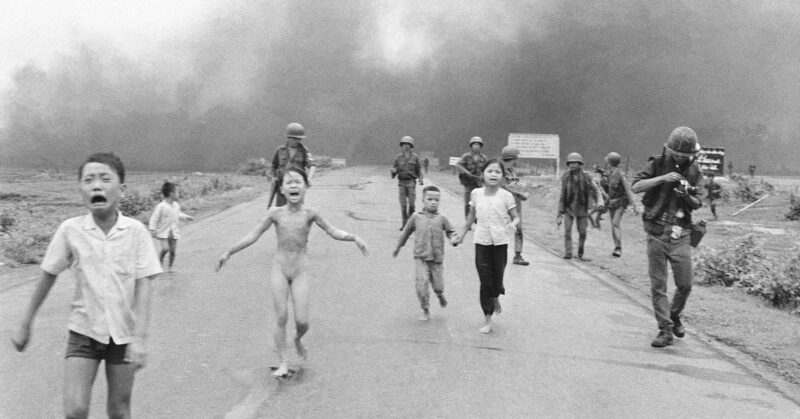

A new documentary raises questions about who really took the Pulitzer Prize-winning 1972 photo of a naked girl and other children screaming and running as they fled a napalm bombing during the Vietnam War.

The credit for the image, titled The Terror of War and known colloquially as the “Napalm Girl” photo, has always gone to the Associated Press staff photographer Nick Ut. The Stringer, out on Netflix Nov. 28, presents another argument. In the documentary, journalists and investigators say that based on news reel footage of the road in Trảng Bàng, where the photo was taken on June 8, 1972, a stringer named Nguyễn Thành Nghệ took the iconic photo of Phan Thị Kim Phúc, not Ut.

“Nick Ut came with me on that assignment but he didn’t take that photo,” Nghệ says in the doc.

The AP is standing by its credit, and Ut did not participate in the documentary. In a statement shared with TIME by his lawyer James Hornstein, Ut said he’s “deeply disappointed that Netflix has chosen to give international distribution to a film whose claims remain unsubstantiated and contested by eyewitnesses and by the historical record.” Hornstein argues “no new documentary evidence — no negative, no contact sheet, no print, no contemporaneous note, and no photographic archive — has surfaced to support an alternative authorship…If credible evidence existed to challenge Nick Út’s authorship, it would not have remained confined to a handful of individuals whose accounts emerge five decades after the fact and contradict the overwhelming body of contemporaneous testimony.”

Yet buzz about the movie hasn’t died down. Here’s how the documentary presents the theory that Ut didn’t take the photo and the reaction it’s gotten so far.

The whistleblower

In Dec. 2022, Carl Robinson, who was an AP photo editor in Vietnam at the time that the photo was taken, reached out to Gary Knight, a photojournalist and Executive Director of the VII Foundation. He wanted Knight to help him share the claim that someone else had taken the photo. “It’s time to clear my conscience,” he says in the doc.

In The Stringer, Robinson recalls examining rolls of film sent from Ut and Nghệ, who showed up to Trảng Bàng independently after learning about the fighting there through media friends. He says that the picture that would become the famous “Napalm Girl” photo was definitely taken by a stringer, as indicated on the roll of film and the log book. There was a photo by Nick Ut that showed the girl running by from a side angle, and that was Robinson’s pick because it was “discreet.” But his supervisor, photojournalist Horst Faas, picked the photo with the full frontal shot because it showed the brutal reality of war. Robinson claims that when he started writing Nghệ’s name, Faas told him to change it to Nick Ut.

Faas’s order has “been with me the rest of my life, those words,” Robinson says in the doc.

When asked why he didn’t correct Faas, Robinson said he was afraid of losing his job because he had three kids. “I always felt bad about that my whole life, that I wasn’t courageous enough.”

More than 50 years since the photo has been taken, Robinson is determined to set the record straight in his lifetime. “I’m going to be 80 years old. Something I really want to do before I pass away is find the real photographer and just say sorry.”

Finding the stringer

Faas died in 2012, so he could not be interviewed for the documentary, but the AP says he would frequently discuss the image publicly and in writings and never doubted that it was Ut’s. However, there have always been rumors in the Vietnamese photography community that Ut did not take the famous photo.

At an event for Vietnamese photographers years ago, Robinson’s Vietnamese wife, who is interviewed in the film, learned that these photographers credit Nghệ with taking the image, and the name always stuck with her because she saw firsthand how upset Robinson was at the time the photo was published.

Robinson and other local Vietnamese journalists discussed their doubts about the official photo credit mainly in private. But in 2023, the theory that Ut didn’t take the photo gained some public traction after Lê Vân, a journalist in Ho Chi Minh City, started posting callouts on Facebook in various photography groups with a photo of Nghệ on the road in Trảng Bàng on June 8, 1972, asking if anyone who knew him could connect her to him. One of Nghệ’s friends saw the post and alerted him, and a few days later, Nghệ called the journalist. His story attracted some buzz on Vietnamese social media, but wasn’t picked up by English-language news outlets.

In the film, Nghệ recounts everything he remembered about the day of the napalm attack in Trảng Bàng and how he took what he thought was “the money shot.” He says he made $20 off the photo, and AP gave him his film back along with a souvenir print of the picture.

But he doesn’t have the print anymore because, he says, his wife was so irate that AP didn’t credit him that she ripped up the print and threw it away. He stopped working as a professional photographer and moved to the U.S. in 1975, where he worked at FotoKem in Burbank, California, developing feature films. A lot of his photography equipment, cameras and negatives that he had in Vietnam were lost because he could only bring one suitcase to the U.S.

The documentary shows the emotional moment when Robinson and Nghệ meet for the first time at a California hospital where Nghệ was recovering from a stroke. “I feel bad that we stole your name,” Robinson tells Nghệ, putting a hand on top of his. “I want to say sorry. You are my proof, and I am your proof.”

Looking back at the moment the photo was taken

The documentary features 3D modeling produced by Index Investigations, which pored over photographs and news reel footage from ITN and NBC of the spot where the photo was taken to recreate who was standing where before and after the camera snapped.

The modeling concludes that 15 seconds after the photograph was taken, Ut was standing 250 feet away.

Based on a photograph of the scene by David Burnett, the modeling shows that for Ut to have taken the photo, he would have needed to run three times the distance traveled by Kim Phuc in three minutes. Burnett declined an interview for the doc.

“Forensic evidence shows that it’s highly improbable that Ut could have been there to take the photo,” the film’s director Bao Nguyen tells TIME, “given the distance that you know was seen in photographs—photographs from the AP—that say that he was standing there much further away than he could have been when he was taking the photo…I want an audience to watch and make up their own mind based on this forensic evidence.”

Reaction to the film

Ut’s lawyer maintains that AP staffers and eyewitnesses from competing news organizations in Trảng Bàng on June 8, 1972, believe Ut took the photo.

In a statement to TIME, Hornstein said, “technical hypotheses cannot substitute for first-hand observation by multiple independent journalists who either saw Nick Ut taking the photograph or reviewed the film with him shortly thereafter.”

He added: “Neither the retrospective testimony introduced in the documentary nor the speculative technical reconstructions it relies upon provide a factual basis to overturn the established record.” Hornstein says he’s reviewing all legal options.

Kim Phúc, the nude girl in the famous picture, did not participate in the documentary, but has said in the past that she believes that Ut took the photo—and that her uncle told her so—though she has no memory of the moment when the photograph was taken.

After doing its own investigation, the AP continues to credit the photo to Ut, arguing there isn’t enough evidence to remove the attribution. It’s open to the possibility that other photographers may have taken the photo, but argues that it’s impossible to know exactly what happened on that road in the village of Trảng Bàng 53 years ago.

World Press Photo also did a forensic investigation and decided to suspend attribution to Ut—though the 1973 “Photo of the Year” award has not been revoked.

Nguyen hopes that the film will empower local photographers in conflict zones worldwide, from Gaza to Ukraine, to speak up if they experienced something similar to what Nghệ experienced:

“My parents were refugees from Vietnam. When they came over to a new country, they just wanted to take care of their family and survive. They didn’t feel like their experience mattered. And so I hope this helps change the mentality that we have towards individuals and understand why people might hold on and live with these secrets quietly for so long because they just never felt like they had the opportunity to speak about it.”

The Stringer gives Nghệ the last word, ending with him sitting outside eating with his daughter and saying, “I was the one who took the photograph. Now I have a voice.”