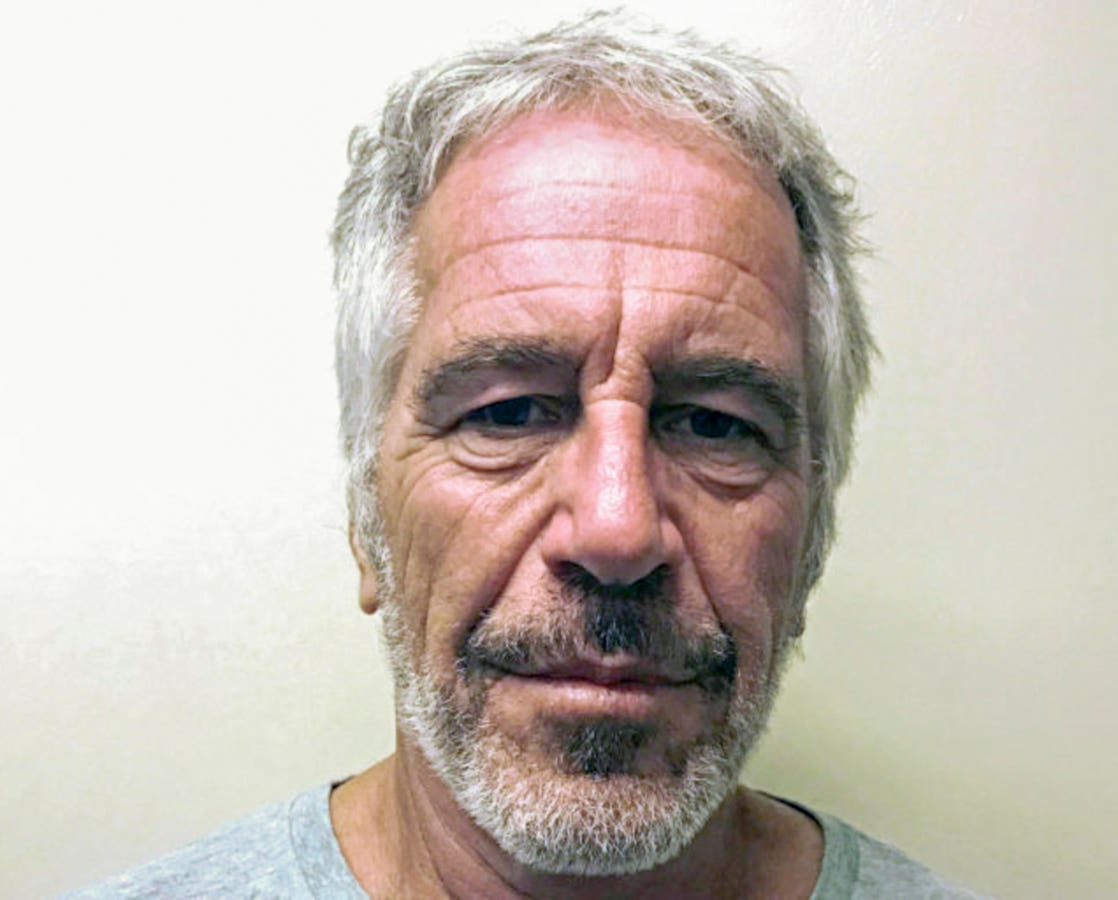

The Epstein ‘missing video” explained by digital forensics experts.

When reports emerged of “missing minutes” in Jeffrey Epstein’s jail surveillance video, the story seemed to suggest something sinister. After all, how could crucial surveillance footage be incomplete during such a significant event? But this case offers a perfect example of why understanding digital forensics is essential in modern litigation, and why the most dramatic explanations aren’t always the correct ones.

Two former FBI Senior Forensic Examiners, Stacy Eldridge and Becky Passmore, decided to conduct their own analysis when they felt media reports lacked sufficient technical detail. Their findings suggest not a cover-up, but rather the complex reality of how digital video works in the modern surveillance age. However, their analysis also reveals an important limitation: without access to the original raw surveillance files, even expert forensic examiners cannot be completely certain about what occurred.

Understanding Work Product vs. Raw Evidence

When digital forensic examiners need to share surveillance footage, they rarely share the original files straight from the camera system. Instead, they create what’s called a “work product.” This happens because raw footage often requires specialized and sometimes proprietary software and equipment for viewing. Think of it like the difference between a photographer’s original camera files and the edited photos they share publicly.

The FBI’s released video falls into this category. As Eldridge and Passmore discovered through their analysis, “This is not a ‘raw’ file. It’s not evidence. It’s work product. Something someone would make for easier viewing and sharing.”

Understanding this distinction is vital because work products undergo processing that can create timing discrepancies without affecting the underlying evidence. It’s the difference between the original surveillance recording and a presentation version designed for public release. However, this also means that definitive conclusions about tampering require access to the original files that the experts did not have.

How Modern Digital Forensics Works

Digital forensics operates much like traditional detective work, but instead of fingerprints and DNA, experts examine metadata, file structures and digital signatures. Metadata serves as a digital fingerprint that reveals a file’s complete history: when it was created, what software processed it, how many times it was saved, and even details about the computer that handled it.

Eldridge and Passmore employed the same rigorous techniques used in criminal investigations. Their analysis revealed several important technical details. The video was processed using Adobe Premiere Pro, as evidenced by a project file named “mcc_4.prproj” and metadata showing it was created from two separate source files. They even found a partial username, “Mjcole~1,” providing insight into who processed the footage.

This level of detail matters because it allows forensic experts to reconstruct how the final video was created and identify what changes may have occurred during processing. However, the experts were careful to note the limitations of their analysis without the original source material.

Decoding Three Types of Time Discrepancies

The experts identified three distinct issues that created timing discrepancies. Understanding each category helps explain why timing problems don’t automatically indicate evidence tampering, while also showing why definitive conclusions require more complete information.

1. The System Reboot Gap In The Epstein Video

The first category involves the acknowledged system reboot. Surveillance systems, like all computers, require periodic maintenance. The jail’s system underwent routine maintenance around midnight, creating a 62-second gap in recording. The experts pinpointed this precisely: “Nightly reboot start timestamp 8/09/2019 11:58:58 last number appeared” and “nightly reboot end timestamp 8/10/2019 12:00:00 AM first number reappeared.”

This gap represents actual missing time, but it’s the kind of planned maintenance that occurs in surveillance systems nationwide. The key question isn’t whether this gap exists, but whether it occurred naturally or was deliberately timed to coincide with significant events. Without access to system logs and maintenance records, this question cannot be definitively answered.

2. Content Edited from the Beginning of The Epstein Video

The second category involves edited content from the beginning of the file. The experts found evidence that approximately 3 minutes of content appears to have been removed from the very start of the video file. However, they emphasized an important caveat: “The 3 minutes not accounted for from the file 2025-05-22 16-35-21.mp4 was likely cut from the beginning of the file. This is an assumption based on time calculations based on the metadata we were able to retrieve. This is not definitive as we do not have the original videos that were used to create video1.mp4.”

This finding illustrates both the power and limitations of forensic analysis. The location of missing content matters enormously. Content removed from the beginning of a file often suggests routine editing to focus on relevant timeframes, similar to how a documentary editor might trim unnecessary footage from the start of a scene. Content removed from the middle of a timeline, particularly during critical moments, would raise much more serious questions about tampering.

Yet the experts’ honest acknowledgment of uncertainty demonstrates scientific integrity. They found patterns suggesting routine editing, but cannot eliminate other possibilities without the original files.

3. Dropped Frames Throughout the Epstein Video

The third category involves dropped frames, a concept that requires careful explanation because it’s often misunderstood. When video systems encounter processing limitations, whether due to hardware constraints or file compression needs, they employ a technique called frame dropping. Instead of losing entire sections of video, the system removes individual frames scattered throughout the recording.

Think of this like removing every 100th word from a novel. You lose some detail, but the story remains coherent and readable. The experts found approximately 12,000 individual frames were dropped during processing out of more than 1.2 million total frames, creating a loss rate of 0.97%.

“Dropped frames account for the missing 6 minutes and 34 seconds we thought we discovered. Loss rate is less than 1%,” the experts concluded.

This distinction between dropped frames and missing video segments is necessary for understanding evidence integrity. Dropped frames represent a technical limitation that doesn’t compromise the evidentiary value of surveillance footage, while truly missing video content could suggest deliberate tampering. However, distinguishing between routine frame dropping and intentional deletion requires access to the original processing logs and source files.

Epstein Video: Why Technical Context Prevents Misinterpretation

The Epstein video case demonstrates why technical literacy matters in interpreting digital evidence. Without understanding how video processing works, timing discrepancies can appear suspicious when they’re actually routine technical artifacts.

Consider how the initial reports interpreted the evidence. WIRED reported “2 minutes and 53 seconds” of missing footage.. However, without the proper forensic context, this was presented as potentially significant missing content rather than normal processing artifacts.

As Eldridge and Passmore noted, they were motivated to conduct their analysis after being “not satisfied with the reporting on the metadata involved in this case.” Their expertise allowed them to distinguish between technical processing effects and actual evidence problems, though they acknowledged the inherent limitations of analyzing processed files rather than original evidence.

The confusion stemmed primarily from two factors: the FBI labeling processed video as “raw footage,” creating expectations that this was unaltered surveillance content, and normal frame dropping during video compression creating timing discrepancies that seemed suspicious without technical context.

The Critical Limitation: Why Raw Footage Matters

While the expert analysis provides valuable insights, it also highlights a fundamental principle of digital forensics: the most definitive conclusions require access to original, unprocessed evidence. As Eldridge and Passmore honestly acknowledged, their analysis was limited by working with processed files rather than the original surveillance data.

This limitation doesn’t invalidate their findings, but it does place them in proper scientific context. The experts found no evidence of tampering and identified plausible technical explanations for all timing discrepancies. However, for these conclusions to move from “highly probable” to “certain,” forensic examiners would need the FBI to provide the original raw surveillance files for examination.

This distinction matters because it demonstrates both the power and the limits of forensic analysis. Expert examination can rule out many conspiracy theories and provide strong evidence for technical explanations, but absolute certainty in digital forensics often requires access to complete evidence chains that may not always be available.

Balancing Skepticism with Technical Reality

The Epstein video analysis ultimately reveals that the most complex conspiracy theories can often have the simplest explanations. In this instance, timing discrepancies that seemed suspicious were most likely routine technical artifacts created during normal video processing.

This doesn’t diminish the importance of thorough investigation or the value of healthy skepticism about official accounts. Rather, it demonstrates why proper technical analysis is essential for distinguishing between genuine evidence problems and normal digital processing effects. It also shows why honest scientific analysis includes acknowledging limitations and uncertainties.

The case serves as a reminder that in today’s world, technical literacy is becoming as important as traditional investigative skills. Understanding how digital systems work helps us ask better questions, interpret evidence more accurately and avoid drawing dramatic conclusions from routine technical processes. It also helps us understand when additional evidence is needed for complete analysis.

As Eldridge and Passmore noted, they conducted their analysis because “We’re both former FBI Senior Forensic Examiners and we’re here to share the facts.” Their work exemplifies how proper forensic analysis can cut through speculation and provide evidence-based conclusions, while also demonstrating the scientific integrity to acknowledge when complete certainty requires additional evidence.