It’s not just you — internet outages severe enough to disrupt everyday services for many people have become more frequent and wide-ranging, experts say.

When internet services company Cloudflare crashed Tuesday — prompting significant, hourslong disruptions at companies ranging from X to OpenAI to Discord — it was the third major internet outage in the space of about a month.

While there’s plenty of finger-pointing to go around, two things are clear: Popular consumer businesses increasingly rely on a handful of giant companies that run things more cheaply in the cloud, and when one of those companies isn’t extraordinarily careful, an obscure software vulnerability or tiny mistake can reverberate through to many of their customers, making it seem like half the internet has been unplugged.

“This spate of outages has been uniquely terrible,” said Erie Meyer, the former chief technical officer of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau under the Biden administration. “It’s like what we were told Y2K would be like, and it’s happening more often.”

It’s become a common enough occurrence that jokes about the failures, rooted in an understanding of the basics of internet infrastructure, have become popular memes in the computer science world.

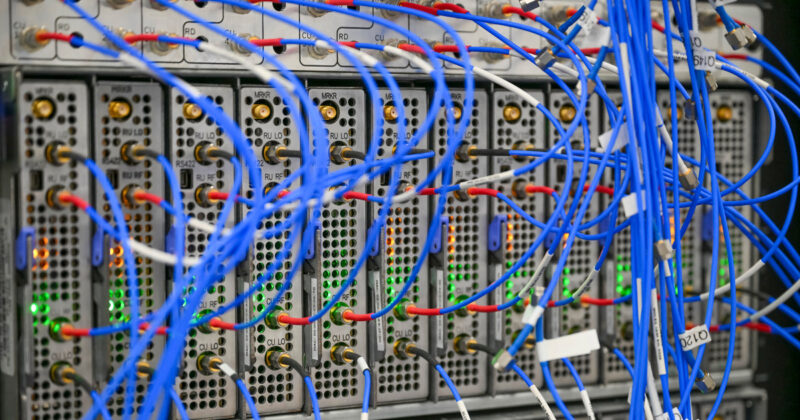

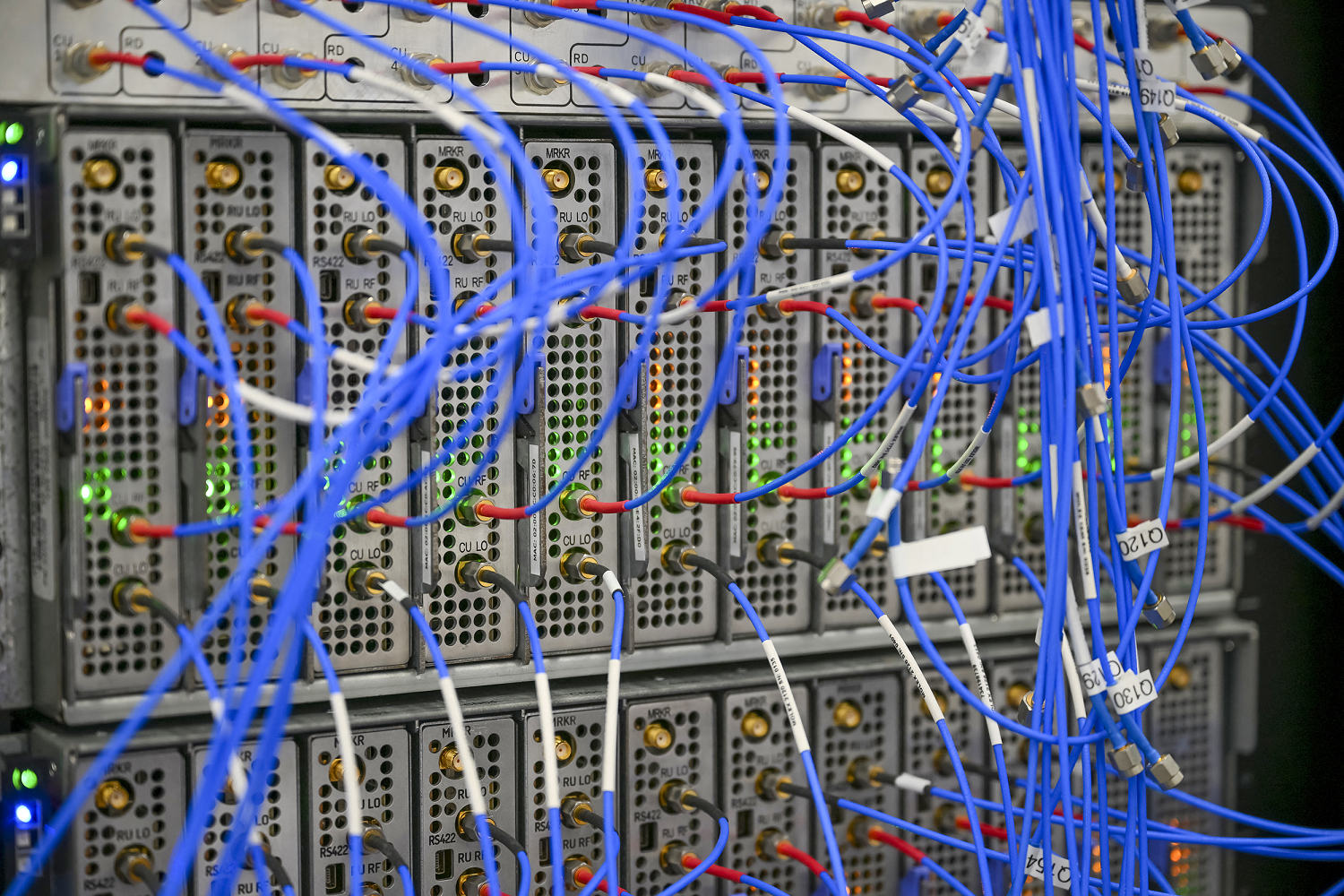

Major cloud companies are often referred to as hyperscalers, meaning once they have established a viable business, it can be relatively straightforward to rapidly build out their infrastructure and offer those services at competitive prices. That has resulted in a handful of companies dominating the industry, which critics note creates single points of failure when something goes wrong.

“When one company’s bug can derail everyday life, that’s not just a technical issue, that’s consolidation,” Meyer said.

Outages are as old as the internet. But since late October there have been three major ones — an unprecedented number for such a short span of time — that caused serious problems for wide swaths of people.

The first was Amazon Web Services on Oct. 20, taking with it many people’s access to everything from gaming platforms Roblox and Fortnite to Ring cameras. It reportedly kept some from being able to operate their internet-connected smart beds.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., a long-standing critic of the tech industry, wrote on X after the AWS outage that it was a reason “to break up Big Tech.”

“If a company can break the entire internet, they are too big. Period,” she said.

Microsoft’s cloud computing platform, Azure, went down on Oct. 29, rendering a host of the company’s services inoperable around the globe just before its quarterly report. Those two outages each caused major headaches for at least two airlines, preventing passengers from checking in online: Delta, which uses AWS, and Alaska, which uses Azure.

Then came Cloudflare’s disruption Tuesday, which CEO Matthew Prince said was the company’s worst since 2019.

“We are sorry for the impact to our customers and to the Internet in general,” he wrote in a technical explanation after the outage.

“Given Cloudflare’s importance in the Internet ecosystem any outage of any of our systems is unacceptable,” he added. “That there was a period of time where our network was not able to route traffic is deeply painful to every member of our team. We know we let you down today.”

The three companies each dealt with different issues. Cloudflare initially thought it was under a massive cyberattack, but then traced the issue to a “bug” in its software to combat bots. AWS and Microsoft each had different issues configuring their services with the Domain Name System, or DNS, the notoriously finicky “phonebook” for the internet that connects website URLs with their technical, numerical addresses.

Those issues come a year after a particularly unusual case, in which companies around the world that used both Microsoft-based computers and the popular cybersecurity service CrowdStrike suddenly saw their systems crash and display the “blue screen of death.” The culprit was a glitch in what should have been a routine CrowdStrike automatic software update, leading to flight delays and medical and police networks going down for hours.

Ultimately, each was an instance of a minor software glitch that rippled across those companies’ enormous systems, crashing website after website.

Asad Ramzanali, the director of artificial intelligence and technology policy at Vanderbilt Policy Accelerator, as well as the former deputy director for strategy at the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy under the Biden administration, called the tendency for giant companies to experience such wide-ranging outages a national risk.

“This concentration is both a market failure and a national security risk when we have so much of society dependent on these layers of infrastructure,” he told NBC News.

James Kretchmar, the chief technology officer of Akamai’s Cloud Technology Group — another cloud services giant — said that it is always possible for a cloud company’s engineers to reduce outages’ likelihood and severity, but that companies need to use them strategically.

“You don’t have infinite nerds. But it’s not like this is something where you would have to throw your hands up and say, ‘There’s just no way,’” he said.

There’s also some growing push for these outages to be treated as more than minor nuisances or the cost of doing business in the digital age.

J.B. Branch, the Big Tech accountability advocate at Public Citizen, a progressive nonprofit that advocates for public interests, called for more government regulation of the cloud industry.

“There needs to be investigations whenever these outages happen, because whether we like it or not, the entire infrastructure that our economy is kind of running on, digitally at least, is owned by a handful of companies, and that’s incredibly concerning,” he said.