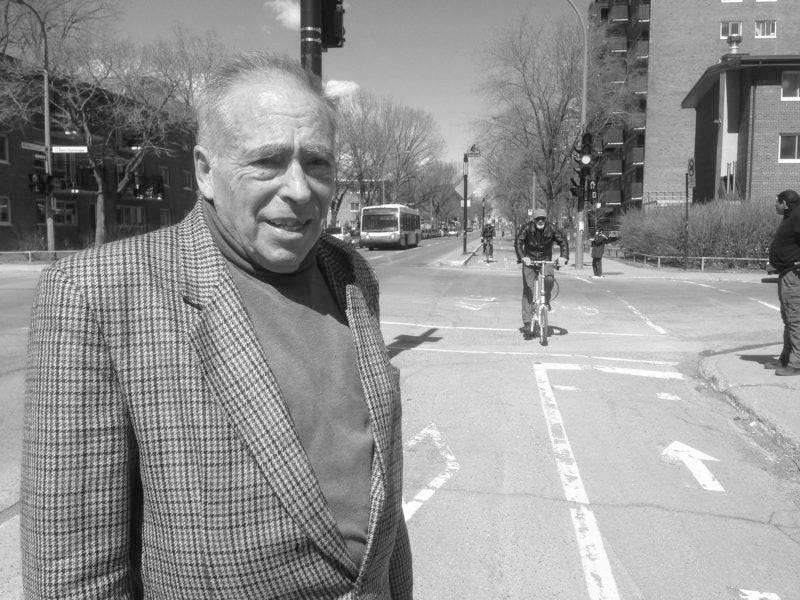

“Bicycle Bob” Silverman beside the cycleway named for Claire Morissette, the cofounder—with Silverman—in 1975 of bicycle-advocacy group Le Monde à Bicyclette

Carlton Reid

A major cycleway in Montreal, Canada, is to be named in honour of one of the city’s foremost cycle campaigners, Robert Silverman, who died in February 2022, aged 88. Mayor of Montreal Valérie Plante will open the Réseau Express Vélo Robert-Silverman—or the Robert Silverman Express Cycleway—on Monday, 8 September.

The honor was bestowed on Silverman by Montreal’s Recognition Advisory Committee. The existing cycleway was the the REV Saint-Denis/Berri/Lajeunesse cycleway. Several years earlier the city named one of its cycleways for Claire Morissette who, with Silverman, founded the cycle campaign group Le Monde à Bicyclette in the 1970s.

The largest city in Canada’s Québec province, Montreal is considered the best cycling city in North America. It is where, in 2009, modern big-city bike-share schemes took hold, and it has more than 400 miles of cycleways, 150 miles of them separated from motor traffic.

Many of the campaign tactics employed by Le Monde à Bicyclette are still used by advocacy groups around the world, including “die-ins.”

Montreal’s first such demonstration–modeled after play-dead protests in the Netherlands from earlier in the 1970s–used black humor, urging protestors to “Come die-in with me.”

A placard at one of these 1970s die-ins demanded “vélo pour la vie”—“bicycle for life.”

“When I became a bicycle advocate [in the 1970s], for the first time I had a reason to live,” the English-speaking Silverman told me in 2017.

“I have dedicated my life to making the world a better place via a simple solution: the bike!”

Militant ecologist

Le Monde à Bicyclette—literally, “The World of the Bicycle,” or Citizens for Cycling, or just MAB—was a motley collection of francophone nationalists and anglophone anarchists who, after several years of campaigning, successfully persuaded the left-leaning politicians of Montreal to provide for people on bikes.

One of the key asks of the anti-automobile activism group was a city center curb-protected cycleway, and this was built in 2007, replacing a car lane. It was named for Morissette, who had died from cancer earlier in the same year. Signs on the Piste Claire-Morissette state proudly that she was a “militante écologiste.”

Robert Silverman as Moses, with the “Bicycling 10 Commandments” in a 1970s media stunt.

Robert Silverman archives

Morissette was the creative brains of the organization; Silverman was the lead actor. To protest at the lack of a safe bridge crossing for cyclists over the St. Lawrence River, he dressed up as Moses and, clasping the Ten Bicycle Commandments (“Thou shalt not Kill, Thou shalt not Pollute . . .”), he attempted in vain to part the “Red Sea” for a gaggle of waiting cyclists. The local media loved this and similar stunts the group pulled, such as attaching wings to bicycles, attempting to fly over the river, and towing bicycles on rafts behind canoes. In 1990, Montreal built a pedestrian and cyclist bridge and added bike lanes to other bridges.

Perhaps because many members were comfortably bilingual and Silverman was a poet at heart, MAB used words as weapons, although always humorously. MAB’s guerrilla protesters were “vélo-Quixotes,” “vélo-holy rollers,” and “vélorutionaries”; they fought against “autocracy” using “cyclodramas.”

Silverman wrote poems and songs for the group’s newsletter, such as this one from 1976:

Forward bicycles

Listen to the echoes

The future of bicycles

It’s the end of cars

Le Monde à Bicyclette Wants to change the planet

Le Monde à Bicyclette Will save the planet

It’s the end of the scourge

No more plots

No more pollution

For it is the revolution.

Robert Silverman with a Le Monde à Bicyclette flag in the 1970s.

MAB

Cyclo provocations

In the 1970s, the group’s longest-running cyclodrama was when activists carried bulky items onto Montreal’s metro—a ladder, skis, a papier-mâché hippopotamus—while those with less bulky bicycles were refused access.

Claire Morissette with Robert Silverman, 1977.

Robert Silverman archive/MAB/Tom Berry

After three years of these “cyclo-provocations,” MAB won the subway access for cyclists it had sought. MAB also constructed car-sized wooden frames for placing over moving bicycles to demonstrate how much space Montreal would save if it catered to cyclists, and not just to automobiles.

“Motorists got really mad at that,” remembered Silverman in 2017.

Always willing to suffer for the cause, Silverman was sentenced to eight days in the clink for refusing to pay a small fine levied after he was caught illegally painting a cycle lane on a residential street. (He was released after two days.)

Modern big-city bike-share schemes were born in Montreal. The municipally-owned Bixi (a portmanteau of “bike” and “taxi”) bike-share scheme was modelled on the Vélib scheme in Paris, and an earlier one in Lyon. Bixi was originally owned by the city of Montreal but losses eventually forced the company into bankruptcy.

London’s “Boris” bikes were supplied by Bixi, and they were originally exact facsimiles of the muscular machines first used in Montreal.

In a poem about Silverman, Morissette wrote that “Bicycle Bob” was “a disturber, a fanatic, an epic bikeshevik.”

“By tens, hundreds, thousands, people are proud to ride,” she added.

“You make our dreams come true, thanks to you we can breathe.”

Life

Silverman was still a bicycle advocate when I met him in 2017. I was in Montreal researching a book, Bike Boom, which was published in the same year. While still an advocate he was no longer mobile and I ferried him around Montreal in a Christiana cargo trike. He showed me the curb-protected cycleway in the Central Business District named for Morissette.

I dedicated my book to Silverman, writing:

For Robert “Bicycle Bob” Silverman and all of the other 1970s cycle advocates who tended cycling’s flame when planners and politicians were trying to snuff it out.

I sent him a proof of the designed pages. His reply took me by surprise:

“Thank you for dedicating the book to me. Reading it actually saved my life. I’m going blind with macular degeneration which started a few years ago, which was combined in early October with a stroke. Life has been very hard; so bad that I cannot ride a bicycle any more, cook, or do other very simple tasks. I was prepared to take my own life, but changed my idea after reading your dedication.

“This is true, not an exaggeration. In Quebec, dying with dignity is legal … But since receiving your dedication [my mind has] changed.”

It was wonderful that Bicycle Bob lived until he was 88, and I was very touched by his candour. He granted his permission at the time for me to tell this particularly sensitive tale.