The story of the fall of the Roman republic involves dysfunctional government, political selfishness, and constitutional collapse, played by the usual actors in togas, famously among them Cicero and Caesar. It also, unexpectedly, offers an overlooked but important lesson about how women’s history affects everyone’s history in ways that deserve to be remembered.

When the first emperor of Rome, Caesar Augustus, rose to power, sweeping away legal norms and enacting the “Law of Three Children,” sometime between 18 B.C. and 9 A.D., the legislation prevented all wealthy, free-born women from claiming their rightful inheritances unless they had given birth three times. Fiercely independent women who had begun to find a voice in public life, thanks to the generous dowries or the estates they inherited, were expected to be mothers and child-bearers first and activists second—if at all.

As the Roman republic’s social and political breakdown quickened, decades of progress in women’s self-determination, emancipation, and participation in public life were erased. The health of the republic suffered because of it.

The Roman republic’s carefully calibrated framework of legislative, judicial, and executive action had long been, in practice, a misogynistic, patriarchal, oligarchical swamp. From its founding in 509 B.C., young men were doted on as promising scions of the house. Girls were given a version of their dad’s name. Colorless adjectives differentiated any female siblings: First, Second, or Third. They were forced to learn about chastity as young girls and fidelity when they matured and became wives. Marriage contracts could be severe, with a man’s legal control extending over his entire household. Roman wives replaced their own family’s name with their husband’s first name, signifying by a quirk of Latin grammar that she “belonged to” him—that is, was “in his possession.”

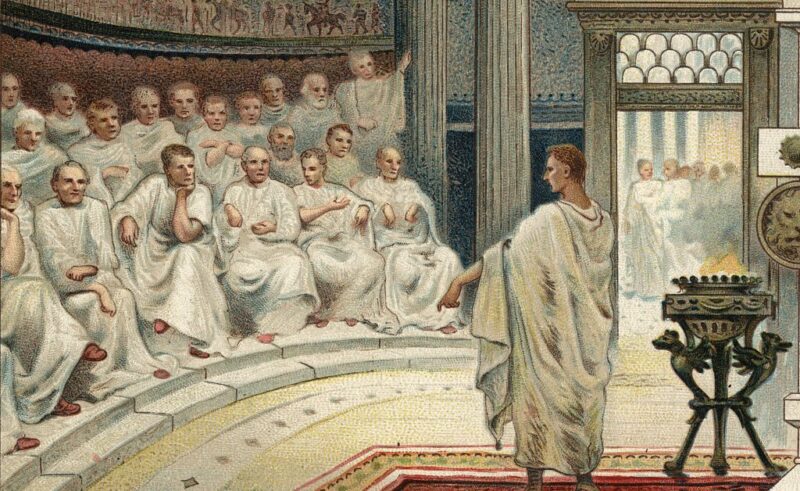

The men of the republic, who called themselves their society’s “Chosen Fathers,” enforced this two-tiered society through strict voting laws and limits on women’s autonomy. Heavily manipulated voting districts ensured that only the voices of the senatorial elite, Rome’s self-proclaimed optimates, or “best men,” dominated, not progressive champions, freed slaves, or newly-enfranchised citizens. No woman could run for higher office. Women could neither sit on juries, nor exercise their vote. “As soon as women become the equals of men,” the statesman and senator Cato the Elder said in 212 B.C., “they will have become our masters.”

Yet as Rome’s republic expanded beyond the capital city, beyond Italy, and gradually acquired its Mediterranean empire, stories of a different sort of woman reset women’s expectations at home. In the eastern Mediterranean, highly educated woman philosophers, avant-garde poets, and above all, the fearless Greek-speaking queens of Egypt, including Cleopatra, held sway. Inspired by these role models across Europe, Africa, and Asia, Roman woman began to challenge the republic’s inequities and ideologies and claim their voices in the male-dominated republic.

Read More: Trump’s Orwellian Erasure of Women

Grandmothers and mothers taught their daughters to read and cultivate their intellectual talents. An educated girl, the new wave of educators argued, knew how to assert herself against a man who “swaggers through the city acting like a tyrant.” Cato’s quotation comes from a pivotal moment when women and their allies poured into the streets to demand the repeal of a war-time-era tax on their savings. Other women were political leaders who earned the scorn of their contemporaries. Some were erased or forgotten. In one case, the life of an upper-class woman and contemporary of Julius Caesar, Clodia, saw her reputation destroyed by false claims of harlotry, home-wrecking, and husband-killing.

Clodia, an unapologetic champion for expanded voting rights for the enfranchised men of Italy, bravely went before an all-male jury in the center of the Roman Forum in April 56 B.C., as the prosecution’s star witness to testify against her day’s runway, endemic corruption. Instead of defending his client from the charges, however, the leading defense attorney, Marcus Tullius Cicero, turned the case into a referendum on Clodia’s character. Transforming Clodia into the trial’s villain, the speech, the Pro Caelio, outlasted Rome’s fall. It has been taught in high school and college classrooms for two millennia as a masterclass of rhetoric, from which countless men in business, law, and politics have learned to emulate Cicero’s misogyny.

Trailblazing women like Clodia have always, in the historian’s shorthand, been called “ahead of their time.” But history deserves to be told from another point of view: by pointing out the parade of men who have stubbornly and perennially thwarted progress. Rome’s republic might have survived a bit longer had its own people listened to, not silenced, its women.

Douglas Boin is Professor of History at Saint Louis University and the author of Clodia of Rome: Champion of the Republic (Norton) which Amazon placed on its list of Best Books of 2025. He lives in Austin with his husband.

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.