Certain natural plant compounds can interfere with nutrient absorption or cause symptoms in sensitive people, but preparation, balance, and diet diversity usually shift the equation toward benefit.

The Rise of Anti-Nutrients in the Wellness Conversation

For years, public conversations about vegetables were dominated by pesticides, particularly the commonly referenced “Dirty Dozen” list of produce most likely to carry residues. More recently, attention has shifted toward the vegetables themselves, specifically the compounds they naturally contain. Once little-known outside nutrition science, oxalates, lectins, and similar substances are now widely debated in podcasts, YouTube videos, and wellness blogs. According to Google Trends, searches for “oxalates” have risen nearly fivefold since 2018, with distinct spikes following viral posts and influencer commentary. Social media has played a key role in pushing the concept of “anti-nutrients” out of academic discussions and into mainstream wellness culture, where the wellness economy often thrives on simplified narratives of “good” versus “bad” foods.

It is worth noting that “anti-nutrients” is not a formal scientific category but rather a popular label applied to diverse plant compounds. While these compounds can, under certain conditions, interfere with mineral absorption or be associated with various symptoms, they also serve protective, even therapeutic, roles. The real story is about balance, context, and individual sensitivity.

Oxalates: From Spinach to Kale Chips

Fresh spinach leaves

getty

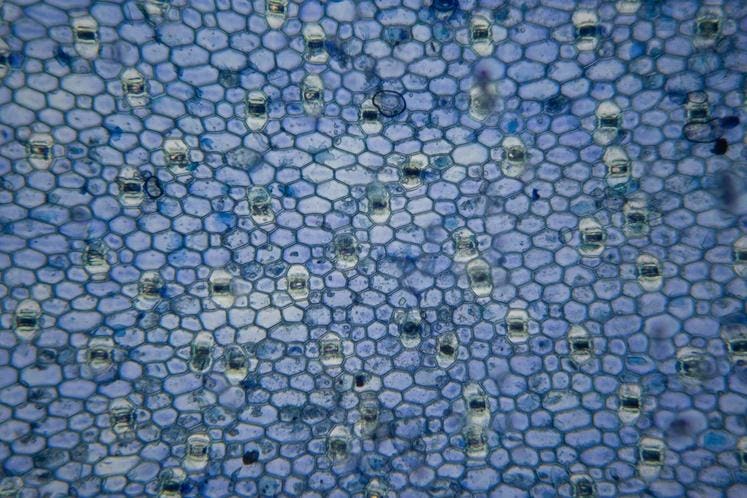

Oxalates are small organic acids, often stored as calcium oxalate crystals, that plants produce to manage calcium and mineral reserves for vital processes such as building new cell walls and stabilizing cell membranes. They also help regulate water balance and deter insects and grazing animals.

In humans, oxalates have earned their anti-nutrient label because they bind calcium and, to a lesser extent, magnesium, iron, and zinc. This reduces absorption in the gut and can contribute to nutrient deficiencies over time in vulnerable individuals. Oxalates also play a role in forming calcium oxalate kidney stones, the most common type of kidney stone worldwide. A high oxalate burden may further promote oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and even joint pain or fatigue in some people.

Not everyone is equally affected. Individuals with a history of kidney stones, inflammatory bowel disease, fat malabsorption syndromes, bariatric surgery, or a depleted gut microbiome that lacks the oxalate-degrading bacterium Oxalobacter formigenes are at higher risk of problems related to oxalate intake. Low dietary calcium intake also makes oxalates more harmful because less calcium is available to bind oxalates in the gut and escort them safely out of the body.

Food preparation makes a big difference. Raw spinach contains roughly 900 to 1,000 milligrams of oxalate per 100 grams, while boiling reduces soluble oxalates by 70 to 80 percent. Controlled lab studies, such as Chai and Liebman in Journal of Food Composition and Analysis (2005), confirm that boiling vegetables like spinach and Swiss chard leaches soluble oxalates into the cooking water, lowering what remains available for absorption. Dehydration has the opposite effect. Kale chips can concentrate oxalates so that a small serving may equal several cups of raw kale. Pairing oxalate-rich vegetables with calcium-rich foods also helps, because the oxalate binds calcium in the gut and is excreted rather than absorbed.

What the Science Says

Human feeding trials support these effects. Brogren and Savage in Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2003) showed that eating spinach with dairy significantly reduced oxalate absorption, measured by urinary oxalate excretion. Larger observational research, including analyses from the long-running Nurses’ Health Study (Harvard, ongoing since 1976), has found only a modest association between dietary oxalate and kidney stone risk, and mainly in those with low calcium intake.

It is also important to note that vegetables high in oxalates, such as spinach, beets, and Swiss chard, are simultaneously among the richest sources of folate, magnesium, vitamin K, nitrates, and phytonutrients that support cardiovascular and bone health. Prospective cohort studies, such as those published in the Journal of the American Heart Association (2020), consistently link higher leafy green intake with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that oxalates can pose problems for at-risk populations, but that preparation strategies such as boiling, pairing with calcium, and dietary diversity allow people to capture the broad health benefits of these vegetables without substantially increasing risk. For most people, the goal should not be to avoid oxalate-rich foods entirely but to prepare them wisely and balance them within a varied diet.

Lectins: Plant Defense Proteins, Human Context Matters

Soaked and cooked red kidney beans

getty

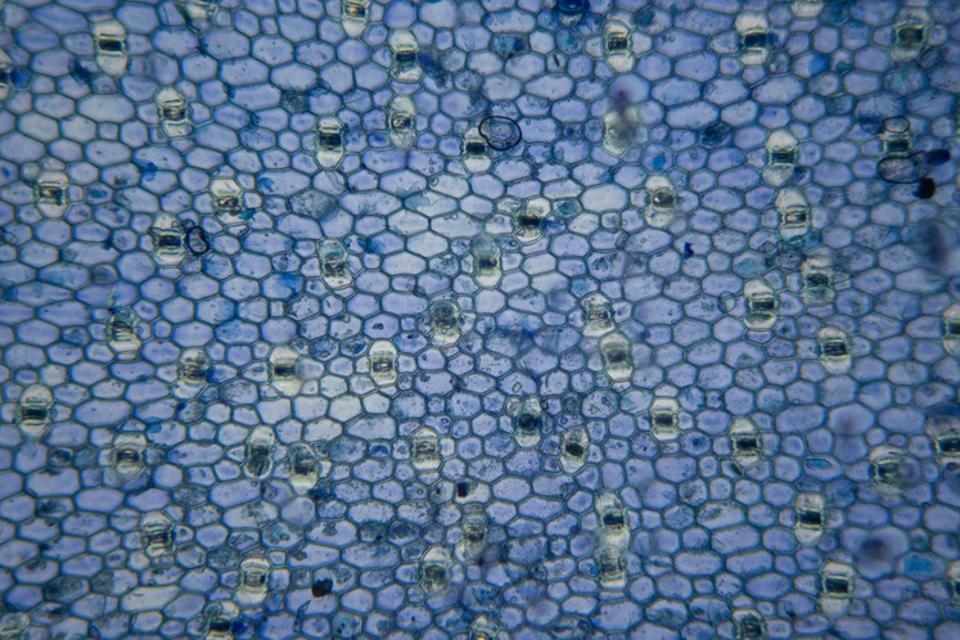

Lectins are carbohydrate-binding proteins that plants produce as part of their natural defense system. By attaching to sugars on the surfaces of microbes and pests, they help protect seeds and leaves from damage. Seeds and legumes are especially high in lectins, since they need to withstand insects and animals that might eat them before germination.

In humans, lectins have earned their reputation as “anti-nutrients” because they can bind to carbohydrates on intestinal cells and immune receptors, which may irritate the gut lining. In raw or undercooked beans, this can cause nausea, diarrhea, or even more serious symptoms. As few as five raw kidney beans can be enough to trigger illness. Heat, however, changes the equation. Proper boiling or pressure cooking destroys more than 99 percent of lectin activity, which is why canned beans are safe and why traditional preparation methods such as soaking, sprouting, and fermenting have been used for centuries.

Sensitivity varies from person to person. Individuals with autoimmune conditions, impaired gut barriers, or low microbiome diversity may be more vulnerable to lectin-related irritation. In these cases, lectins can aggravate the intestinal lining, increasing permeability and triggering low-grade immune activation. This may worsen symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a chronic functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits such as diarrhea, constipation, or both. For the vast majority of people, however, lectins in properly prepared legumes and grains are not only well tolerated but beneficial.

What the Science Says

Public health reports have documented outbreaks of “red kidney bean poisoning” from slow cookers that never reached a full boil, underscoring the importance of preparation (UK Food Standards Agency, 2004). Yet the very same foods, once cooked, consistently show health benefits. Randomized trials, including research in the Journal of Nutrition (2012) and the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2014), demonstrate that diets rich in beans and lentils lower inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and improve cholesterol and blood pressure. The evidence suggests that the problem is not lectins themselves but how they are handled.

Phytates: Mineral Blockers or Antioxidants?

Phytates, also called phytic acid or IP6, naturally occur in seeds, grains, legumes, and nuts, where they act as the plant’s main storage vault for phosphorus and essential minerals, fueling germination and early growth. In human nutrition, their reputation as “anti-nutrients” comes from their ability to bind minerals like iron, zinc, and calcium, reducing absorption in the gut. For populations relying heavily on unprocessed grains, this can contribute to deficiencies. Vegans, vegetarians, and people with marginal mineral intake are particularly at risk.

The same chelation that limits mineral absorption is also the reason phytates act as antioxidants. By binding strongly to iron and other transition metals, phytates prevent these metals from catalyzing Fenton reactions, a process where iron and hydrogen peroxide generate hydroxyl radicals, one of the most damaging forms of oxidative stress. In this way, phytates do not quench free radicals directly like vitamin C does; instead, they block their formation at the source.

This duality explains why phytates can be protective in moderation yet problematic if consumed in excess without dietary diversity. Preparation methods such as soaking, sprouting, fermenting, and traditional sourdough reduce phytate levels enough to improve mineral bioavailability while preserving some of their protective chelation. Striking the right balance, not too much and not too little, is key.

What the Science Says

In a randomized crossover trial published in a Nature publication (2018), patients with type 2 diabetes who received three months of IP6 supplementation showed lower levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and improved HbA1c compared to periods without IP6. Observational studies, including research in the Journal of Renal Nutrition (2016), have also linked higher phytate intake with reduced vascular calcification in patients with kidney disease. These findings suggest that phytates are not just neutral but may play a protective role in metabolic and vascular health.

Goitrogens: Crucifers and Thyroid Balance

Goitrogens are naturally occurring compounds found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, and cauliflower. For the plant, these compounds, part of a broader family called glucosinolates, act as chemical defenses against pests and pathogens. When a plant is chewed or damaged, glucosinolates break down into active byproducts that discourage insects and microbes.

In humans, the same chemistry can sometimes interfere with iodine uptake in the thyroid gland, which may impair thyroid hormone production. This is mainly a concern for people who already have low iodine intake or existing thyroid disease. Most people, however, can enjoy cruciferous vegetables freely, and the benefits usually far outweigh any theoretical risk.

The mechanism is straightforward: goitrogens compete with iodine for transport into the thyroid. If iodine intake is sufficient, the effect is minimal, but when iodine is scarce, this competition can reduce thyroid hormone synthesis. Cooking changes the equation as well. Steaming or boiling crucifers reduces goitrogenic activity by 50 to 70 percent, making them even less likely to disrupt thyroid function.

What the Science Says

Epidemiologic studies consistently show that diets rich in cruciferous vegetables are linked with lower cancer risk and better cardiovascular outcomes. Research in the International Journal of Food Science (2022) confirmed that common cooking methods substantially reduce goitrogen levels. Clinical evidence suggests that only those with low iodine intake or thyroid dysfunction are at risk for problems. For the vast majority, cruciferous vegetables remain a cornerstone of a healthy diet.

Tannins, Saponins, and Alkaloids: The Lesser-Known Players

Red wine and dark chocolate.

getty

Tannins, saponins, and alkaloids are a diverse group of plant compounds that serve as natural defense systems. Tannins, the bitter and astringent molecules in tea, wine, cocoa, and many fruits, help deter herbivores and pathogens. Saponins, which create a soapy froth when legumes or quinoa are soaked, discourage insects and fungi. Alkaloids, including the nightshade family compounds in tomatoes, potatoes, and eggplants, often act as chemical shields against predators.

For humans, these compounds have a mixed reputation. Tannins can bind iron, potentially lowering absorption and contributing to anemia in those with marginal iron intake. Saponins may irritate the gut in high amounts. Alkaloids have been blamed anecdotally for joint pain or inflammation in sensitive individuals, though strong evidence is limited. These features are what earn them the “anti-nutrient” label.

Yet much like oxalates, phytates and lectins, the full story is more nuanced. Tannins are also potent polyphenols with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Large population studies, including data published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2002), have not found any consistent link between tea or cocoa consumption and iron deficiency anemia. Saponins, beyond their gut effects, may lower cholesterol by binding bile acids and altering lipid metabolism (Journal of Functional Foods, 2016). Alkaloids, while potentially irritating in excess, also contribute antioxidants such as lycopene in tomatoes and solanidine derivatives in potatoes, which have been studied for possible anticancer activity.

What the Science Says

Human studies generally show that the negative effects of tannins and saponins are context-dependent. Iron absorption can be inhibited when tea is consumed with iron-rich meals, but the effect is offset by vitamin C or by consuming tea between meals. Randomized trials have demonstrated cholesterol-lowering effects of saponins, particularly from legumes and quinoa (Journal of Functional Foods, 2016). For alkaloids, strong clinical data linking nightshade vegetables to joint pain are lacking. Instead, diets high in tomatoes and peppers are consistently associated with reduced cardiovascular and cancer risk. Overall, these compounds appear to be beneficial in most dietary contexts, with problems arising mainly in sensitive individuals or when intake is extreme.

Common Misconceptions About Anti-Nutrients

- MYTH: “All foods with anti-nutrients are harmful.”

- FACT: In reality, many have protective and antioxidant roles.

- MYTH: “Lectins must be avoided.”

- FACT: Properly cooked beans and lentils are safe and anti-inflammatory.

- MYTH: “Spinach and Kale are bad because of oxalates.”

- FACT: Dehydrated ‘chip’ versions can carry very high levels, but other means of cooking and calcium pairing typically mitigate the risks.

- MYTH: “Everyone should avoid anti-nutrients.”

- FACT: Only certain individuals with health conditions need restrictions.

What You Can Actually Test (and What Not to Waste Money On)

If someone reports symptoms they link to “anti-nutrients,” the work-up starts with clinical basics: a food and symptom diary and a short, structured elimination and re-challenge. Then targeted labs are used, tied to the suspected compound, rather than broad unfocused panels. For oxalates, the evidence-based workup is a 24-hour urine stone risk profile that includes calcium, oxalate, citrate, uric acid, sodium, sulfate, creatinine, urea, and total volume, plus stone analysis if available. This is considered standard practice in evaluation of nephrolithiasis and helps uncover diet-related risk and malabsorption states that drive oxalate load.

In select or severe cases such as recurrent stones at a young age, nephrocalcinosis, or a strong family history, genetic testing for primary hyperoxaluria involving AGXT, GRHPR, and HOGA1 can be appropriate. These conditions are rare but important to identify because dietary advice and therapeutic strategies differ. Stool metagenomics or targeted PCR can quantify Oxalobacter formigenes, the oxalate-degrading bacterium, and may correlate with urinary oxalate. Clinical utility is still evolving and not yet guideline standard, but proof-of-concept colonization studies have shown reductions in urinary oxalate with variable responses.

For goitrogens in people with thyroid disease or low iodine intake, thyroid function testing with TSH and free T4 is essential. Urinary iodine concentration, measured either in a spot sample or a 24-hour collection, provides additional insight into iodine status. This combination helps identify individuals in whom high crucifer intake could exacerbate thyroid dysfunction.

For phytates and tannins, which can impair mineral absorption, iron status can be assessed using hemoglobin, ferritin, and transferrin saturation. If low, adjustments in food preparation and timing, such as adding vitamin C to meals or consuming tea and coffee away from iron-rich foods, are usually more effective than avoidance.

For lectins, there is no validated blood test for “lectin sensitivity.” IgG “food sensitivity” panels should be avoided because they reflect exposure and tolerance, not pathology. Major allergy and immunology societies explicitly advise against their use. Diagnosis in suspected cases relies on history and a structured elimination and re-challenge.

Microbiome sequencing, methylation profiling, and biological age tests may be interesting but they are not clinically endorsed for determining whether someone should exclude anti-nutrient containing foods. At present, they are best reserved for research or long-term wellness tracking rather than clinical decision-making.

Hard no’s: skip IgG food sensitivity panels. They do not diagnose disease. If proof is needed, use a tight elimination and re-challenge and pair it with condition-specific labs such as a 24-hour urine for oxalate risk or thyroid testing for goitrogen concerns.

How to Reduce the Impact of Anti-Nutrients

Traditional preparation techniques can dramatically lower levels of anti-nutrients. Soaking, sprouting, and fermentation are preferred methods as they are effective at removing toxic compounds yet preserve nutritional value. Although many studies have shown the effectiveness of boiling on removal of anti-nutrients, boiling is not preferred in most cases as it leaches out water soluble vitamins and minerals like folate, potassium, B vitamins, and vitamin C. It is also less effective against phytates that are heat stable. One exception is lectins that typically require boiling or pressure cooking for consistent removal. Steaming and microwaving can better preserve nutrients but are less potent against stubborn anti-nutrients like phytates. Dehydration and baking can actually concentrate certain anti-nutrients and should be avoided if this is the goal of food preparation.

- Soaking legumes and some vegetables in water overnight allows many water-soluble anti-nutrients to leach out, particularly those concentrated in skins. This can lower phytate, tannins, calcium oxalate, and some lectins though the effect varies by plant.

- Sprouting (germination) goes a step further by activating enzymes that break down anti-nutrients. Over a few days, sprouting can reduce phytate content by up to 80 percent and slightly lower lectins while increasing nutrient availability.

- Fermentation, an ancient method still widely used today, powerfully degrades phytates and lectins. Sourdough fermentation, for example, breaks down more anti-nutrients in grains than conventional yeast, improving mineral absorption. Fermenting pre-soaked legumes can reduce phytate by nearly 90 percent.

- Boiling, is the most consistent way to remove or deactivate lectins, but it can leach out many water-soluble nutrients and degrade heat-sensitive vitamins limiting its broader utility.

Combining methods yields the greatest effect. For example, soaking, sprouting, and lactic acid fermentation together can lower phytate in quinoa by 98 percent. Using multiple traditional methods improves digestibility and nutrient absorption while preserving the nutritional value of plant foods.

The Bottom Line

Lunch bowl with pearl barley, red beans, broccoli and butternut squash

getty

Anti-nutrients are not a reason to avoid vegetables. They are natural compounds that, under certain circumstances, can interfere with digestion or nutrient absorption, and in some people may contribute to kidney stone formation, gastrointestinal discomfort, or exacerbate certain health conditions. However, for the vast majority, their protective effects far outweigh any potential downsides. With thoughtful preparation, dietary variety, and individual adjustments, vegetables remain among the most powerful tools for supporting metabolic, cardiovascular, and overall long-term health.