Perched atop the Cerro Pachón mountain in Chile, 8,684 feet high in the Atacama Desert, where the dry air creates some of the best conditions in the world to view the night sky, a new telescope unlike anything built before has begun its survey of the cosmos. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, named for the astronomer who discovered evidence of dark matter in 1978, is expected to reveal some 20 billion galaxies, 17 billion stars in the Milky Way, 10 million supernovas, and millions of smaller objects within the solar system.

“We’re absolutely guaranteed to find something that blows people’s minds,” says Anthony Tyson, chief scientist of the Rubin Observatory. “Something that we cannot tell you, because we don’t know it. Something unusual.”

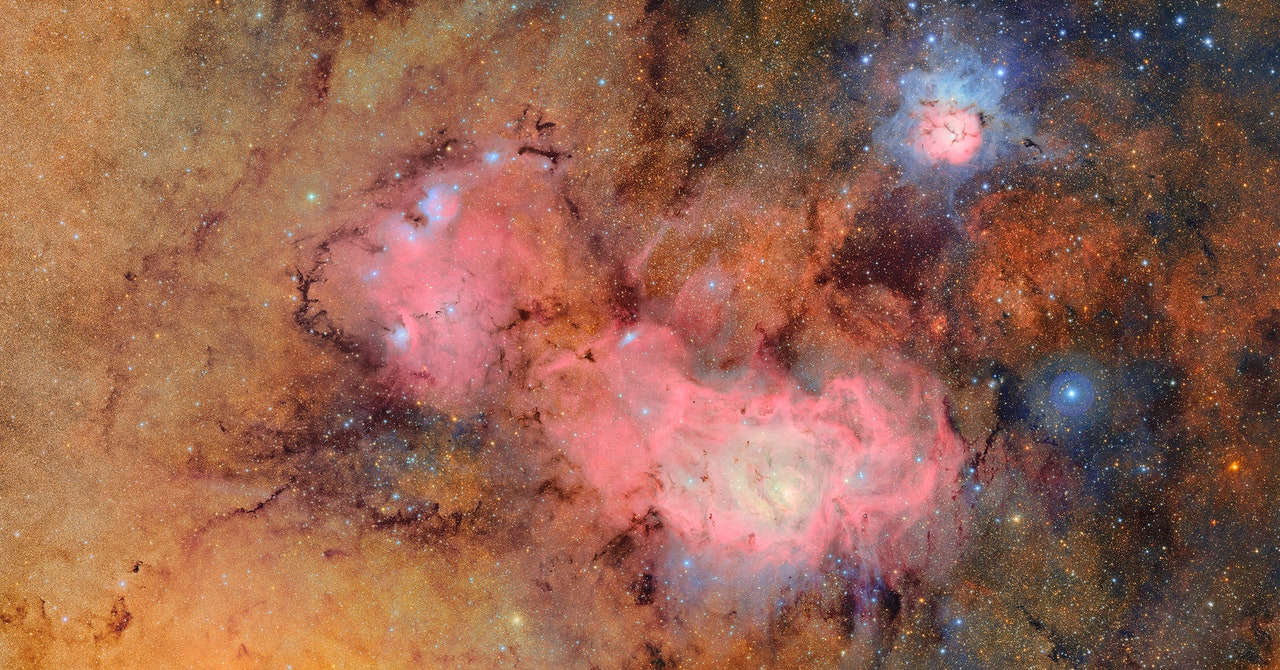

This tremendous astronomical haul will come from the observatory’s 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time, which is slated to begin later this year. The first science images from the telescope were released to the public today.

Rubin’s unprecedented survey of the night sky promises to transform our understanding of the cosmos. What happened during the early stages of planet formation in the solar system? What types of exotic, high-energy explosions occur in the universe? And how does the esoteric force that scientists call dark energy actually work?

“Usually you would design a telescope or a project to go and answer one of these questions,” says Mario Juric, the data management project scientist for Rubin. “What makes Rubin so powerful is that we can build one machine that supplies data to the entire community to solve all of these questions at once.”

The telescope will create a decade-long, high-resolution movie of the universe. It will generate about 20 terabytes of data per day, the equivalent of three years streaming Netflix, piling up some 60,000 terabytes by the end of its survey. In its first year alone, Rubin will compile more data than all previous optical observatories combined.

“You have to have an almost fully automated software suite behind it, because no human can process or even look at these images,” Juric says. “The vast majority of pixels that Rubin is going to collect from the sky will never ever be seen by human eyes, so we have to build software eyes to go through all these images and identify … the most unusual objects.”

Those unusual objects—asteroids from other solar systems, supermassive black holes devouring stars, high-energy blasts with no known source—contain secrets about the workings of the cosmos.

“You build a telescope like this, and it’s the equivalent of building four or five telescopes for specific areas,” Juric says. “But you can do it all at once.”

The observatory on the summit of Cerro Pachón in Chile.NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory/A. Pizarro D.

A Telescope Like No Other

Housed in a 10-story building, the Rubin Observatory is equipped with an 8.4-meter primary mirror and a 3,200-megapixel digital camera, the largest ever built. The telescope rotates on a specialized mount, taking 30-second exposures of the sky before quickly pivoting to a new position. Rubin will take about 1,000 images every night, photographing the entire Southern Hemisphere sky in extraordinary detail every three to four days.

“It’s an amazing piece of engineering,” says Sandrine Thomas, a project scientist who works on the optical instruments of the Rubin Observatory.