowledge what he’d done, Haase said: “Because I didn’t want it to sound like I had this planned.”

On Aug. 11, 2022, Haase was arrested for the murders of Togstad and Mumbrue. A probable cause affidavit filed in Waupaca Circuit Court said that at the time of the killings he’d been in a “drunken stupor.”

Doubt surrounds murder trial

Heather Thiel was shocked. She didn’t know her cousin well but said he didn’t seem to have a mean bone in his body.

The arrest also prompted some self-reflection.

“I was like, how could I have had it wrong?” she said. “If I was wrong about my dad and it was actually my cousin — well, sorry, you should pay for what you did.”

Jeff Thiel, however, continued to loom over the case as Haase’s trial approached.

In a pretrial hearing in May, Haase’s attorneys said that because Jeff Thiel’s genetic profile had not been excluded from all of the blood evidence gathered at the crime scene, they should be able to argue at trial that he was still a possible suspect in the murders.

Prosecutors objected, but the judge sided with the defense, a transcript shows. So the state asked to exhume Jeff Thiel’s remains to carry out additional DNA testing — a process that Waupaca County District Attorney Kat Turner said would allow them to exclude him from physical evidence gathered at the scene.

In June, Jeff Thiel’s remains were disinterred from a Waupaca County cemetery.

“The DNA analyst worked on nothing but that until he had the analysis complete,” Turner told “Dateline.” “And again, excluded Jeff Thiel from all of the blood evidence that was available.”

In the pretrial proceedings, Haase’s lawyers sought to bar that evidence because they said they didn’t have time to prepare a response before trial, which was scheduled to start two weeks later. Prosecutors again objected, Turner said, but the judge ruled that if the trial started as scheduled, the state would be prohibited from presenting any DNA evidence related to Jeff Thiel.

Instead of delaying the trial and challenging the ruling — a process that could have taken years, Turner said — the prosecution forged ahead. Turner said that decision was made after consulting with victims’ families and weighing the challenge of trying an old case in which investigators and scientists were becoming sick or dying.

‘Somebody who has no conscience’

Haase’s trial began in July in a Waupaca County courthouse. His attorneys argued that Haase’s confession had been coerced — investigators planted false memories in an hourslong interrogation — and they said the male DNA found on Togstad’s body had been degraded by years of testing and storage.

As evidence of Jeff Thiel’s involvement in the murders, attorney John Birdsall cited an apparent motive — Tanna had rejected Jeff Thiel’s advances — and he linked Jeff Thiel’s habit of killing pets to Scruffy’s death.

“This was killed by somebody who has no conscience, who has absolutely no problem killing anything in its path,” he said in his closing argument. “That’s Jeff.”

Amy Ohtani, the assistant attorney general who also prosecuted the case, described the defense’s strategy as an effort to “weave together a fantasy to keep you from paying attention to the actual evidence.” The DNA had been properly collected, preserved and tested, she said in her closing argument, and the idea that Haase’s admissions were false was a “distraction.”

Jeff Thiel, she said, was the “perfect scapegoat.”

At trial, she said, he’d been described by family members as an “absolutely terrible person” — but wasn’t there to defend himself and there was no evidence actually linking him to the crime.

“Jeff Thiel sounds like he was a terrible guy,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean he killed Tim and Tanna.”

On the fourth day of deliberations, the jury acquitted Haase of the murders.

For his cousin, that decision was the right one. Heather Thiel had come to doubt the forensics that excluded her father from the murders and linked her cousin to them, she said, and she believed Haase had been coerced into making a false confession.

Although the trial produced no definitive answers, Heather Thiel said, the proceedings prompted her to return to a long-held position about who killed Mumbrue and Togstad.

“Until proven otherwise, I will always believe it’s my dad,” she said.