She wasn’t elected and she doesn’t cast votes. But over the past week, Elizabeth MacDonough, the quietly powerful Senate parliamentarian, may have had more influence over Donald Trump’s legislative agenda than anyone else in Washington.

After meeting with Republicans and Democrats behind closed doors, MacDonough in recent days has significantly shrunk the size of the President’s sweeping tax-and-spending package known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill” by striking several measures that violated an arcane, decades-old Senate rule known as the Byrd Rule, which prohibits provisions considered “extraneous” to the federal budget in the kind of legislation Republicans are trying to craft.

One of the main GOP provisions the parliamentarian said did not satisfy the Byrd Rule was a measure to push some of the costs of federal food aid onto states, sending Republicans back to the drawing board to find the billions in savings that provision would have yielded. MacDonough also rejected measures to bar non-citizens from receiving SNAP benefits and one that would have made it more difficult to enforce contempt findings against the Trump Administration. MacDonough could issue additional guidance this week.

The spate of rulings from the Senate parliamentarian, an official appointed by the chamber’s leaders to enforce its rules and precedents, has significantly complicated the prospects of passing Trump’s tax and spending bill by the July 4 deadline he imposed on Congress. Republicans have been scrambling for months to secure enough votes for Trump’s megabill, which centers on extending his 2017 tax cuts and delivering on several of his campaign promises, such as boosting border security spending and eliminating taxes on tips. Support for the package has softened this month as more Republicans warn that it would add trillions of dollars to the deficit without further spending cuts.

But the parliamentarian’s latest rulings will force Republicans to either strip those provisions from the bill or secure a 60-vote supermajority to keep them in, a nearly impossible hurdle given that Senate Republicans only hold 53 seats. MacDonough ruled that some of the provisions have little business in a budget reconciliation bill, which can make big changes to how the federal government spends money but, under Senate rules, isn’t allowed to substantively change policy.

MacDonough’s rulings came about after days of behind-the-scenes meetings between her office and Senate staff. They illustrate the often-overlooked power of Senate procedure—and the person tasked with interpreting it. MacDonough, a former Justice Department trial attorney and the first woman to ever serve as Senate parliamentarian, is Washington’s ultimate rules enforcer. She was appointed in 2012 and has struck prohibited measures from reconciliation bills several times under both Republicans and Democrats.

Now, the parliamentarian’s rulings may force Republicans back to the drawing board just as they were hoping to finalize their legislative centerpiece.

Here’s what to know about the rejected measures.

What is the Byrd Rule?

The Byrd Rule, adopted in 1985, is a procedural constraint named after the late Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia to prohibit “extraneous” provisions from being tacked onto reconciliation bills, which are fast-tracked budget packages that allow legislation to pass with a simple majority, bypassing the 60-vote filibuster threshold.

The rule makes it so that every line of a reconciliation package must have a direct and substantive impact on federal spending or revenues. Provisions that serve primarily policy goals—rather than budgetary ones—are subject to elimination by a parliamentary maneuver known as a point of order. Whether a point of order is sustained is ultimately made by the parliamentarian, who is essentially the Senate’s umpire tasked with providing nonpartisan advice and ensuring that lawmakers are complying with the Senate’s rules.

Parliamentarians often face backlash during the budget reconciliation process, when they determine whether policy proposals comply with the constraints of the Byrd Rule.

What’s been cut so far?

MacDonough’s rulings have invalidated a number of headline-grabbing GOP provisions, including a plan requiring states to pay a portion of food benefits—the largest spending cut for SNAP in the bill.

The SNAP measure, which the parliamentarian said violated the Byrd Rule, would have required all states to pay a percentage of SNAP benefit costs, with their share increasing if they reported a higher rate of errors in underpaying or overpaying recipients. Some lawmakers warned their states would not be able to make up the difference on food aid, which has long been provided by the federal government, and could force many to lose access to SNAP benefits.

Republican Sen. John Boozman of Arkansas, the chairman of the Agriculture Committee, said in a statement that he’s looking for other ways to cut food assistance without violating Senate rules.

Another rejected provision would have zeroed out $6.4 billion in funding of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, effectively shuttering the agency. The bureau was created by Democrats as part of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act in the aftermath of the financial crisis as a way to protect Americans from financial fraud. Republicans have long decried the CFPB as an example of government over-regulation and overreach. “Democrats fought back, and we will keep fighting back against this ugly bill,” said Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who said the GOP plan would have left Americans vulnerable to predatory lenders and corporate fraud.

The Senate parliamentarian also blocked a GOP provision intended to limit courts’ ability to hold Trump officials in contempt by requiring plaintiffs to post potentially enormous bonds when asking courts to issue preliminary injunctions or imposing temporary restraining orders against the federal government.

Democrats hailed that decision by the parliamentarian, noting that it would have severely undermined the judiciary’s ability to check executive overreach. Senate Democrats “successfully fought for rule of law and struck out this reckless and downright un-American provision,” Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer said in a statement.

MacDonough also nixed provisions to reduce pay for certain Federal Reserve staff, slash $293 million from the Treasury Department’s Office of Financial Research, and dissolve the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which is tasked with overseeing audits of publicly traded companies. Each of these proposals, she ruled, either lacked sufficient budgetary impact or were primarily aimed at changing policy, not federal revenues or outlays.

MacDonough also rejected language in the bill drafted by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee that would have exempted certain infrastructure projects from judicial review under the National Environmental Policy Act. The rejected proposal would have allowed companies to pay a fee in exchange for expedited permitting, a move Republicans argued would streamline bureaucratic delays.

Also disqualified was a measure to repeal the Biden Administration’s tailpipe emissions rule for cars and trucks manufactured after 2027. MacDonough ruled that the environmental provisions were either insufficiently tied to federal spending or failed to meet the Byrd Rule’s strict thresholds for inclusion.

Are the parliamentarian’s rulings final, or could they be overturned?

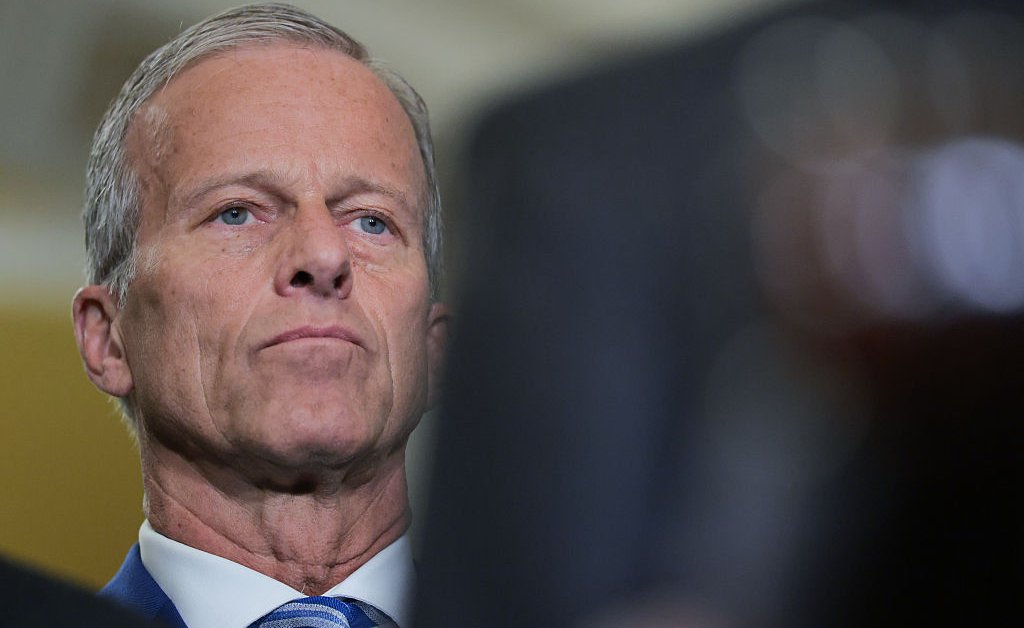

The parliamentarian’s decisions could, in theory, be overturned. Senate Majority Leader John Thune of South Dakota has the authority to ignore her ruling by calling for a floor vote to establish a new precedent—essentially overruling the Senate’s referee.

Parliamentarians have been ignored in the past, though it is quite rare. In 1975, Vice President Nelson Rockefeller ignored the parliamentarian’s advice as the Senate debated filibuster rules. MacDonough has been overruled twice before: in 2013, when Democrats eliminated filibusters to approve presidential nominees, and in 2017, when Republicans expanded the filibuster ban to include Supreme Court nominations.

But Thune has signaled he has no intention of going down that path this time. “We’re not going there,” the Senate Majority Leader said on June 2 when asked by reporters about overruling MacDonough.

Thune could also fire the Senate Parliamentarian and replace her with one willing to interpret the rules more in line with how Senate Republicans view them.