Anti-pornography crusaders are on a winning streak.

On almost every front, those who argue that pornography is a scourge on society are racking up wins. States are implementing online age verification laws, and some politicians are pursuing aggressive bans on explicit content. Culturally, the viewpoint that porn is not only harmful to women but increasingly men and the sexual development of young people has made significant inroads.

As porn has become more mainstream, so has the discussion around it.

“Porn is bulls—. It is dangerous, not real, and a performance,” pop star Gracie Abrams said in a February interview with Cosmopolitan. “It’s really dangerous for young people for that to be their introduction to sex.”

Once viewed as a fringe moral crusade, the war against porn has ballooned into a multipronged, mainstream force over the past decade that now counts feminists, religious crusaders, alpha male influencers and a growing number of politicians among its ranks. And after several key social and legislative wins, the movement faces its biggest test. A Supreme Court ruling this summer is set to determine whether a Texas law, which mirrors legislation in over a dozen states and requires porn websites to confirm a visitor’s age or face financial penalties in the name of protecting minors from explicit content, infringes on the First Amendment rights of adults.

And it’s not just about age verification. Last month, Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, introduced the Interstate Obscenity Definition Act bill to alter the definition of obscenity under the Communications Act of 1934 and criminalize the transmission across state lines of content deemed obscene. Although the bill has a long, challenging path toward becoming a law, it seeks to label content obscene if it simply focuses on nudity or sex in a way intended to arouse or lacks “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

Free speech advocates and those in the porn industry are concerned.

“It certainly raises alarm bells because this is about more than porn,” Mike Stabile, the public policy director for the Free Speech Coalition, a trade and advocacy organization for the adult entertainment industry, said about the anti-porn legislative momentum. “These are backdoor censorship bills. Porn is the Trojan horse here.”

Many in the adult content world are not entirely against age verification. And while the actual adverse effects of porn remain the subject of intense debate — and growing academic study — it is undeniable that a once fringe and taboo world has become part of the mainstream. One 2023 study found that more people visited the top three porn sites monthly than TikTok, Zoom, Amazon, OpenAI or Netflix. Meanwhile, the rise of OnlyFans has redistributed the money and power of adult content.

But just how “bad” is porn? That, too, remains a heated subject. Rigorous academic and scientific work has done little to turn up definite harms. Still, porn industry leaders have acknowledged their ongoing battle with deepfakes, underage content and revenge porn, including Pornhub, which removed millions of unverified videos from its website in 2020 following allegations that the site showed problematic content.

It’s against that backdrop that many anti-porn crusaders see their movement thriving, in large part as a backlash to just how much porn has evolved from the back rooms of video stores, adult magazines and pay-per-minute phone services.

Gail Dines, a key figure in the anti-porn movement for over 30 years, said the goal isn’t necessarily to ban porn. But if that happens, porn only has itself to blame.

“The porn industry sowed the seeds of its own destruction,” Dines said.

Pre-internet and the porn ‘public health issue’

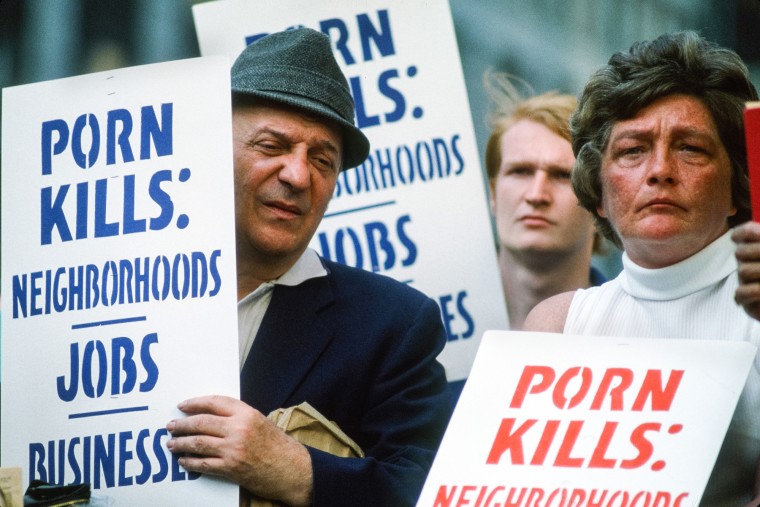

Pornography has quite a history, by some measures dating back thousands of years. And though the anti-pornography movement doesn’t have quite the same track record, its presence in the U.S. has been well documented for decades.

Marty Klein, a certified sex therapist and the author of “America’s War on Sex,” said that the pushback on porn can be traced back to at least the 1950s, when it was primarily coming from religious circles. However, the scope of the issue remained relatively small: Playboy magazine, dirty books and the odd film.

Porn as it might be thought of today took its first steps into the mainstream in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as some adult films saw wider releases. That coincided with the anti-porn movement’s first legal win, when the Supreme Court ruled in 1973 that states were allowed to restrict obscene content based on “community standards.” The ruling came just months after Roe v. Wade was decided.

“Roe v. Wade energized the right … and looked to control the idea of sexuality,” Klein said.

The idea of control, he said, pivoted the fight against porn from a moral issue to a public health one, a move that dovetailed with some feminist critiques. But the work by these feminists, like Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, to create anti-porn legislation (which focused on civil legal remedies for those impacted by the industry and labeling adult entertainment as a women’s civil rights violation) never stuck.

Dines explained that by the 1990s, the third wave of neoliberal feminism took hold, reconceptualizing the movement in the name of empowerment and sexual freedom.

“Instead of it being about exploitation, it became about empowerment and liberation, empowerment and agency, and that this is how women display their sexuality,” Dines said. “This was mainly written by women who were academics who had not had any contact in the porn industry.”

By the early 2000s, the war against porn was most publicly helmed by Focus on the Family and Morality in Media, which launched campaigns to ban adult magazines and prosecute obscenity violations. Those efforts, however, rarely succeeded in court and didn’t make more traction socially as Americans began to see pornography as a private, personal freedom.

The rise of the internet, however, had already begun to make the fight against printed adult content seem quaint. Pornography was suddenly going to be easily accessible to anyone with an internet connection.

The internet, OnlyFans and the new anti-porn wave

Those on both sides of the porn debate agree that the internet changed everything for the adult entertainment industry.

“Pornhub and other free porn sites soon became the wallpaper of boys’ and men’s lives,” Dines said. “It was affordable, accessible and anonymous. You could watch it in your own home.”

Studies about the consumption of pornography vary in their claims, and many have come from interested groups, but it is generally accepted that porn is incredibly common. The digital footprint of porn only grew with the rise of smartphones, laptops and social media. A 2023 Pew Research study found that nearly half of teenagers ages 13 to 17 say they are online “almost constantly,” at a rate that has almost doubled since 2014.

Dines was among the scholars on the front lines against porn, arguing that porn trains young men to dehumanize women and normalizes sexual aggression. This framing was further boosted by campaigns like Fight the New Drug, a nonreligious nonprofit that argues porn is analogous to a drug.

Those ideas have percolated in some corners of the internet for years. With the growing ubiquity of online porn, no-porn subcultures also began to emerge in the name of helping men and confronting the impacts of “centerfold syndrome,” a term coined in the 1990s to explain a fixation on hypersexualized images of women that can lead to a fear of personal inadequacy and difficulty having sexual relationships. Among the loudest advocates against porn in the name of men’s health was Gary Wilson, the author of “Your Brain on Porn” and the founder of a website with the same name.

Wilson, a former teacher who died in 2021, blended neuroscience and anecdotal evidence to argue that porn rewires the brain like a drug. Though criticized by many in the academic community, Wilson’s now-infamous TED talk “The Great Porn Experience” is often cited as laying the groundwork for pro-abstinence, anti-porn internet subcultures.

“With internet porn, a guy can see more hot babes in 10 minutes than his ancestors could see in several lifetimes. The problem is that he has a hunter-gatherer brain. A heavy user’s brain rewires itself to this genetic bonanza,” Wilson said in the TEDx Talk, which has been viewed on YouTube 17 million times.

As technology made finding explicit content as easy as making a phone call and social media allowed sex workers to easily promote their work, anti-porn advocates went on the offensive.

Since 2013, the National Center on Sexual Exploitation has been identifying companies it believes are “major contributors to sexual exploitation” in an annual “Dirty Dozen” list. Four years ago, the organization labeled OnlyFans as “the latest iteration of the online sexual exploitation marketplace” that also “harms minors, and emboldens men to objectify and degrade women.” Apple, Cash App, LinkedIn, Meta and Spotify were listed among the “Dirty Dozen” last year.

This idea — that porn is now hurting men at a significant scale — has been embraced by a variety of right-leaning and anti-woke influencers who have helped push the anti-porn movement beyond conservative circles. Andrew Huberman and Jordan Peterson are among the most high-profile internet personalities who have argued that porn has adverse effects on men.

Questions about the effects of porn on men’s sexual health have also been a hot topic, with some pushing the idea that porn-related masturbation was making men less virile. A 2022 International Journal of Impotence Research study by a group of urologists who studied social media found that “semen retention” and its related hashtags were TikTok’s and Instagram’s most popular men’s health topics. “No Nut” November is now hailed in some circles as an annual holiday challenge.

But does this movement have any scientific backing?

What the science — and the skeptics — say

By 2016, politicians started gaining momentum in the anti-porn movement when Utah became the first state to declare pornography a public health crisis. The resolution, which was not backed by any major health organization, cited personal and social consequences for viewers and the need for policy reform. Two years later, the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE) successfully convinced Walmart to ban Cosmopolitan magazine from its checkout counters.

“We realize this is a bold assertion, and there are some out there who will disagree with us,” then-Utah Gov. Gary Herbert said when he signed the 2016 resolution that called for increased “education, prevention, research, and policy change at the community and societal level” to combat pornography. “We’re here to say it is, in fact, the full-fledged truth.”

For many, the harms of porn are obvious.

Feminists have primarily argued that porn normalizes sexual violence, contributes to the objectification of women and erodes childhood sexual development. Writing in The New York Times, Christine Emba, whose work has focused on gender, sexuality and youth norms, recently pointed to changing sexual habits among young people.

“There are consequences for members of Gen Z, in particular, the first to grow up alongside unlimited and always accessible porn and have their first experiences of sex shaped and mediated by it,” she wrote. “It’s hard not to see a connection between porn-trained behaviors — the choking, slapping and spitting that have become the norm even in early sexual encounters — and young women’s distrust in young men.”

For men, the issue focuses primarily on the idea of an addiction that can ruin their lives, though that also extends to women as well. Chris Rock and Terry Crews have opened up about self-described porn addictions that they say impacted their familial relationships. Billie Eilish called porn a “disgrace” after revealing in a 2021 Howard Stern interview that watching explicit videos when she was 11 “destroyed” her brain and gave her nightmares.

In some parts of the internet, porn’s destructive tendencies are accepted as fact, and the need for rehabilitation obvious. There are all manner of porn addiction recovery resources and online communities dedicated to the issue.

The science, however, remains lacking.

Emily Rothman, a Boston University professor who specializes in public health pornography research, says that while underage youth should not be seeing adult content as easily as they can on today’s internet, false narratives about the impacts of porn have gained traction.

“Evidence supports the contention that pornography — specifically free, online, mainstream pornography — poses a risk to underage youth. But it’s also true that banning pornography altogether has the potential for harm,” Rothman said. “Access to information about sex, sexuality and sexual health is vital for a healthy society, and the power to declare certain media off-limits to everyone in society should be deployed extremely carefully.”

Klein notes that the science behind porn’s alleged harm is not settled, especially because “porn use is generally not separated from internet use or social media use, both of which have harmful effects of their own.”

Studies also show that Americans are not as opposed to porn as the movement suggests. A 2024 Gallup social survey found that only 38% of Americans think that pornography is “morally acceptable,” a slight decrease from 43% in 2018. And a 2023 BYU report found that only 12% of all websites were dedicated to pornography.

“Since porn use is almost universal among men and is consumed by at least a third of women, you can find whatever effects you want, and they’ll be statistically significant because of the huge sample size,” Klein added.

Others have pushed back even more aggressively.

David Ley, a clinical psychologist and the author of “The Myth of Sex Addiction,” explained that there is “not a single study that shows causal changes to the brain from porn,” only a few correlational studies that do not distinguish between existing predispositions and distinct brain differences. According to an NPR article on the online anti-masturbation movement, psychological associations do not recognize a link between erectile dysfunction and masturbation, as these movements claim.

“I call this Valley girl science … the argument by analogy. ‘Porn is like cocaine’ does not mean anything; it doesn’t tell us very much about what is actually going on here,” Ley said.

He noted that while the manosphere is not religious, it is “extremely religious adjacent,” especially when members are talking about how men should perceive themselves and their role in society.

“So when we see Andrew Tate telling young guys that, you know, they’re unmanly, or they’re gay for touching their penis, that creates these insecurities, it creates these values conflicts and this anxiety that then feeds on itself,” Ley added.

“The problem I have with all the anti-porn kind of movements is that they are what I call ‘sexy shiny objects,’ where people get distracted by the sex and the porn, and they try to put a lot of things on that rather than addressing some of the much more significant kinds of issues.”

Whatever one thinks of the debate over porn, the success of the anti-porn movement is clear.

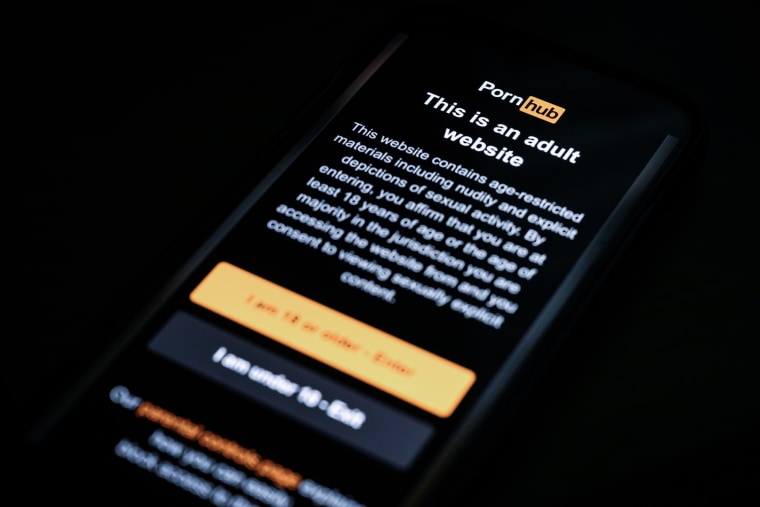

Since 2023, at least 19 Republican states have passed laws requiring websites to confirm a user’s age, either by scanning their face or checking a government-issued ID, before allowing them access to explicit material.

Despite their wins, those leading the anti-porn movement aren’t exactly unified on what victory looks like.

Evangelical conservatives like Russell Vought, a Project 2025 co-author and the White House Office of Management and Budget director, support the outright criminalization of pornography. Feminists like Dines, who believe Lee’s obscenity bill is problematic and wish to move away from the moralistic argument against porn, want the adult industry to be regulated into obsolescence.

“I think Pornhub has realized the time is coming for regulation, and they’re fighting it tooth and nail,” Dines said, adding the success for her is a porn industry so restricted by regulation that it fades from public view.

For porn companies, the fear isn’t reform — but what reform looks like for the loudest voices against the adult entertainment industry. Alex Kekesi, the head of community and brand at Pornhub, said while her company agrees with the spirit of the laws that children should not have access to sexually explicit content, they worry the privacy-invasion laws will only push people toward unsafe, unregulated corners of the internet.

“Having to show your government ID to access something online would make anyone uncomfortable,” Kekesi said. “There are real concerns when it comes to privacy.”

Dines, however, is not too worried about the privacy issue, noting that if users were concerned about privacy, they would not be visiting Pornhub and other adult sites in the first place. For now, though, as the porn industry awaits the Supreme Court decision, its adversaries realize there is a line of sight to winning the war on porn.

“I want to see a shift where pornography isn’t seen as cool,” she said.