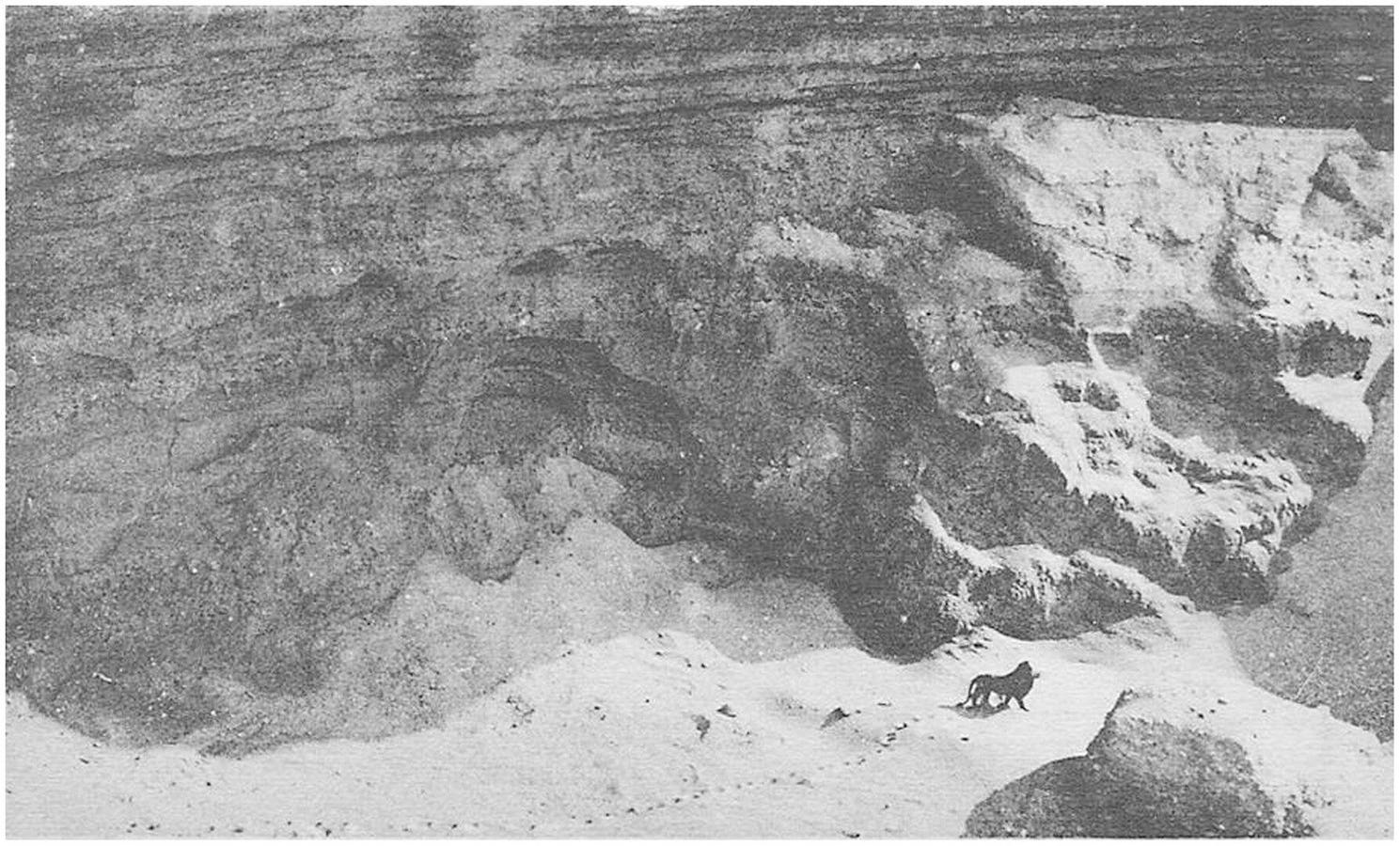

In 1925, a haunting image of a lonely lion wandering the Atlas mountains was captured. Here’s what makes this image so biologically significant.

By Marcelin Flandrin – Black, Simon A. (April 3, 2013) Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69361421

Exactly a century ago, a military photographer (Marcelin Flandrin) documented the end of a legend, completely unknowingly. Captured fleetingly on a flight from Casablanca to Dakar, the black-and-white photograph would become the last known wild photograph of the Barbary lion — one of the most iconic and elusive big cats in history.

Revered and feared in equal measure, the Barbary lion was immortalized in North African folklore as a symbol of power, majesty, and a rapidly vanishing wilderness. As a biologist, however, I see the story of the Barbary lion not only as a cautionary tale of extinction, but also as a sobering lesson in how human expansion can erase the most formidable of creatures.

Here’s what makes this story so interesting.

The Dark-Maned Barbary Lion

A native inhabitant of mountain forests and arid deserts of North Africa exclusively, the alpha cat was nicknamed the “Atlas lion.” Scientists still debate whether the Barbary lion differs enough genetically to warrant its own subspecies designation. What tipped biologists off to its morphological differences was the Barbary lion’s deep golden coat and an anomalous, dark, thick mane.

To the Roman Empire, the Barbary lion was a prized captive. They were hauled from the wilds of Mauritania and brought to gladiator arenas, where they faced off against slaves and soldiers in brutal games. Their image adorned mosaics, sculptures, and shields. In later centuries, Barbary lions were gifted between royal courts, kept in menageries, and even depicted on national emblems — as in the coat of arms of Morocco and the United Kingdom.

But as the centuries progressed, the wild Barbary lion began to vanish.

Hunted To The Brink

By the 1800s, the Ottoman Empire and later European colonial powers had taken control of North Africa. As cities expanded and forests were cleared, the lion’s habitat shrank. But it wasn’t just loss of territory that drove them to extinction — it was sport. European hunters, many of them colonial officers, sought the Barbary lion as a trophy. It was a dangerous, prestigious kill.

Official records from French colonial forces in Algeria report hundreds of lions being shot over the course of the 19th century. Entire regions where lions once thrived became silent.

By the early 20th century, Barbary lions were all but gone from the wild. But it was in 1925 — a century ago — that one final image was taken.

The Last Photograph

The sole hobbyist photographer of a French military unit spots a solitary lion moving through the mist-covered slopes of the Atlas mountains. Stealing a quick break from his reconnaissance mission, he snaps a photograph that, unbeknownst to him, would find a home in the European natural history archive.

A lone Barbary lion wanders into the abyss, as if portending its own extinction.

By Marcelin Flandrin – Black, Simon A. (April 3, 2013) Examining the Extinction of the Barbary Lion and Its Implications for Felid Conservation doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060174, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=69361421

The context of the image underscores its gravity: in an attempt to commit a moment of wild beauty to film, the photographer recorded the last verified sighting of a wild Barbary lion. Not long after, they were declared extinct in the wild.

Ghosts In Captivity

Residues of the Barbary lion gene pool might still be found in captive environments. With the wild Barbary lion wiped out completely, zoos across Europe and North Africa claimed to house “Barbary lions,” but it was unclear whether these lions were pure or mixed with other subspecies.

Some of the lions kept by the Moroccan royal family were thought to be descendants of wild-caught Barbary lions gifted to the sultans generations ago. In the 1990s, genetic testing began to provide answers. Unfortunately, many of the lions bore only partial genetic markers of Barbary ancestry. Crossbreeding in captivity had muddied the waters.

The remaining Barbary lions, if you can even call them such, now find themselves in intense breeding programs in zoos and conservation centers, most notably in Rabat and Addis Ababa. The top priority? To protect and preserve what’s left of the Barbary lion’s unique genetics. The uncertainty around whether we can ever truly restore the subspecies still hangs heavy on conservationists.

A Symbol Of What Was Lost

What does the story of the Barbary lion mean today, a hundred years after that final photograph? For biologists, it’s a painful case study in how easily we can drive a species to extinction, even one that was admired and mythologized.

Our reverence for the Barbary lion falls short of responsibility. We celebrated the Barbary lion in art, heraldry, and literature — but we failed to protect its forests, its prey and its place in the wild.

In conservation circles, the Barbary lion is often invoked as a warning. It reminds us that iconic status doesn’t guarantee survival. Awareness isn’t enough. Without active protection, even the mightiest species can fall.

Does thinking about the extinction of a species instantly change your mood? Take the Connectedness to Nature Scale to see where you stand on this unique personality dimension.