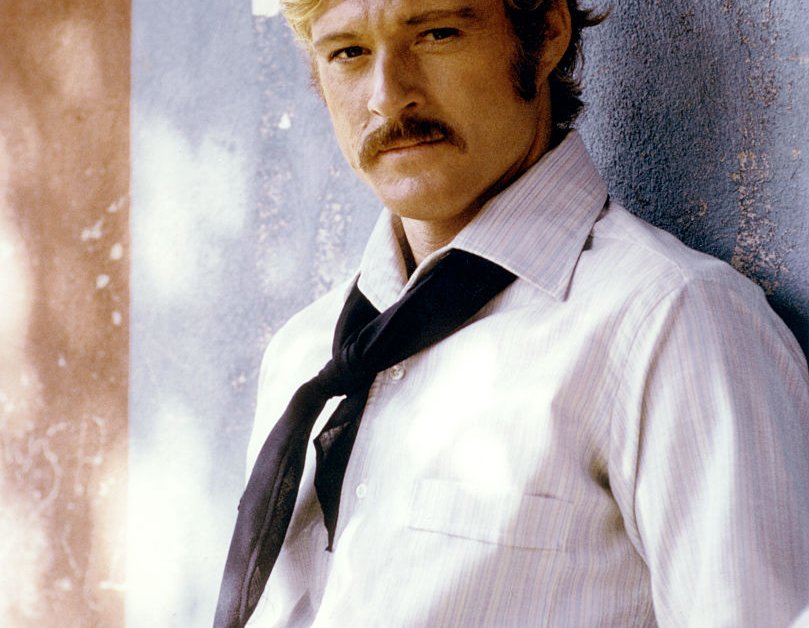

A genuinely dazzling movie star who used his charm, influence, and money to give aspiring filmmakers a leg up in the movie business, to help protect the natural world from those who would strip it bare for their own gain, to show by example how film storytelling can not only reflect facets of the American character but help shape it: a human being who could do all that seems almost impossible to fathom in this age of disinformation, misinformation, and ugly political discord. But that was Robert Redford, who died on September 16 at age 89. Redford was an actor, a producer, a director; over the course of his long career, he touched every aspect of the movie business. But most essentially, he was a communicator, an artist who could speak to us in a place beyond words, with just the flicker of a smile—though even then, as a performer and as a person, he was the kind of guy who made you instinctively lean in close, to want to hear what he had to say. Redford could do it all, such that he seems to have packed more than one lifetime into his 89 years on Earth.

Redford contracted polio as a child growing up in Los Angeles, in the days before vaccines. Though his case wasn’t severe enough to land him in an iron lung, he did have to spend weeks in bed recuperating, and as a reward, his mother took him to Yosemite National Park. When I interviewed Redford in 2018, he told me about that trip, about how the family car emerged from a tunnel, revealing the park in all its natural splendor. “All the magical beauty of that that area—it looks like it was sculpted by God,” he said. Later, as a teenager, he worked at Yosemite for three summers, though he was hardly a model kid. He hung out with a rough-around-the-edges crowd of kids in high school, and reportedly sat in the back of the auditorium at his graduation, reading Mad magazine.

Read more: How One of Robert Redford’s Landmark Films Nearly Fell Apart

His hope was to become a painter, and by age 19 he’d saved up enough money to spend a year in Europe, “on the bum,” as he put it. Though he would continue to paint and draw throughout his life, that trip was formative for him in other ways: he understood more about politics, about nature, about how people elsewhere in the world thought and lived. He studied art—showing an interest in animation, specifically—at the University of Colorado at Boulder, though by the late 1950s, he’d found his way to acting. His career began in television and on stage: his breakthrough came in Neil Simon’s 1963 play Barefoot in the Park—later he would also costar, with Jane Fonda, in the 1967 film version.

From there, you’d need a scroll a million words long to adequately list Redford’s accomplishments. His directorial debut, 1980’s Ordinary People, won four Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director. As director, he would go on to adapt Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It (1992), and he assayed the quiz show scandal of the 1950s with Quiz Show (1994). And as an actor, Redford chose his projects carefully, often gravitating to roles that somehow connected with the absurdity of American politics, and its potential to foster corruption. Those films included Michael Ritchie’s 1972 satire The Candidate and also, of course, Alan J. Pakula’s glorious true-to-life journalism drama All the President’s Men, from 1976, in which he played reporter Bob Woodward who, along with Carl Bernstein (played in the film by Dustin Hoffman) broke the Watergate scandal. Redford’s career seemed to be shaped around the idea that the best qualities of the American spirit—maybe best defined as a kind of forthright, unassuming honesty—could prevail against corruption and deceit. And he wasn’t content to stop at being an actor, producer, and director: he also founded the Sundance Institute, established in 1981 to help independent filmmakers bring their work to a wider audience. In 1985, he expanded Sundance’s reach by taking over what was then called the United States Film and Video Festival, and the Sundance Film Festival was born.

All of these are clearly fantastic, laudable accomplishments—yet a laundry list of all the things Redford accomplished in his lifetime isn’t really the best way to honor his gifts. To watch Redford in a movie—whether it’s The Sting, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, or the one-man vehicle All Is Lost, in which he gave perhaps the greatest of his late performances—is to find yourself yielding to an irresistible magnetic power. Sydney Pollack’s 1973 The Way We Were was a movie about political ideals, rooted in the history of McCarthyism and the Hollywood Blacklist. Sure it was—but little girls, and big ones too, who saw it in 1973 found themselves wrapped in its swoonworthy cocoon of romance. That’s not a negligible thing, it’s an important one, especially when we’re talking about all the blessings actors can give us. The way Redford’s Hubbell Gardiner looks at his long-lost lover, Katie Morosky (played by Barbra Streisand), during a chance reunion on a New York City street is a symphony of adult regret and longing, an acknowledgement that making the right choice always takes something from us. It’s a look that says, mournfully, “You can’t have everything”—not even in the movies, the place we have so often gone, over the past 100 years or so, to see our own reflection. Redford’s face could tell nothing but the truth.

That was true outside of the movies, too. During our interview, Redford spoke of the necessity of standing up to those in power who seem bent only on destruction—not just of the environment, but of the very values that we messy, flawed citizens cling to. We try to be generous when it’s easier to be selfish, to preserve when it’s easier to destroy and consume. “I think you have to maintain hope, because that’s the only life raft you’ve got,” he told me. “Right now, I think hope is more needed than ever, because things seem so hopeless. And if you allow yourself to sink into that feeling, then you’re part of the problem.” He couldn’t have put it more simply. And now that he’s gone, the words really stick.