“The signs of the ocean in distress are all around us”, said Peter Thomson, Special Envoy of the Secretary-General of the United Nations for the Ocean, at the conference in Nice, France last week. “The time of debating with the denialists is over”. This statement of intent backed a slew of agreements that aim to remedy the damage already done to our oceans and prevent further harm. Overfishing, deep-sea mining, pollution with a focus on plastic, with acidification and other threats associated with climate change were on the agenda of global problems to eliminate. We all knew these problems were bad and getting worse, but a new report reveals that we continue to race past critical tipping points without even realizing it.

For a couple of decades now, shellfish have been unable to make their shells. This was localized and weird; now its global and dangerous.

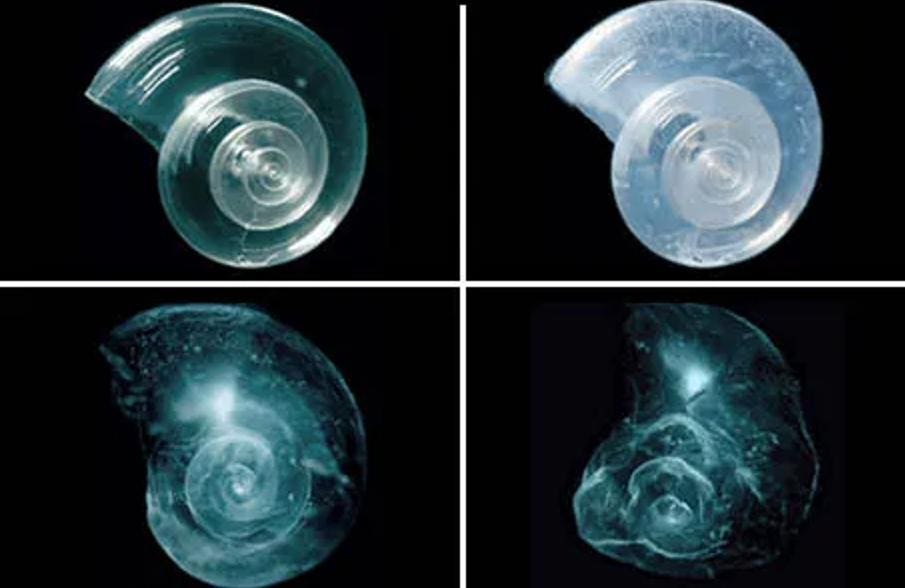

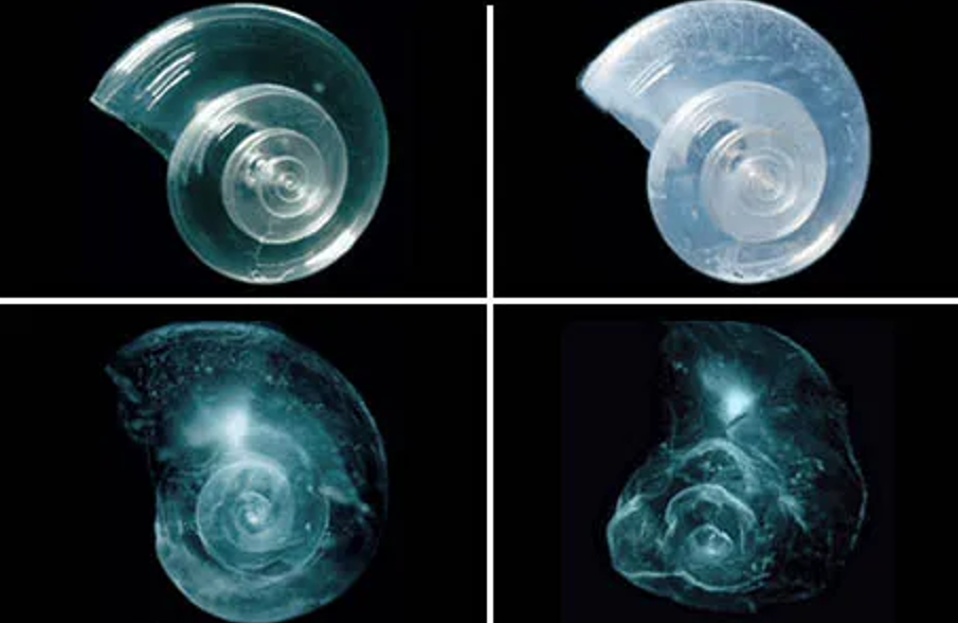

Lab tests show the effects of high-acidity environments on Pteropods. They can dissolve in 45 days. … More

Ocean Acidification

When carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere about 25% of it will end up in the oceans where it dissolves, and makes the water more acidic. This change in pH is as drastic a change in the environment as temperature or any other abiotic factor. This new aquatic chemistry isn’t something to which organisms can adapt, and they’re correspondingly suffering. Comparing certain species of shellfish with their pre-Industrial Revolution conspecifics (members of the same species) collected in 1875 by the crew of the HMS Challenger, we see that they’re up to 76% thinner than their ancestors. This was observed with a 40% increase in acidity. By 2100 the oceans will be 150% more acidic than at present.

This “Evil Twin” of Climate Change has been underestimated. We’re realizing that we’ve crossed a significant tipping point five years ago. Ocean Acidification is so dramatic that shellfish larvae can’t form their shells. We now understand that the acidity interferes with the creation of calcium carbonate that’s need to form the shells of these organisms. Oyster farmers from the Pacific Northwest have observed this since at the early 2000s. Coral, Crabs, and Krill are some of the organisms that have been specifically studied and seen to be struggling. It would be sad in and of itself if we couldn’t enjoy delicious crabs and mussels anymore, but this is worse when we consider that it signals a pending, global ecological catastrophe.

Tropical fish and turtle in the Red Sea, Egypt

Small organisms are foundational for the wider food web as without krill we don’t have whales, without mollusks we don’t have otters, so on. Without coral we can’t have the coral reefs that act as oases of life in the wider stretches of bare ocean. The threat to marine life isn’t just the direct loss as such; the rest of the world’s life depends on the oceans.

Legacy Carbon Must Be Addressed

When discussing how to reach net-zero, we’re figuring how to balance our carbon emissions with carbon sinking. If we have a factory that has to make fertilizer and it released greenhouse gases, but then old growth forests absorb and sequester this carbon, then it balances out. The net release of carbon is zero. This is an important milestone that most nations hope to achieve by 2050. The leading ways to do this include preserving forests to absorb carbon emissions while generating power with cleaner means. Release less and absorb more until the emissions balance with the sequestration.

What about all the carbon that will be released up until that point?

Ocean Carbon Cycle

Why is this happening?

We’ve been abundantly releasing carbon since the Industrial Revolution. Even with man-made global warming being hypothesized in the late 1800s, it’s taken a long time for us to feel its effects. Part of this is because significant amounts of carbon dioxide get absorbed into the oceans, from atmosphere to ocean surface, removing its warming potential. The oceans are so vast that as of 2010 they were storing about 16 times as much of carbon as makes up all living plants and animals on earth. This quantity is 60 times the amount that was in the atmosphere before the Industrial Revolution.

The oceans will have a saturation point at which they can’t absorb more carbon. That can be a concern eventually but don’t worry, that won’t happen until about a pH of 7.5. The majority of marine life will be dead by then. How serious of a problem is this? How likely are we to reach levels where even our biggest carbon reserve can’t take it anymore? If not likely any time soon, it’s a real enough of a question that scientists are proposing a new indicator to quantify ocean acidification.

Gamma Subscript CO2

In this paper published in May of this year, scientists propose a new variable (γCO2) to represent the absorption potential of the oceans. This is needed because as stated, we have pumped so much carbon into the atmosphere, which in turn absorbs into the oceans, that we need new math to do future calculations. Without modifying our current trajectory, we could reach a pH of 7.8 by 2100, which would be comparable to 14-17 million years ago when our planet was in the midst of an extinction event.

The capacity for the oceans to absorb carbon dioxide decreases as it absorbs more carbon.

Direct Ocean Capture Solves Multiple Problems

The idea of Direct Ocean Capture (DOC) is similar to Direct Air Capture (DAC). With DAC, big fans suck in air and filter out the CO2. Direct Ocean Capture is another form of Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) that uses electrolysis and filters to tackle legacy carbon at scale. With DOC we remove CO2 from the atmosphere as well as the oceans and in doing so address the problems of ocean acidification. DOC plants can be installed near desalinization plants for added efficiency, or in areas where the waters are known to be less alkaline. Targeted applications that benefit the entire oceans and atmosphere in turn. Projections have it cost competitive with DAC within the next couple of years. Given the legacy carbon problem and the amount of it that’s in our oceans, it’s a logical and scalable strategy. This industry is ripe for investment as its efficacy has been demonstrated, and the need exists. I anticipate we’ll hear more about it in the coming years as tropical marine ecosystems collapse and people try to undo the damage. I’d prefer we get ahead of it.