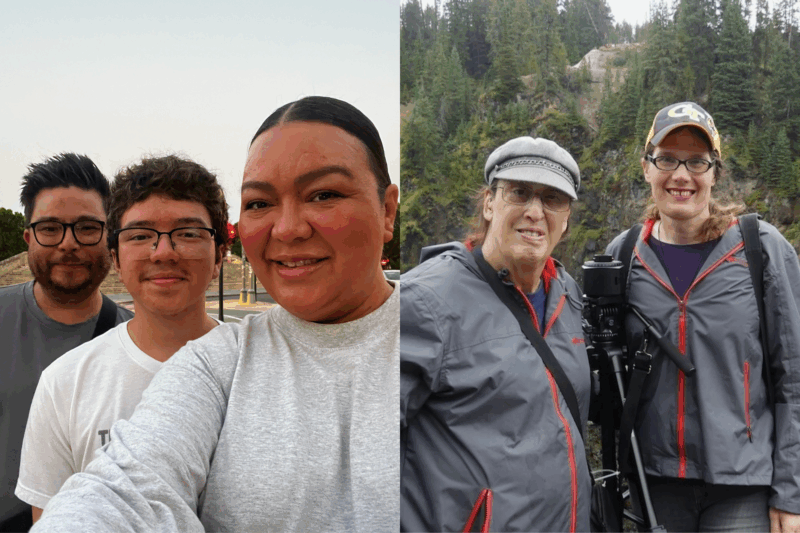

Lizette Trujillo climbs into a taxi two months after she and her family moved abroad with two items in her purse: her U.S. passport and a bottle of Mexican hot sauce.

The latter, a relic of her heritage as the daughter of immigrants, is scarce at the local restaurants in her new home more than 5,000 miles away from the one-story Tucson, Ariz., home she purchased in 2023, not knowing her family would be fleeing the U.S. out of fear for the health and safety of her trans son less than two years later.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

“If you would have asked me in December, would we leave? I would have said no,” Trujillo tells TIME. But seeing President Donald Trump return to the White House and sign an Executive Order that limited access to gender-affirming care for those under the age of 19 just a week into his second term, she says, “made me feel afraid.”

Trujillo and her family are not the only Americans who have left the U.S. amid mounting restrictions on transgender rights. Rainbow Railroad, a global nonprofit that helps LGBTQ+ people escape state-sponsored violence, has received a record-high number of requests for help from U.S. citizens since Trump’s reelection, according to Latoya Nugent, head of engagement at the organization. “That trend has continued,” she says. “The U.S. continues to be the number one country where people are requesting help from,” as of Oct. 6. Around two-thirds of the requests the group has received are from people who are transgender.

The surging efforts to flee from—instead of immigrate to—the U.S. mark a notable break from the past. The country has been regarded as a desired destination for immigrants seeking to escape targeted policies or persecution—including LGBTQ+ people. Now, it’s become a place many trans people, and their families, are trying to leave for the same reason.

The urgency to move elsewhere, Trujillo and others say, is due to the Trump Administration’s anti-trans policies: On his first day back in office, the President signed an Executive Order—which currently faces an injunction but is moving through the courts—recognizing just “two sexes, male and female,” seeking to bar transgender people from updating their gender markers on federal documents. In the following weeks, the Department of Health and Human Services issued a memo discrediting gender-affirming-care—which is supported by every major medical association in the U.S. In July, the Department of Justice issued more than 20 subpoenas to investigate doctors and clinics that provide gender-affirming care to minors.

Republicans have also enacted a raft of policies targeting trans people on the state level in recent years, barring trans and nonbinary people from using the bathroom that corresponds with their gender identity in several states and passing bans on gender-affirming care for minors in more than half the country. The Supreme Court’s conservative majority dealt another blow to transgender rights in June by upholding Tennessee’s state ban. And other potential restrictions loom: More than 600 anti-LGBTQ+ state bills have been introduced in 2025, according to the ACLU’s legislative tracker.

In Arizona, where the Trujillos lived, Republican lawmakers passed 8 anti-LGBTQ+ bills this year, including one that would have barred trans residents from updating their birth certificate to match their gender identity and another, akin to Trump’s Executive Order on sex, that opponents warned would have ended all legal recognition of trans people. While Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs vetoed some of those bills, her term is due to end in January 2027. “What happens in two years if she doesn’t win her reelection?” says Trujillo. “It’s difficult to live like that.”

Experts and advocates have warned that the policy moves could have dire consequences.: Anti-trans policies were linked to a 7-72% increase in suicide attempts by transgender and nonbinary youth, according to a 2024 Trevor Project study published in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

The White House waved off concerns, however. “President Trump is making our country safer, wealthier, and greater than ever before for all Americans,” said White House Assistant Press Secretary Liz Huston in a statement to TIME. “If any person chooses to leave the best country on Earth because of their Trump Derangement Syndrome—that’s their own problem.”

The search for a safe place

Many trans people are moving within the country rather than seeking to leave the U.S. altogether. Nearly half of the transgender adults in the U.S. have relocated or are planning to relocate to another state that they believe to be more affirming to gender-diverse individuals, according to a May report by the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law.

As bans and restrictions have increased, states such as Oregon, Vermont, Connecticut, and Maryland have enacted shield laws to protect patients who cross state lines seeking gender-affirming care—and the health care professionals that provide it—from prosecution in other states. Local leaders are taking protective measures as well. Boston and California’s Long Beach and West Hollywood have all enacted resolutions or ordinances declaring themselves sanctuary cities for transgender people or the broader LGBTQ+ community.

Tucson, where Trujillo is from, has ordinances banning discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. The city earned a full 100 on a 100-point scale for its protections for the LGBTQ+ community, in a 2023 assessment made by the Human Rights Campaign, though there has been variation in its more recent scores due to limitations on trans-inclusive healthcare benefits. Similar discrimination protections exist in 23 states and Washington, D.C.

Despite the comparatively supportive policies in some parts of the U.S., however, Trujillo and a number of others have recently made moves to flee the country entirely, citing fears about a political climate increasingly hostile toward trans people.

Trujillo points to the Children’s Hospital L.A.’s decision to pause gender-affirming-care for trans youth due to Trump Administration threats to cut federal funding. More than 20 hospitals and health systems have similarly rolled back such care since January. “If we would have moved to California, which our family told us to do, we would be in the same space.”

“Those of us who were heavily involved in advocacy had a deep understanding that this is a bigger movement. It has nothing to do with whether you’re in a red state or a blue state, but it has to do with Christian nationalism and lobbies like the Heritage Foundation,” says Trujillo. She and her son Daniel, who is trans, have been advocating against anti-trans policies since he was eight, and were spotlighted by the ACLU’s “Freedom to Be” campaign last year.

The Heritage Foundation, a prominent conservative think tank, drew widespread attention—and criticism—for spearheading Project 2025, a sweeping policy playbook for the next Republican Administration that was published ahead of Trump’s reelection. Among the hundreds of proposals in the agenda were a number targeting trans rights. Trump sought to distance himself from Project 2025 during his campaign, but has moved to enact many of the goals outlined in the project since returning to office.

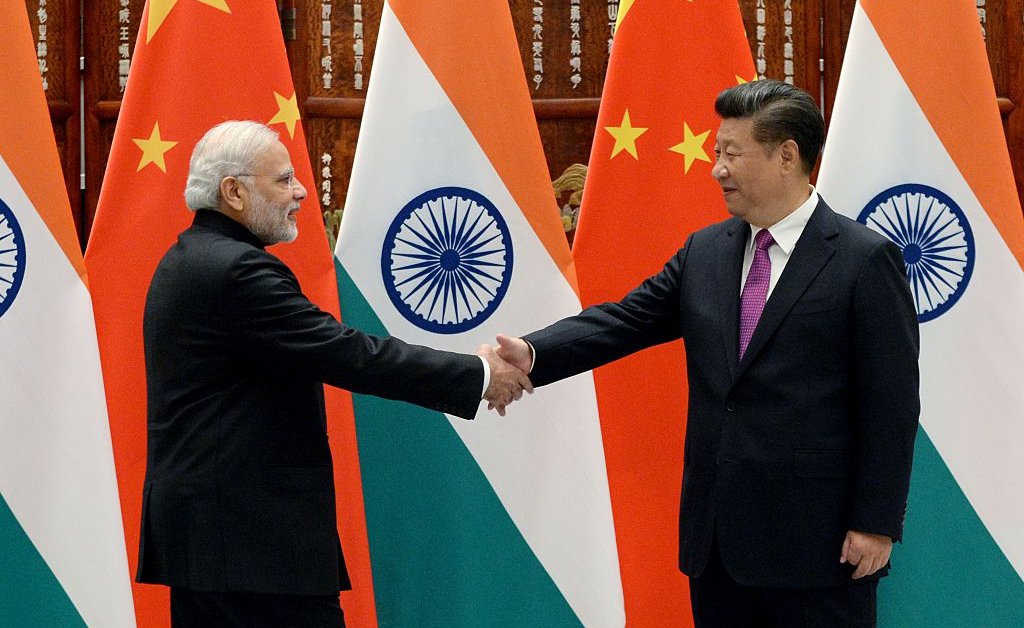

Monica Helms, a 74-year-old transgender veteran and the creator of the transgender flag, moved to Costa Rica from the greater Atlanta area in August because of what she and her wife perceived to be “lack of resistance” shown by blue states in combatting Project 2025.

“We’re not liked by this Administration, and they’re putting out threats to us every day. That makes states feel like they could put out laws that will do damage to us,” says Helms, pointing to a Texas state bill that would have made identifying as transgender a felony. “We’re afraid that other states like ours might want to try to do the same thing. We don’t want to stick around and find out when—if—it becomes too late.”

But moving abroad does not ensure immunity from anti-trans policies, either. The rise of rhetoric and policies targeting trans people in the country reflects a broader trend that extends across national borders and oceans. Shortly following Trujillo’s move to a country heralded as one of the safest in the world for LGBTQ+ people, she says an anti-trans policy was passed in the region.

‘I don’t believe this country cares enough to ever really fix it’

Three nonprofit organizations that work with LGBTQ+ people tell TIME the U.S. was once the premier nation of choice for LGBTQ+ migrants and asylum seekers to aim to resettle in. An estimated 174,200 trans immigrants live in the U.S., according to data from the Williams Institute released last year.

“Up until now, the move has been ‘Come to the U.S. It’s safe and welcoming,’” says Steve Roth, the executive director at the Organization for Refuge, Asylum and Migration (ORAM). “But that has been turned on its head.”

Several people who spoke with TIME about their decisions to leave the U.S. cited not just the mounting restrictions on trans rights, but also broader fears about recent shifts in law and policy.

Trump Administration moves targeting activists sparked concern for the Trujillos, for instance, given their prominence as a trans advocate family. Trujillo pointed to efforts to deport Columbia University student and pro-Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil, as well as the detention of Tufts University doctoral student Rümeysa Öztürk. (The latter was detained due to a 2024 op-ed she co-authored in a student newspaper asking the university president to adopt resolutions that would “acknowledge the Palestinian genocide.”)

“It’s one thing for me to put myself on the line, and it’s another thing to ask my husband and my child to put themselves and their bodies on the line, because while they participate in our advocacy, Daniel didn’t ask to be at the center of that,” Trujillo says.

Debi Jackson, a mother of a trans child and activist who moved from the U.S. to a location that she asked not to disclose for the family’s safety, recalls having to navigate two sets of anti-LGBTQ+ bills for more than a decade while living on the edge of Kansas and Missouri. “We lived on the Missouri side of the state line, but my child was born just across the state line in Kansas. So when Missouri had minimal protections, we were stuck with Kansas and our inability to update our child’s birth certificate there. And when we had a Democrat governor, and things look better on the Kansas side, Missouri started getting more and more deeply red,” she recounts. “With the next legislative session or two, and with the way that they were talking about things on the national level, [and] Fox News’s obsession with hundreds of anti-trans stories, we knew where it was going to go,” Jackson adds.

But she points to the overturning of Roe v. Wade and the mass shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, both of which occurred in 2022, as the final push to move elsewhere. “Both the kids said: why are we here? I don’t believe this country cares enough to ever really fix it [things], and they’re going to keep coming for us,” Jackson says.

That same year, Rainbow Railroad said the U.S. ranked in the top ten countries people were sending requests for help from, for the first time in their organization’s nearly two-decade history.

Today, the U.S. tops the list.

And it’s not just LGBTQ+ people and their families who are looking to move abroad.

More than 1,900 U.S. citizens applied for a U.K. passport during the first quarter of 2025—the highest level recorded since the office started keeping track in 2004. Ireland and Canada have similarly recorded rises in Americans looking to become citizens since January.

A similar trend was seen—though not to the same extent—during the first Trump Administration, when asylum claims filed by U.S. citizens rose, according to research by American University Washington College of Law Professor Jayesh Rathod.

The road ahead

Nearly two years after Jackson and her family sold all of their belongings—including their house and car—their move abroad has offered them the safety and happiness they longed for in the U.S. Jackson says she is now in a place where families are turning to her for support and guidance on how to leave. “Immigrating isn’t easy. You have to have a certain kind of job that they need, or you have to have so many dollars that you can live on. You can’t move and then find a job. You have to have been given a job offer, and then have the company sponsor you,” she says. “I don’t have a good gauge of how many families actually are moving. I just know that there are hundreds who are in discussion in private spaces all the time about, ‘Where can we go? What visa can we apply for? How did you do it? How much should we have?’”

Fewer than 400, or 3%, of asylum claims filed by U.S. citizens from 2000 to 2021 were granted. For LGBTQ+ asylum seekers in particular, experts note, the variation between states’ policies have presented an obstacle for efforts to leave the U.S.

“Because the U.S. is such a large country and there are some states that are still considered safe for LGBTQ people, it’s difficult for U.S. citizens to prove to an immigration judge that it’s impossible for them to relocate to another part of the U.S.,” says Nugent, of Rainbow Railroad.

It might be easier for some people to pursue asylum applications in the future, if other countries move to recognize that the U.S. may be becoming less safe for trans people. A recent court ruling in neighboring Canada signaled a potential shift in that direction: In July, a federal judge in the country blocked the deportation of a nonbinary person to the U.S., citing the “current conditions for LGBTQ, non-binary and transgender persons.”

But countries may be hesitant to take the step of granting Americans asylum. Rathod notes that the potential geopolitical repercussions of declaring that a particular person or group is unsafe in the U.S. would likely weigh on countries deciding whether to take that step. “If you grant a U.S. citizen asylum, it’s signaling to the world that the U.S. is unsafe, or that it can’t protect its people, or that it’s harming its own people,” he says. “That’s not a message that many countries, particularly developed, industrialized countries like the United States like.”

Regardless, some families aren’t willing to wait on a hypothetical future in which their asylum claims would be approved before they move, believing their safety is already at risk.

However, even if they feel leaving is necessary it can still feel emotionally heavy. Trujillo’s son initially pushed back against his family’s decision to flee the U.S. in April, which forced him to miss out on prom and put an end to his dreams of attending Berklee College of Music. “It came at a price to him,” she says. But he “also understood instinctually that it was time to remove ourselves for a bit.”

Six months into their move abroad, Trujillo still refers to the U.S. as home. Mementos and reminders of family are scattered among her belongings: Hanging on the coat rack in the corner of the family’s long-term rental is her father’s old hay-colored cowboy hat, smudged with sweat stains from years of wear and tear. Sitting on the counter are the chile candies she and her husband ration for the moments when they are missing home.

“Sometimes,” she tells TIME in June, “I wake up and I think, ‘Oh, when is this nightmare going to be over so that we can go back home? Will we be able to go back home?’”