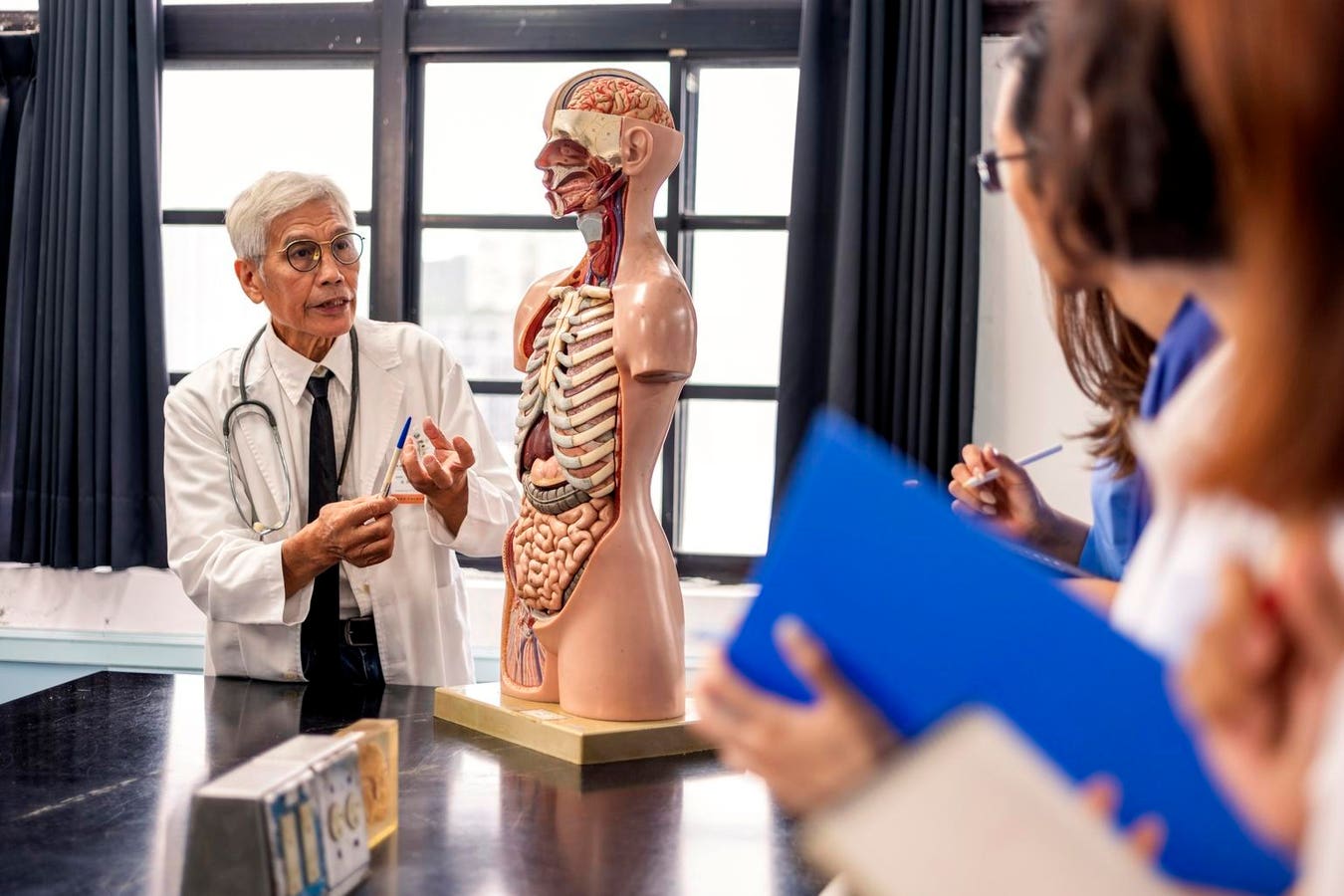

Photo by: Steve De Neef/VW Pics/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The Philippines is one of the world’s hotspots for shark and ray diversity, with approximately 200 species thought to inhabit its waters. Yet most of them are now rare, largely due to overfishing (a problem facing sharks worldwide). Data on population trends here remains limited, and many of the smaller, more threatened species are especially vulnerable because they do not migrate. Instead, they spend their entire lives along the shores of the same island or municipality, concentrating around healthy reefs or seagrass meadows. For these species, medium-sized Marine Protected Areas one of the best long-term solutions for survival.

MPAs are designated sections of the ocean (often including coastlines and estuaries) where human activity is more carefully managed than in surrounding waters to conserve marine life and habitats. Think of it as a kind of national park in the sea. Their effectiveness depends on its size, location, enforcement, and management. A well-enforced, ecologically designed MPA can dramatically increase the abundance of marine life (as seen here). A poorly managed one, however, might exist only “on paper,” offering little real protection. Unfortunately, while the Philippines boasts more than 1,800 designated MPAs — which is nearly 20 percent of the world’s total — the reality is more sobering. Many MPAs were not designed with specific biological criteria in mind, and the vast majority are too small to safeguard species that require even modest amounts of space. The result is a patchwork of underperforming MPAs that have done little to stem declines.

This is why what has just happened in the Philippines matters.

After nearly 18 years of persistence, the Bitaug MPA has officially been designated in the Siquijor province, now standing as the largest MPA in the region. Measuring at149.46 hectares (about 370 acres), this stretch of ocean is more than just a protected zone on a map. Bitaug’s waters are home to coral reefs, lush seagrass meadows, and thriving mangrove habitats. These ecosystems provide shelter for sea turtles, sharks, and countless fish species, many of which are vital to local fisheries; the new protections explicitly prohibit the capture of sharks and rays, except for research purposes. While that may sound like a small rule, it is an important step forward in a country that has historically struggled to protect these species.

This new MPA stands alongside examples like Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, which after 30 years of strong management now hosts some of the largest recorded densities of grey reef and white tip reef sharks in the world. Contrast that with Apo Reef Natural Park, which covers nearly 16,000 hectares with an additional 11,000 hectare buffer zone, but has long struggled with enforcement and governance. Despite those challenges, Apo still manages to support more reef sharks and rays than unprotected sites. Together, these examples show that size matters… but so does management. A well-enforced medium or large MPA can become a sanctuary where shark populations stabilize and begin to recover. “Some of the biggest threats [to sharks]

are direct catch, bycatch, and low enforcement and compliance to existing laws. The new MPA helps address these by creating a ‘safe space’ where sharks cannot be caught and can fulfill their biological needs,” explained Save Philippine Seas Executive Director Anna Oposa via e-mail.

Sharks resting in an overhang in the Philippines.

getty

The new reserve also breaks ground with its management approach, as revenue-sharing from eco-tourism (which includes activities like snorkeling and diving) is built into the framework. That means income generated from the protected area will be reinvested into conservation projects and community development. For a country like the Philippines, where coastal communities often depend on both fishing and tourism, this is a practical way to balance protection with prosperity. And speaking of fishing, central to Bitaug’s success is the Bitaug Fisherfolk Association (BitFA), a local group that has been advocating for this designation for nearly two decades. For fisherfolk, creating a marine protected area can feel like a gamble: closing off areas where they have traditionally fished means short-term sacrifices, but the long-term benefits (i.e. healthier fish populations, more resilient habitats, and sustainable eco-tourism) make those sacrifices worthwhile. BitFA members are not only co-managers of the MPA but also enforcers and educators, ensuring their neighbors understand why this protection matters and how it will benefit future generations. Othello Manos, President of BitFA, described the designation as the culmination of years of hope in a press release: “Hopefully, in time, we will truly take charge of managing and caring for our MPA. This is the beginning of what we’ve been dreaming of for almost eighteen years.”

There are some anticipated challenges, as Anna Oposa points out. “Allocation of and sustaining resources can be a challenge. To operationalize an MPA, the local government will need to ensure continuous patrolling, community engagement, data collection to see social and biological impacts of the MPA, and strict enforcement of the law,” she said in an e-mail. But, there is hope! “SPS in partnership with Marine Wildlife Watch of the Philippines started a new program called Pating Patrol last year, which builds capacity of local champions and government employees to identify sharks and increase their appreciation for the species. This is a possible workshop we could implement in the area with the right support and partnership.”

With mounting threats from climate change, overfishing, and pollution, marine ecosystems are under immense pressure. The Philippines, sitting in the heart of the Coral Triangle, holds some of the richest marine biodiversity in the world. Yet its coastal communities are also among the most vulnerable to climate impacts. Protecting interconnected ecosystems like coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves is not just about saving wildlife — it’s about ensuring food security, storm protection, and livelihoods for people who rely on these waters every day. As Kristine Kate Lim, Country Director for WCS Philippines, put it, “Our coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves are interconnected. They must be protected together if we truly want to secure our environment and our future.”