Artificial light is a part of night-time city life, but new research shows that its excessive use is causing problems

Light pollution is a growing issue for our cities, and Hong Kong is no exception (photo taken on … More

How dark is the night sky where you live? If you’re in an urban area, the answer will likely be “not dark at all”. The pervasiveness of artificial light – be it in the form of streetlamps, billboards, screens or floodlights – keeps our cities bright long after most people have gone to bed. And it’s on the rise.

In 2016, a group of researchers found that 83% of the world’s population and more than 99% of people in the U.S. and Europe live under light-polluted skies. In 2023, some of the same authors showed that the average night sky is getting brighter by 9.6% per year, due to artificial light in our surroundings spilling into the atmosphere. This is equivalent to a quadrupling of sky brightness over the duration of a human childhood (18 years).

And while it’s true that almost all light pollution is generated in urban areas, its effects extend beyond the streetscape. The ‘light domes’ of Las Vegas and Los Angeles can be seen from Death Valley National Park, despite it being 150km and 250km away, respectively. For many city-dwellers, true outdoor darkness is not something they experience regularly.

In discussions around light pollution, the switch to LED (light-emitting diodes) streetlamps is often mentioned as a contributing factor. The high efficiency and low cost of LEDs makes them increasingly common on our urban roads. But if its pollution we’re interested in, then it’s not the streetlamps we should be talking about.

The Nachtlichter (“night lights” in German) campaign involved hundreds of citizen scientists … More

Bright lights, big city

In Germany in 2021, a group of 257 citizen scientists, led by Dr Christopher Kyba (Ruhr University Bochum), carried out a novel study on artificial light at night (ALAN). Using a dedicated app called Nachtlichter (“night lights” in German), they counted and classified 234,044 illuminated light sources across a 22-km2 area that included city centers, residential neighborhoods, commercial and industrial areas. No areas with skyscrapers were included in the survey.

Their findings, published last week in the journal Nature Cities, showed that public streetlamps make up a relatively small percentage (10-13%) of all contaminating light sources counted. In dense areas, streetlamps were outnumbered by other light sources by a factor of up to 7.

Instead, they found that private windows were by far the most frequently observed light source, representing more than 48% of the total. Commercial windows were the third most common type of night-time light source (7.4%), with floodlights and other building-mounted lights following closely behind (7.3% of the total). Signs – both illuminated and self-luminous – represented 5.5% of the total count.

In terms of the brightness of surveyed lights, the vast majority of streetlamps were shieled, meaning that the light was being directed towards the ground, rather than ‘trespassing’ into the atmosphere. In contrast, the majority (58%) of observed floodlights and 29% of building-mounted lights were unshielded, and so were casting their light upwards, adding to the overall light pollution.

The team’s study area was chosen specifically to overlap with the path of a passing satellite carrying an instrument called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). VIIRS is ultra-sensitive in low-light conditions, and is regularly used to monitor night-time lights from space. This allowed the Nachtlichter team to make a comparison between their ground-based lighting inventory, and the orbit-based measurements of the same area.

“By comparing these data with the satellite observations, we identified a correlation between the number of counted lights per square kilometer and the radiance observed by the satellite sensor,” says Kyba.

He continues, “Both energy and lighting policy as well as research on the effects of artificial light on the environment have generally focused on street lighting. Our findings indicate that a broader approach that considers all lighting is necessary in order to understand and reduce the environmental impacts of light in cities.”

This photograph taken on March 22, 2025, shows a view of the ancient Acropolis with lights off … More

Going Dark

Another urban sky brightening study published this month focused on Hong Kong; one of the most densely populated regions in the world. There, a group of scientists took advantage of an annual event called Earth Hour to study light pollution.

Organized by the World-Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) to raise environmental awareness, Earth Hour involves the voluntary switching off of lights for one hour (20:30-21:30 local time) on a specified day. The campaign is widely supported in Hong Kong, with more than 4,000 organizations and buildings opting in to the “lights-out” event each year. This provided the team of researchers, led by Dr Chu-Wing So, with an opportunity to directly quantify the impact that bright lights have on the night sky.

They examined footage from an all-sky camera installed on the roof of the Hong Kong Space Museum in the Tsim Sha Tsui district, and collected data from a night sky brightness meter co-located with the camera. This allowed them to compare images of the sky before, during, and after the lights-out hour every year from 2015 to 2024. To look at the influence of street-level billboards on storefronts and illuminated signs closer to the ground, they also carried out wide-field photography and a street-level survey. Taken together, this data showed a night sky that was more than 50% darker on average during the lights-out period. They showed that the presence of clouds also amplified the brightening effect of light pollution – as cloud coverage increased from 40% to 85%, urban night sky brightness increased sixfold.

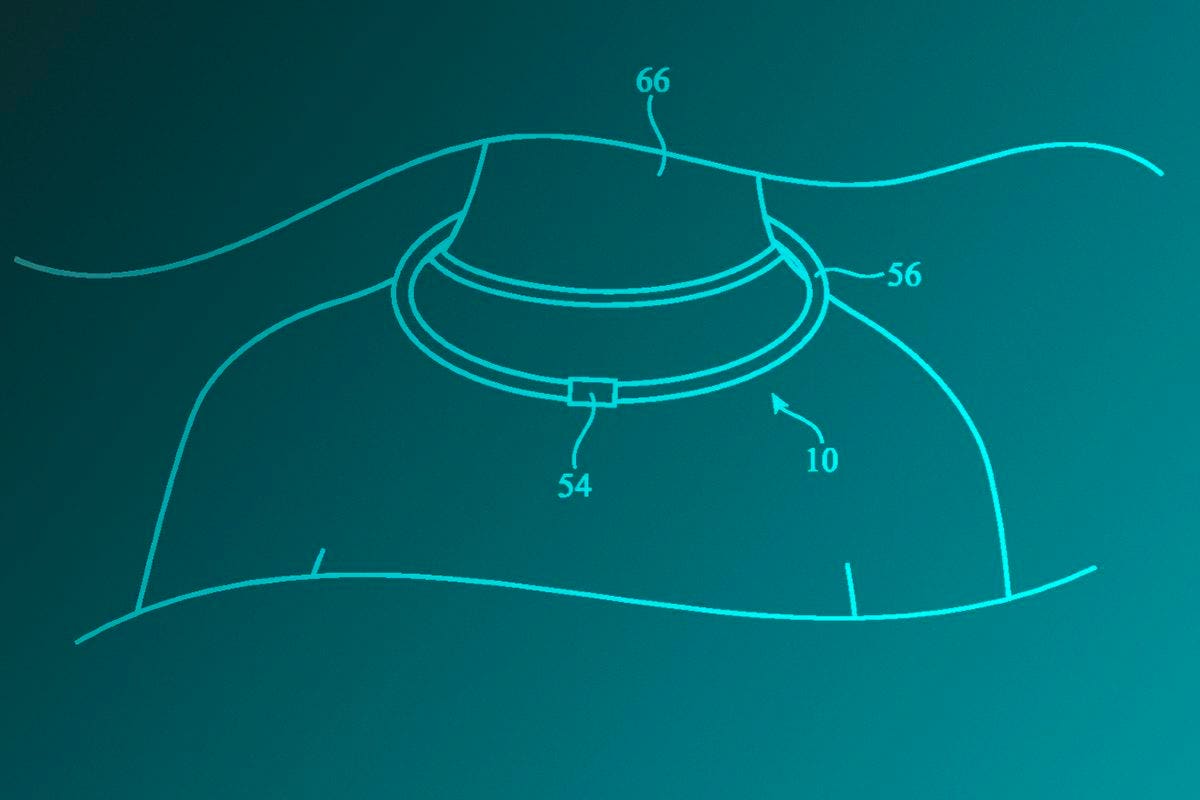

To identify the types of lighting that dominate light pollution in this district of Hong Kong, the team set up a portable spectrometer alongside the all-sky camera and brightness meter. This allowed them to identify the specific wavelengths of light that were decreased or absent during the lights-out period.

They found that emission reductions mostly occurred in three wavelength bands: 445–500nm, 500-540 nm, and 615–650 nm, which corresponds to blue, green and red emissions from LED billboard screens. They also measured reductions in the 585–595 nm range, which is associated with metal halide floodlights used for facades and billboards. The sodium streetlamps had a negligible impact on sky brightening.

They conclude “the substantial darkening observed in Hong Kong [during Earth Hour] can be largely attributed to the simple act of turning off approximately 120 decorative or advertising lights on commercial buildings and shopping malls. Although they represent only a small fraction of the total external lighting in the city…. they are in fact the main contributors to light pollution in Hong Kong.”

The ‘light dome’ of Los Angeles and other major cities can be visible from great distances.

So what?

It’s becoming increasingly clear that excessive or inappropriate use of artificial lighting at night (ALAN) has widespread implications for ecological health. It can confuse and endanger nocturnal species who are active at night. Migratory birds and bats are diverted and disoriented by the presence of artificial lighting on their routes, with many killed as a result of colliding with brightly-lit structures. Other bird species and frogs change their breeding behaviors. A study published last month looked at 7 years of VIIRS data from 428 cities in Northern Hemisphere concluded that artificial light may be lengthening the growing season in urban environments by as much as 3 weeks compared to rural areas.

Humans are also not immune from ALAN’s influence, though it can be challenging to separate it out from that of other environmental factors. Unsurprisingly, it has been shown to disrupt our circadian rhythms (the 24-ish hour cycles that regulate how our bodies function, including our wake-sleep cycle). These disruptions, in turn, have been linked to an elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases, chronic stress, disorders and depression. Chronic, long-term, regular, or cumulative exposure to ALAN may even be a risk factor for certain cancers and neurodegenerative diseases.

Put simply, too much light at night is bad for everyone. And as these (and many other) studies show, most of the light polluting our night skies has nothing to do with safety on our roads and streets. It’s mostly about advertising and poorly mounted floodlights, and to a much lesser extent, people not closing their curtains.

The solutions are relatively simple and numerous. As a start: Avoid lighting up places that don’t actually need to be lit. Where light is needed, be more intentional about what type, how much, and its location. Use timers or motion sensors to enable lights-out periods. Light pollution is serious. Cities need to start treating it as such.