A little over a year ago, Manchester United sacked Erik ten Hag … just a couple of months after a monthlong review that resulted in the club opting to keep Ten Hag as manager. United had just lost to West Ham, 2-1.

“Sources told ESPN that United bosses made the decision to sack Ten Hag after losing faith that the Dutchman would be able to turn things around after a poor start to the new campaign,” ESPN’s Rob Dawson wrote at the time. “After earning just 11 points from nine league games, there are already concerns that United are too far adrift to qualify for next season’s Champions League.”

United had finished in eighth the season before, and were sitting in 14th. Then, they hired Ruben Amorim and ultimately finished last season in 15th.

Their points-per-game declined from 1.2 under Ten Hag to 1.0 under Amorim, as did their per-game goal differential: minus-0.3, down to minus-0.4. Despite performing even worse than the level of performance that warranted firing the previous manager, United stuck with their guy.

It seemed like it might finally be paying off as they rode a five-game unbeaten streak in all competitions through October and November — until they lost, 1-0, on Monday at home to Everton, who played a man down for 75-plus minutes.

Through 12 games, Manchester United are in a four-way tie for 10th place. We’re a year and a day since Amorim’s first game with United — they’ve played a full season’s worth of Premier League matches and then one more. And so, a question: Are Manchester United any better than they were a year ago?

– Missed chance for United, Amorim on dismal night vs. Everton

– Ranked: All 64 national teams that can still win the 2026 World Cup

– Ranked: Europe’s 10 worst transfers from this summer, so far

What has changed at United under Ruben Amorim?

Tactical formations are mostly meaningless: one man’s 4-3-3 is another man’s 4-2-3-1 is another man’s 3-4-3, after all. But with Amorim, it’s impossible to disentangle his ideas about the way the game is meant to be played and the first number in that formational shorthand.

“I won’t change my philosophy,” he said, back when United were struggling in September. “If they [United hierarchy] want it changed, you change the man.”

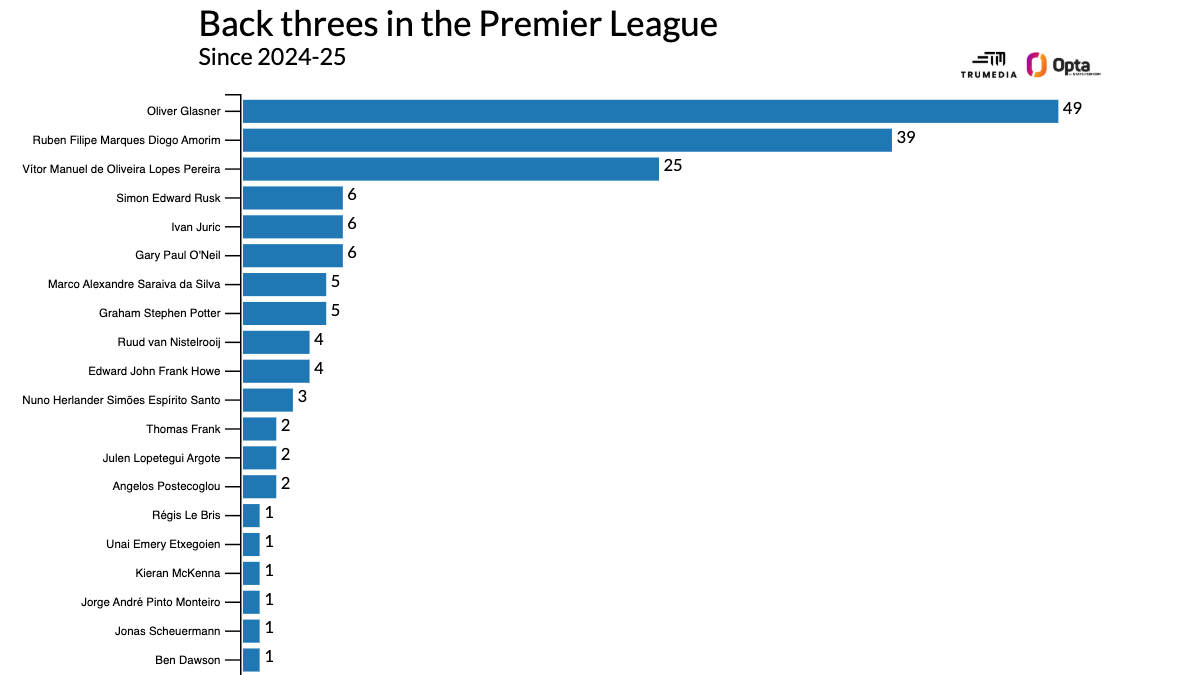

Per Stats Perform’s data, Amorim has started all 39 matches at United with either a 3-4-3 or a 3-4-2-1. Since the start of last season, only Crystal Palace manager Oliver Glasner has stuck with a back-three defense more often:

While Amorim’s formation has remained the same and he claims his philosophy will never change … well, something has changed this season. Last year, the defining characteristic of Amorim’s United was how slow and ineffective they were with the ball.

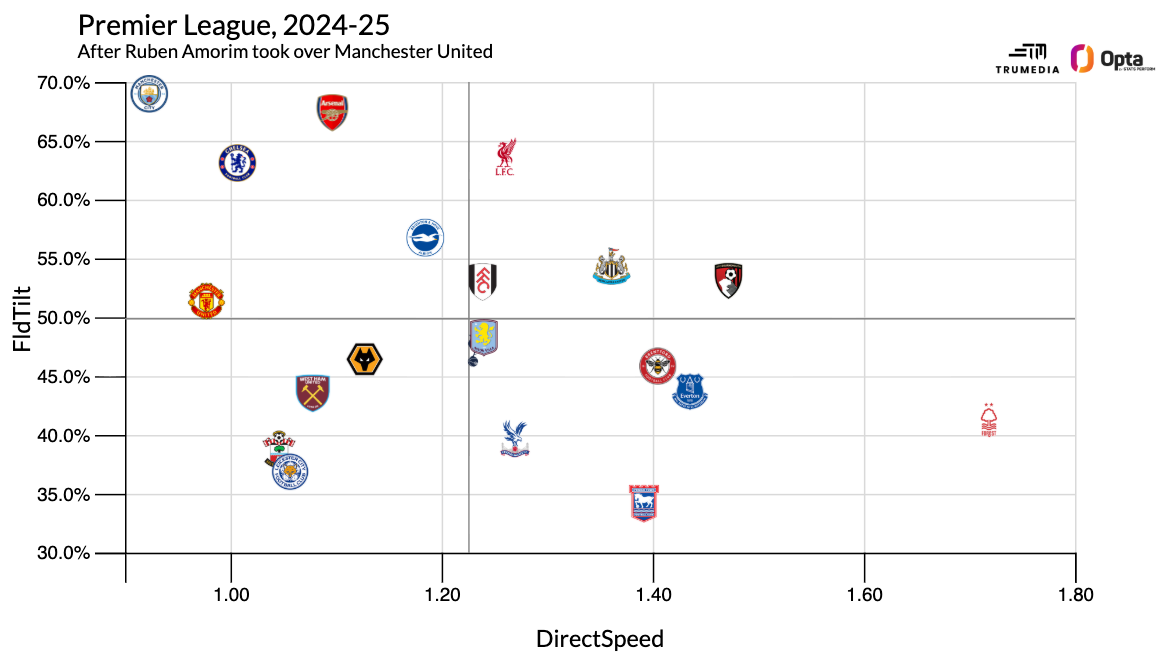

After Amorim took over, United moved the ball up the field with an average speed of 0.98 meters per second — the second-slowest mark in the league after Manchester City. Except unlike City, they weren’t slowing things down once they got into the attacking third; no, they were mostly just recycling the ball around in their own half.

Generally, you can play slowly and dominate territory or play quickly and let the ball come into your own third a little more often — either one can be effective. If you can play quickly and dominate territory, then congrats, you’re probably a team managed by Jurgen Klopp or Arne Slot. But if you don’t dominate territory and you don’t play quickly, then you’re just not going to win many soccer games.

Uncoincidentally, as you’ll see in this graph comparing speed of play with final-third possession, two of last season’s relegated teams fell into the slow-and-not-dominant quadrant, as did West Ham and Wolves, two of this season’s most likely relegation candidates. Amorim’s United, too, were dangerously close to slipping down there, too.

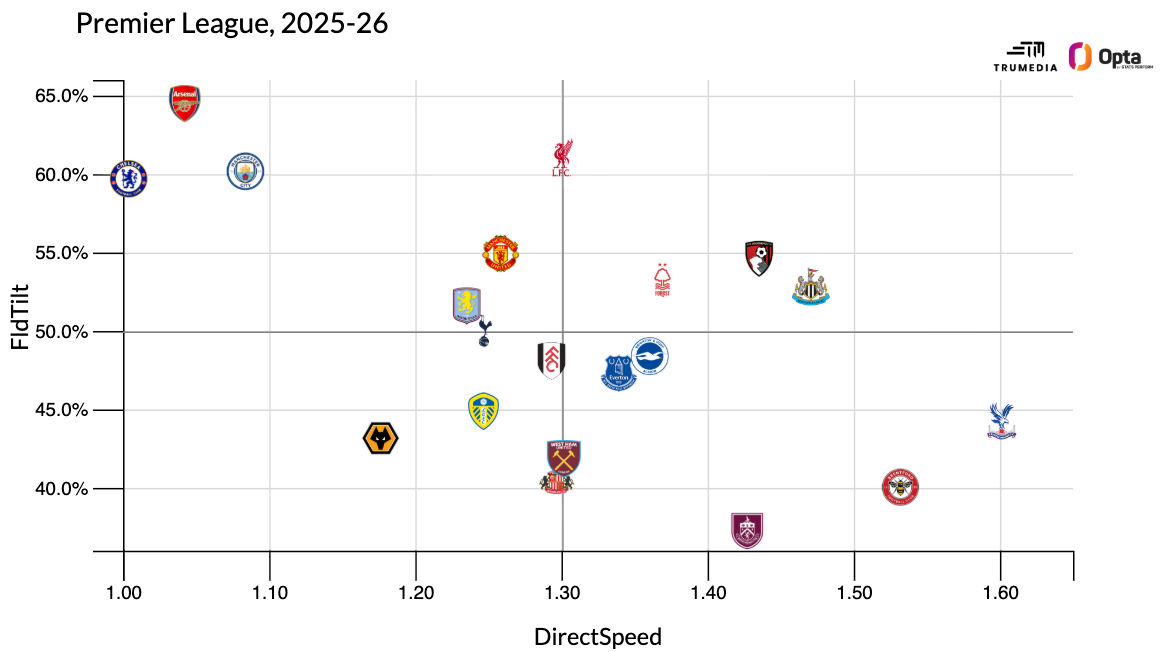

However, that’s no longer true this season. Here’s the same chart, through the first 12 matches of this year:

Amorim’s team is still controlling roughly the same amount of territory, but they’re doing it with a much higher-tempo approach with the ball. And that’s made the team significantly better. Through 12 games, compared to the 27 under Amorim in 2024-25, they’re averaging 0.5 more points per match, and their goal differential has improved by 0.4 points per game. Over a full season, that’s about 19 more points and a 15-goal differential improvement.

How much better are they? And how sustainable is the improvement?

We’ll start with their adjusted goal differential, the blend of 70% expected goals and 30% goals. By this performance metric, they’re a mirror image of last season — in a good way. Last year under Amorim, their adjusted goal differential was minus-0.16. This year, it’s up to plus-0.20. Through 12 matches, that’s good enough for seventh-best in the league.

Just looking at the offensive end, their adjusted goals scored is 1.67 per game, up from 1.29 per game under Amorim last season. On the other side of the field, their adjusted goals conceded has gotten ever-so-slightly worse, up to 1.46 from 1.45.

However, the tiny trade-off has been worth it. By being less conservative on the ball, it has made United more vulnerable defensively, but it has boosted the attack by an even greater degree.

Figuring out the proper balance for these trade-offs and then actually implementing them on the field is most of what coaching is, and Amorim has shown improvement from one year to the next. That’s one of the benefits of hiring a young manager; they can get better in the same way young players do.

Of course, it’s impossible to disentangle Amorim’s coaching from the performances of the players he’s coaching. And the major difference from this season compared to last season is that all of United’s forwards are different.

Bryan Mbeumo has played almost every minute of every game, while Matheus Cunha and Benjamin Sesko have had their injury issues but they’ve each started at least half of the matches. United are a better team this season because they’re better at attacking this season. And the simplest explanation for why they’re better at attacking: They have a bunch of new attackers.

Now, does Amorim deserve credit for changing the way United play?

The one area where you can dial into tactical decisions and say “this is on purpose, not just an artifact of the decisions all of the players are making on the fly” is on goal kicks. And United are playing two-thirds of their goal kicks long this season, compared to 45% last season.

Their goalkeepers, too, are launching non-goal kicks 60% of the time, nearly double last season’s rate of 32%. Some of that is because wannabe-Andrea-Pirlo André Onana is no longer in goal, but it syncs up too well with the general change in approach. It appears this is all happening on purpose.

But will it last?

United have had a number of things go in their favor so far this season.

The first: They went up a man in the fifth minute against Chelsea. Of course, Casemiro then got sent off right at the end of the half, but they’d already gone up 2-0 and still had the advantage of playing against more-tired opposition on a suddenly much bigger field at 10 vs. 10, and won.

And then, against Everton, Idrissa Gueye smacked his own teammate, and United got to play up a man for 80 minutes. They, of course, lost, but they’ve spent a ton of time against 10 men this season, and that’s allowed them to rack up shots and expected goals totals they otherwise wouldn’t have.

On top of that, they’ve also won three penalties and conceded zero. While penalties are not totally random, United are currently on pace to finish the season with nine or 10 penalties won, and zero against.

That’s very unlikely to happen, and if we strip out penalties from those adjusted numbers we’ve already touched on, then their differential drops down to plus-0.04. In the nine games that got Ten Hag fired last season, United were at plus-0.01. Given all of United’s minutes with an extra player this season, it’s fair to say that they’re playing at pretty much the same level they were when Amorim joined the club.

The major question facing United and their manager going forward, then, is: Will he continue to improve? Things are in a much better place than they were at the end of last season, but that’s largely because the team was even worse under Amorim last season than they were under Ten Hag.

With a dogmatic coach like Amorim, there’s definitely an argument that you need to get worse in order to get better. I wrote about this when they hired him: Perhaps there would be growing pains when he tries to implement his ideas, but that doesn’t mean there won’t be a longer-term payoff.

Based on the evidence, though, I still don’t think I’d turn my club over to a manager who, although he has shown some ability to evolve, still requires a very specific set of players to play his preferred formation. It’s unlikely that the next coach at United also wants to use wingbacks, three center backs, and two pinched-in attacking midfielder-types instead of wingers.

There hasn’t been enough improvement — especially when you try to disentangle changes in personnel from genuine manager-driven gains — to say it’s worth reshaping the squad in Amorim’s vision. That’s especially true when doing so means that you’d have to reshape the squad again if he doesn’t work out.

The other thing that would give me pause is that much of the improvement has been achieved by making the team older. Both of the starting midfielders, Casemiro and Bruno Fernandes, are in their 30s. Both Mbeumo and Cunha are halfway into their primes. The average age of United’s team last season, when weighted by minutes played, was 25.5 years; this season it’s up to 26.5. That makes United older than both Arsenal and Manchester City; the current roster is a win-now type roster, and this team still isn’t close to winning now.

At the same time, they’ve had a tough schedule to start the season. They don’t play any of the still-presumptive top four (Arsenal, City, Chelsea, and Liverpool) until midway through January, when they play City and Arsenal on back-to-back weekends. They could go on a run, and things could improve even without the penalties and red cards boosting their performance.

Ultimately, though, Amorim does deserve some credit. He has guided United to a place that I really can’t remember them reaching. They’re not a complete disaster, where everything is on fire and everyone’s job is at risk, every weekend. And they’re also not convincing anyone that Manchester United actually are back, ready to challenge for the major trophies that they always used to win.

Manchester United are neither good, nor bad now. What Amorim has made them is … average.