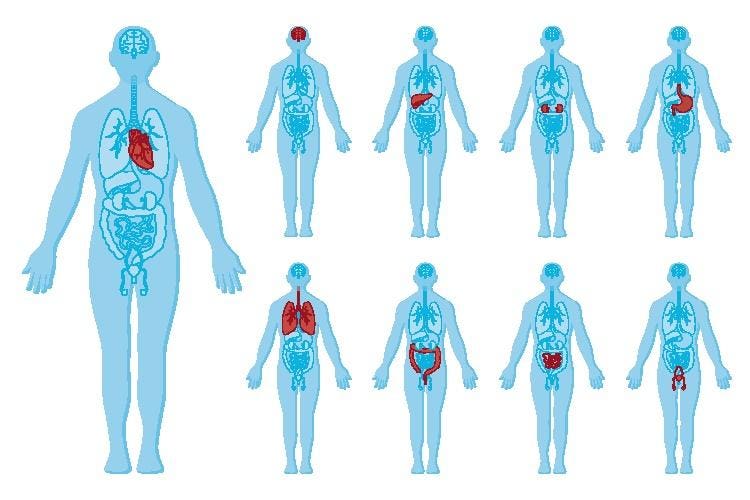

Illustration of a human body anatomy and internal organs. Each figure drawing is on a different layer.

getty

It’s probably not so much that pathologies themselves have changed that much during the last few hundred years of human evolution – it’s that our ability to measure them has exploded with AI.

Take this from the Modern Pathology journal of the College of American Pathologists:

“The availability of enormous volumes of digital health care data, developments in computer power, and advancements in ML techniques along with the creation of deep neural network methods have further thrust AI-ML into the forefront of medical research and practice in the 21st century. In pathology and medicine today, AI-ML is being increasingly used to enhance diagnostic precision, expedite clinical workflows, customize patient care, and enhance the overall patient experience.”

So, we know a lot more now that we can use AI to evaluate how cellular pathologies work.

One thing that we’ve learned is that viruses and other pathologies can be insidious players, which some might call “body hackers” – living unseen in the human body over time, and even influencing mitochondrial development or gene expression.

Viruses are Parasites

In a recent Ted talk, Amy Proal, CEO of the PolyBio Research Foundation, clued us in on how to spot this kind of sinister development.

“These chronic pathogens are the closest thing there are to hackers of the human body,” she said. “As they live in us, they can create proteins and products that actively distort the signaling of our own human genes. In fact, pathogens can drive every feature of human aging.”

She noted the work of herpes simplex and toxoplasma in the body, and even documented some research on Sars-Covid virus, which can remain in the body for years as “long covid,” with or without symptoms.

The Parasite at Work

“Pathogens hijack host cell metabolism, or the ability of our cells to correctly produce energy, and by doing that, they can directly drive the mitochondrial dysfunction that accompanies aging,” Proal explained. “Once in us, they act purely for their own benefit, draining our function to bolster their own. In fact, all viruses are intracellular parasites, and what that means is: they’re not even alive, so they can’t create their own energy or replicate and create a new copy of themselves, without stealing from the cells that they infect.”

Proal explained how it works:

“(The pathogens) pull the raw materials they need to function directly out of our own mitochondria, which inevitably dysregulates and reprograms the metabolism of the infected human cell,” she said.

Science to the Rescue

In another part of the lecture, Proal showed off some diagrams by which humans could presumably use AI data to come up with very detailed pictures of what is at work inside our bodies, in different microbiomes. That, she suggested, sets the stage for further intervention.

“What do we do about this pathogen-driven age distortion?” she asked. “Well, first, we need to take it seriously.”

Noting advances in things like cellular reprogramming, or CRISPR gene editing, she pondered whether these strategies will work without reining in pathogen activity.

“I just don’t know how well those interventions are truly going to work,” she said, “if you have a persistent virus or parasite slowly crawling up your nerves and into your brain over time, distorting the system. It’s like trying to put out a forest fire when someone is still putting fuel on the flames. We don’t need to begin editing our human gene until we first take logical steps to curb the activity of the pathogens that can hack them in the first place.”

It’s a compelling argument: that to really advance healthcare, we’ll have to track and deal with all of those little creepy crawlies that avoided detection until just a few years ago with the rise of large language models.

“There are dozens of existing … medications and compounds that we can integrate into healthspan- extending protocols, and many new anti-pathogen compounds or immune-activating therapies we can work to create,” she pointed out.

The Old Ways Persist

One big obstacle that Proal mentioned is the old-fashioned ways that medicine still works, in the era of ChatGPT.

“Right now, if you walk into a doctor’s office, the testing they can do to identify persistent pathogens in your body are often inaccurate and out of date,” she noted.

That, she suggested, can change fast.

“There are teams across the world with new diagnostic platforms that can be iterated into the chronic infection space,” Proal said, in conclusion. “For example, there are now groups that can take your blood, and identify small vesicles in the blood carrying tiny amounts of a pathogen or its proteins that are totally missed by current standard testing. We must invest in these new diagnostic test platforms so that they can be added into biological age tracking. So that’s it. Let’s do it. Let’s add the activity of persistent pathogens into our aging models. Because if we can better diagnose, track and curb the activity of the pathogen hackers in our bodies, then we will actually succeed in extending healthspan.”

It’s compelling, for a number of reasons. It’s not hard to imagine how lurking Sars-cov-2 or herpes simplex or anything else can “hack” our bodies at genetic and cellular levels. And the interventions make sense. So we can assume that a lot of this will develop in the clinical communities in 2026 and beyond.